Saturday morning, an odd sort of earthquake occurred in Hayward — it came from the surface rather than the depths.

The seismically unsafe 13-story Warren Hall at California State University East Bay (CSUEB) imploded in what the United States Geological Survey (USGS) referred to as a “free” seismic source, a manmade earthquake that caused no unintended damage but that can be used to deepen our understanding of the Hayward Fault, that chthonic monster whose danger was responsible for the building’s preemptive demolition in the first place.

CSUEB’s geology department initiated the East Bay Seismic Experiment when it recognized the implosion as a great opportunity and contacted the USGS in Menlo Park with the idea of treating it as something rarely seen: a predictable earthquake. Scientists set about to carpet the area with temporary sensors, installing more than 500 around the makeshift epicenter. They were placed anywhere from vacant lots to people’s front yards and were primed to detect the controlled earthquake. The information the sensors collected will be used to further investigate the nearby area of the Hayward Fault, which is overdue for a large quake.

The implosion – as would an earthquake – sent waves radiating through the earth, which will allow geologists to map the local section of the fault. The waves act much like sonar, constructing a picture of what lies beneath. They change their behavior depending on the material through which they are traveling, with high-density materials transmitting waves more quickly than low density ones. Because the atoms in high-density materials are closer together, they can transmit the energy more quickly. In this case, faster waves indicate solid, more stable bedrock, while slower ones indicate loose sediment, which is more unstable and more prone to intense shaking. Geologists can get a sense of the subsurface structure based on when the waves arrived at the various sensors. This could allow scientists to predict which areas of Hayward will be most subject to violent shaking in the next large earthquake.

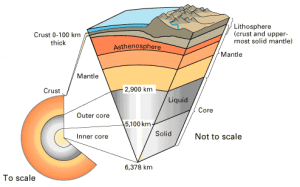

This method of using waves as a window into what can’t be seen is not new; in fact, geologists used it to discover the crust-mantle-outer core-inner core model of the Earth’s interior that placed Journey to the Center of the Earth firmly in the realm of fiction. Now the method is expected to allow scientists to determine not only the underlying materials but the structure of the fault itself, including whether or not it connects to parallel faults. Because a fault typically separates different rock or soil types or contains a thin layer of distinct material – often clay or ground-up rock formed as the two fault blocks scoured each other – waves can change paths or speeds in the fault zone as they move through the anomalous layer. This wave behavior should cause the buried fault zone to light up in the results.

Not only should the experiment allow scientists to map part of the Hayward Fault, it could also help make the Bay Area’s regional earthquake-monitoring network more accurate. Scientists will look into how well the network pinpointed the implosion and – if necessary – will adjust the regional seismic network to improve its performance for the future.

It may come as a surprise that our knowledge of this notorious fault is limited, but this attests to the unique nature of the experiment. Implosions for research purposes are far too costly, but in this case the necessary factors fell into place perfectly. A building adjacent to the Hayward Fault was in need of demolition and conveniently located on a college campus where geologists would notice it. The threat of an earthquake brought Warren Hall to the ground, but hopefully the building’s sacrifice will diminish that threat, helping us prepare for the temblor that cannot be controlled.

Claire Mathieson is a Bay Nature editorial intern.