In 2013, in the midst of the worst drought in California history, a Whittier-based computer repairman named Nicholas Gumina decided he needed to take drastic action in his garden. Out went the tomatoes, the lemon balm, and the jalapeños. In their place he planted cactuses. Nothing but cactuses.

Gumina had always been interested in the weather, since he was a little kid growing up in much wetter 1990s California. He loves to talk about it with other people, to analyze forecasts and atmospheric dynamics and ocean trends. Over the last decade he has left thousands of comments on the blog Weather West, the go-to forum for California weather enthusiasts. After his garden makeover, he logged on to the blog to announce a change of screenname to match the change of plants. “Lightning10,” his original nom de plume, needed something for the age of the megadrought. Now he shares his weather gloom daily as the Fair Weather Cactus.

“I’m probably the most hated person on that board,” Gumina told me by phone. “I was ahead of the curve.”

The Weather West comments — and, Gumina and many others would argue, the skies themselves — have taken a dark turn of late. Or, in the case of the sky, not dark turn, and that’s the whole problem. An exceptionally dry fall has descended on Northern California again. There’s no rain in the forecast and predictions say it’ll be a drier-than-normal November. The discussion among commenters on the weather blog this fall has become a peculiar window into the daily emotional toll of drought and climate anxiety.

To understand the pessimism, panicky GIFs, and dark humor, you need to understand first that when it comes to weather there are basically two kinds of Californians. There are people who say they like it here because of the weather. Of course what they really like is what meteorological enthusiasts might call the absence of weather — the certainty that the vast majority of dawns will bring clear skies and warm temperatures. Then there are the people who live here but desperately love weather. The kind who take vacations to see clouds, who set alarms to wake up in the middle of the night to catch a hailstorm, who drive out into blinding rain because there’s a chance of lightning, who grind their teeth when people remark on the “nice” sunny weather in January.

“I absolutely love when it rains,” says Alex Neigher, a San Francisco software engineer and former meteorologist who’s lurked on Weather West since its creation. “I am that person who will go outside and close my eyes and stick my tongue out. It feels like the earth is taking a deep breath and drinking from the water.”

“We live in California, we don’t get enough weather, and we’re all weather nerds,” says Tyler Price, a generally optimistic Weather West commenter who works in a restaurant in Seaside. “Rain is weather.”

Craig Heden, a mainstay of the Weather West comment section, was born in San Francisco on a tempestuously rainy day in 1951. He thinks he somehow picked up his interest in the weather right then and there. It’s been a love affair ever since. He’s spent so much time staring at the sky he says he’s developed a sort of spidey sense for the subtle meanings of cloud formations, bird migrations, and wind. After a career in the Bay Area in semiconductor manufacturing, Heden retired to Cottonwood, near Red Bluff, to be somewhere with more interesting weather. He spends two or three hours every morning looking over the various forecasts, analyzing them against his own study of the sky. Then he goes over to Weather West to write up a synthesis of what the two are telling him.

Many of the amateur meteorologists you’ll find on Weather West do the same, and refer to themselves as “model riders.” Every day, roughly every six hours, the official weather services of the world run sophisticated computer models and release new two-week forecasts. With each update the model riders flock to the comments section to discuss what they see. A rainy forecast leads to excitement. Disappointment over a bad model run or two leads quickly to despair.

“In the 2015-2016 El Nino, there were weeks after weeks in winter where it would show storms 200-300 hours out — not just one storm but a storm train — and then as we get closer … it would disappear,” Price says. “That was the trend for that year. All the monthly models, the Climate Prediction Center and everything, would predict a wet month for the next month and then it would go to dry the last couple days [before rain arrived]. The models would just keep taking away rain as it got closer. It was really frustrating to anyone model riding that year.”

As Northern California transitions from warm, sunny October days to warm, sunny November days, it is the season of the model rider’s discontent. It is the season when perhaps conceivably our first winter-like storm might arrive, and the model rider’s most earnest desire is to see the storm move from forecast to fruition. Right now it is a desire thwarted. Storms do not appear on the horizon. Or storms appear two weeks out, and then disappear from the models as the date draws closer. By bad luck, and also by climate change, the storm watchers grow frustrated. Slowly, over the course of a dry year in California, as storm after storm fails to materialize, the model riding anxiety, and emotion build.

Medium-range forecast models aren’t perfect. The farther out they go in time, or the more they try to zoom in, the less perfect they become. The model riders call the window two to three weeks out “fantasyland.” When a storm shows up in fantasyland, they hope that it will keep showing up all the way into the one-week window, when the chances are much better it will, as they say, “verify.” The dark strain of pessimism, frequently expressed, is that if fantasyland says it will be dry, it will be dry. If fantasyland says it will rain, it will be dry.

