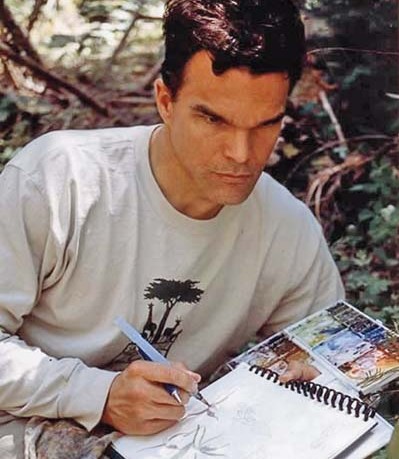

It’s always a red-letter day at the Bay Nature office when we get a visit from Jack Laws (aka John Muir Laws, wildlife artist extraordinaire and the man behind the Naturalist’s Notebook in the back of every issue of Bay Nature). Jack was here to drop off his October page (stay tuned for the fight of the century! Stilt vs. Avocet — get your tickets now). He was also recently featured in the SF Chronicle — check it out.

But what made this visit special was hearing about his new book, The Laws Guide to Drawing Birds. It’s always a delight to hear Jack talk about how drawing can really heighten our awareness of the natural world and key us into to so many things about animals, plants, and ourselves too.

“What I was really trying to do was to deconstruct the process I’m going through when I am drawing and sketching in the field,” said Jack. “When I am looking at a bird how do I simplify the bird so I can get the basic masses and forms and why do I do it in that order? This made me really articulate what it is I am doing and why I am doing it. That helped me see where I wasn’t paying attention, so the process of making this book made me a better artist. Let’s say a bird has some curves on its chest – you get so involved into making that circle, you lose the actual shape. You over-round everything. So I became much more intentional about getting those angles first.”

That kind of careful observation improves any kind of drawing. But there’s a lot to learn about birds and other animals as well. Jack’s book has all kinds of pointers about why birds work in certain ways — how their feathers work or the shape of their bodies beneath the feathers and their skeletons at the core.

“There’s some basic bird anatomy that bird artists should have under their belt,” he says. “If you have that, you can rotate the bird in any angle, and it makes it much easier to draw from memory. When I am seeing the bird, there are just a couple of things I need to key in on. I can get these details, and if the bird flies off, I can now draw that wing without starting from nothing.”

Jack even explained a bit of how our own eyes work — and how the primary colors you learned in elementary school aren’t the right ones. Here at Bay Nature, we know a bit about that. Every color you see in the magazine is some combination of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. Those first three, “CMY”, are the real primary colors for us, for Jack, and, he says, for everybody.

“I was out in the middle of the California desert trying to draw a magenta flower and I was diluting red and it just didn’t turn pink,” he explains. Finally, he discovered that he was simply using the wrong primary colors (read more on Jack’s blog). “It has to do with the way our eyes work with our three kinds of cones [in our retinas], as opposed to the four that birds have or the 16 that mantis shrimp have. If you had bird vision, you would actually see ultraviolet. We really can’t imagine what that world would look like, and, well the mantis shrimp is just off the hook!” (Thanks to RadioLab for that last bit on shrimp!)

And if you really want to see Jack in action, here’s his impression of how a male avocet scares an approaching predator away from its nest:

Jack’s daughter was nowhere in sight, but we were distracted!