“The best way to describe it, it’s like rooting for a bad team,” Gumina says. “A team like the Detroit Lions, you know they’re going to lose but you’re still a fan. You’ve just grown up and you’re expecting them to lose, but you’re finding new and creative ways to lose. How’s this storm going to bust today?”

Gumina and other Weather West model riders frequently post old Peanuts cartoons of Lucy pulling the football away from Charlie Brown just before he kicks it. The analogy is apt — the models giveth, and the models taketh. But mostly taketh. Probably because the rewards come so unpredictably, the riders stay hooked on fantasyland.

Tracking the forecast too closely in the fall, a difficult-to-forecast shoulder season, can be especially hazardous to the emotions. October is one of the first months when it’s reasonable a storm might land in California; it’s also a month when it’s not unprecedented to have no rain at all. And although there’s no clear link between October rainfall and the rest of the winter, it feels like a sign. Particularly as we move into November when rain is normal.

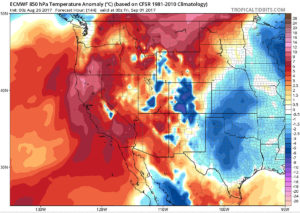

Climate change also seems to be shifting the arrival of winter storms. Fall is getting warmer and drier in California. We’ve already had a dry spring. And as we found out in the 2012-2016 drought, our hemisphere-scale weather patterns are becoming more persistent, and the models seem to have extra trouble with the physics of the new regime. When something appears like the “ridiculously resilient ridge,” a term coined by Weather West’s creator Daniel Swain to describe the storm-blocking pattern that persisted for months in the winters of 2013-2015, the models seem to think it should go away even when it has no intention of doing so. The model riders suffer accordingly: storms rage and dump in fantasyland, and in real-life-land we just sit and wait and watch the sun go round.

The mirage has reoccured this fall. By late September, the models showed storms two weeks out. The storms have remained two weeks out. They were still, near the end of October, two weeks out. Then around the last week of October, they disappeared from even fantasyland.

The more optimistic model riders try to remind each other that a dry October doesn’t mean a dry winter, a dry November doesn’t mean a dry December.

The pessimists freely remind everyone that it’s dry until that first storm arrives and as long as this pattern persists maybe the rain just never will.

“Sometimes the pessimism, we’re toying with it but there’s an element of truth behind it,” Heden says. “The general contributor to the blog, their lives are more connected to the environment than a general layperson. When the guys are going out there and planning their vacations around whether the environment will be good, is the weather good, will I have snow — to pay attention to that, all you’re doing is celebrating life. You’re doing that by going out and experiencing it. If for some reason you feel like that’s being taken away from you, that’s where the emotion comes in. People are not willing to have green forests, water in the rivers, fish taken away from them.”

It does feel, when you see that new model come out with no sign of the storms it had predicted on the previous run, like something has been taken from you. But of course we understand it hasn’t. The Pacific does not owe us rain. The computer does not have the power to manifest in real life what it projects in its virtual future. Living in fantasyland is just like any other form of entertainment: a ride.

“It certainly helps to fill the time for an old retired fart like me,” Heden says. “The fishing is crappy, I’m out of scotch and my car doesn’t run too well.”

California gets most of its rain from a handful of winter storms. That means that any single day really is more likely to be dry than wet. If dry weather makes you unhappy, you are going to be unhappy in California most of the time.

“I think people who look in fantasyland for hints of precipitation that will help us, they’re torturing themselves,” says Arjun Mukerji, a graduate student in cognitive neuroscience at UC Berkeley who’s been a regular on Weather West since he moved here in 2014. “There’s an element of masochism. I just think, there are so many factors that line up to cause us to have a better than 50 percent chance of dry weather. If you say dry and sunny, you’ll be right more than 50 percent of the time. That’s how it is here.”

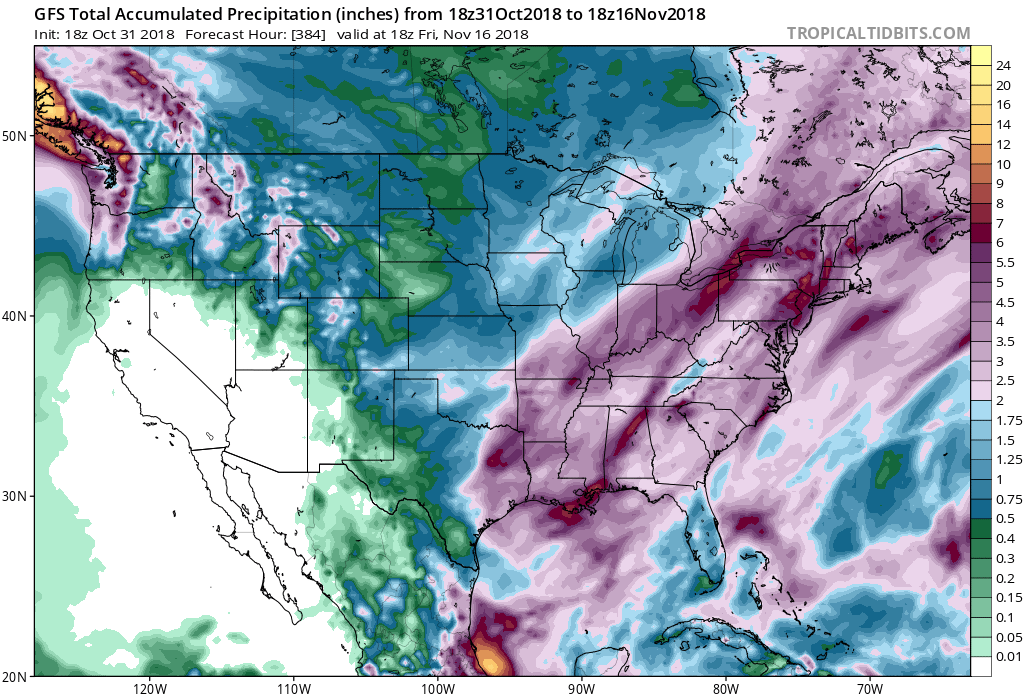

Most riders follow three main models: the GFS, or Global Forecast System, run by the United States National Centers for Environmental Prediction, the ECMWF or Euro, run by the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts in the United Kingdom, and the GEM, or Global Environmental Multiscale Model, run by the Canadian Weather Service. Each model runs numerically, meaning it takes all the data collected from satellites and weather stations and buoys and performs a whole lot of advanced math to try and predict what will happen. Each service publishes both an “operational” model that’s meant to give the finest-grained look possible, and an “ensemble” that averages several dozen bigger-picture model runs.

It rained briefly in Central and Northern California on October 1, 2018, then went completely dry for the rest of the month. On October 29, the GFS operational model forecast no rain in the Bay Area through the limit of its vision — out to November 14.

Still, says Open Snow Tahoe forecaster Bryan Allegretto, it’s not time to panic — yet. Allegretto has worked for the last 12 years as more or less a professional model rider. His job is to look through the various model outputs, and look at what’s happening in the ocean, and synthesize it all in a way that’s useful to people who need to know if or when it will snow. Allegretto might have coined the “model rider” term — some say he did; he’s not certain, though it wouldn’t be out of character — and he says he can sympathize. It’s frustrating if you think it will snow and then it doesn’t. It’s disappointing when a storm shows up in one model and not in another. But it’s also not productive getting too upset about it. Models flip and flop. Patience matters.

“I try, professionally, on purpose, not to get people emotional,” he told me. “Not do to them what the models do to us. I try to average it out, show why the models might be right or wrong. I’m kind of the counselor I guess.”

Allegretto says it’s too early to be riding models in October. Once November rolls around, he says, you can start looking more closely. No snow by Thanksgiving is when you get nervous. No snow by Christmas is when it’s a real problem. Allegretto wrote a post at Open Snow on October 25 about how to ride the models without letting too much emotion creep in. He described his own process, and used it to work out the early November forecast. The main thing, he says, is just not to get too attached to a single run of the operational models.

“If you ran them yesterday and the GFS is showing dry for two weeks, why are you waking up as fast as you can to see if it shows storms two weeks out?” he said. “First of all, you don’t believe that [forecast], so you’re going to have anxiety for 14 days waiting for the storm to get there and make sure it shows up. We see a storm — OK, it’s still there, it’s still there, it’s still there. Fourteen days? Four times a day? That’s, let’s see, 14 times four is 56 times, waiting to be sure the storm makes it to your house! You’re going to take years off your life.”

I want to confess now that I, too, have become something of a model rider. While I don’t look at the models themselves, I tend to head over to Weather West once or twice a day to judge the probability of rain by the tenor of the comments. And what I have come to realize is that I am basically in the bargaining stage of climate grief. I am unrelentingly anxious about climate change; cool weather and rain relieves my anxiety. There’s just enough uncertainty in the near-term about the exact details of how this plays out to hope for good luck. After all the near-certainty of catastrophic megadrought in the future doesn’t mean the megadrought has to start this winter. The likelihood of a drier than normal winter doesn’t mean this week has to be dry.

It is, as more than a few model riders pointed out, very much the same as playing the slot machines. We all know the house wins in the long run. But sometimes in the moment you get lucky. Every so often you ride that beautiful Gulf of Alaska storm for 384 hours until it lands.

“When it’s snowing no one is talking about climate,” Allegretto says. “They don’t start talking about it until a lack of snow. Then it gets bleak and all the conversations switch to climate.”

Every six hours the models come out with this little window into the future, this little sliver of hope, this promise that for at least the next six hours you can hope not to confront reality. Every once in a while the universe offers mercy. Rain, or the promise of rain, feels like a benediction.