No whale watch boat captain worth his or her salt is going to guarantee a whale sighting on any particular trip. But Captain Joe Nazar and the rest of the San Francisco Whale Tours crew on the good ship Kitty Kat had sighted several humpback whales off the Marin coast during their first morning cruise from Pier 39 on this overcast September day. And so there was no reason to think we’d come up empty a few hours later on the mid-day cruise. Especially given the impressive roster of whale expertise assembled for this particular trip, a group that included Captain Joe, an eight-year veteran of these cruises; two of the company’s marine science naturalist guides, Sydney Minges and Allison Payne; and Bill Keener, co-founder and senior scientist with Golden Gate Cetacean Research (GGCR). Over the past three years, GGCR has been documenting and analyzing the surprising presence of humpbacks inside San Francisco Bay, a study greatly assisted by the folks at SF Whale Tours, who probably encounter more humpbacks than anyone else in the Bay Area, with their thrice-daily whale watch trips from March through October. If there were any whales out there, we should be able to find them.

While there is a certain amount of luck involved in finding any marine animal in a very large body of water (after all, they spend most of their time under the water), there’s also a large dose of science and experience involved. Because even though whales can be playful and engage in behaviors that aren’t strictly about survival, their movements aren’t random. And in particular during the non-breeding season for humpbacks — the time of year when they are found off the coast of California and Oregon — their movements are dictated primarily by the availability of prey. Or, as Keener puts it so succinctly, “It’s all about the food.” If you can find out where the food is, you can probably find the whales.

I had contacted Keener several months earlier, in late April, after catching sight of two humpbacks spouting and diving in the deep Bay waters between Yellow Bluff (in Sausalito) and Angel Island. I knew that humpbacks had been sighted regularly in San Francisco Bay the previous two years during the spring and summer and yet had failed in several attempts to see them myself from Cavallo Point (at Fort Baker in Sausalito). After all, whales don’t appear on command.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Golden Gate Cetacean Research has just launched a “Golden Gate Cetacean Watch” Facebook page that provides regular updates on whale, dolphin and porpoise sightings inside and outside San Francisco Bay. To report whale sightings in the Bay, go to the GGCR website: ggcetacean.org.

San Francisco Whale Tours runs regularly scheduled whale watching trips throughout the year, focusing on humpbacks from late spring through mid-fall, and then shifting to gray whales during the winter and spring migration seasons. For more information go to sanfranciscowhaletours.com

In April 2018 I was out at Fort Baker and thought I’d give the whales another chance. I sat out on the cliff, bundled up against the cold wind blowing through the Gate, scanning the water for more than half an hour. I was getting ready to give it up when I saw what looked like a spout, or rather two spouts, in the distance, in front of Angel Island. The general pattern is for the whales to come to the surface to breathe—first sending up the spout of water (their exhalation), followed by the back and the dorsal fin—several times in succession over the course of a minute or two or three, before they show their tails and go down for a deeper dive. Once they’ve gone down, it can be a challenge to find them again, because they probably won’t reappear in the same spot. But on this day, I was rewarded with several good returns in the same general area, each time ending with that slow raising of the tail out of the water, like a banner saying “see you later!” as the mammoth animal gracefully disappears beneath the surface of the gray water. Needless to say, I was excited to see that the whales were back again and proudly pointed them out to a pair of tourists from Europe (take that, Eiffel Tower!).

I sent a message to Keener to report the sighting. And I was also wondering, given that this was now a recurring trend and not a one-time deal, if he could shed some light on why the whales were here and what it might mean about changing conditions in the Bay and ocean and how marine mammals are adapting to those.

Humpbacks have been plying the waters of the Pacific Ocean along the coast of Northern California for millennia, journeying between winter breeding grounds off the Pacific Coast of Mexico and Central America and spring and summer feeding grounds off the coast of California (and Oregon and Washington). However, following decades of industrial-scale hunting beginning in the late 1800s (including a whaling station on Point San Pablo in Richmond which functioned until 1971), the humpback population in the entire North Pacific Basin had declined precipitously from an estimated 15,000 in 1905 to about 1,200 individuals in 1966, just prior to the imposition of a ban on hunting humpbacks. The most recent estimates of humpback numbers in the North Pacific basin (which includes four “distinct population segments” that feed along the west coast from the Aleutians down to Mexico) is around 20,000, with an estimated 3,700 individuals in the so-called Mexico DPS (which breeds in Mexico and feeds along the California and Oregon coasts). According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), this particular population appears to be growing.

However, there is no indication of humpbacks coming in toSan Francisco Bay on a regular basis, even before the start of the whaling industry. The Richmond-based whalers had to go out into the Pacific to hunt their prey, and there is no reliable record of local tribal peoples hunting whales in the Bay. Many Bay Area residents are familiar with the story of Humphrey the “wayward whale,” who wandered into the Bay and swam up to the Delta in 1985. But as Keener points out, Humphrey was an individual whale who got off course and lost his way. These whales coming into the Bay now are not lost; they are coming in repeatedly, in pairs and groups, and on purpose. So why now? What has changed so that for the first time, as far as we know, humpback whales are regular visitors to this busy urbanized estuary?

Keener has photo documentation from 2012 of humpbacks in the outer portion of the Golden Gate strait, between Land’s End and Point Bonita. In 2015, he had reports of a few whales coming a little further into the outer part of the strait. But that all changed in April 2016, when whales started coming under the bridge and in to San Francisco Bay in force. In a single day in July 2016, researchers counted 24 different individual whales in the strait outside the Bridge, a record that still stands. A few days later, 15 whales were documented inside the Golden Gate, another record. Researchers continued to see humpbacks in the Bay through late August.

The whales returned in 2017, beginning again in mid-April and this time continuing through November. There were no record days as in 2016 (highest count was 10 in one day), but instead, fairly consistent numbers throughout the season. That pattern continued again in the spring and summer of 2018, starting again in April, continuing through the height of the season in May and June, and then tapering off in the fall. When I went out for the cruise in early September, the whales had departed the Bay and we traveled several miles off shore looking for them. But in early November Keener photographed a whale feeding under the bridge, making a second year in a row with a November sighting.

Video: Tagging a Bay Humpback Whale

The regular presence of these leviathans in San Francisco Bay, so close to shore and so visible, is giving scientists an unprecedented opportunity to learn more about them. Last summer, scientists from the Washington-based Cascadia Research Collective (one of the premier whale research organizations in the world) traveled down to the Bay Area for a day to radio tag humpbacks from a small boat – so much easier than doing this in the open ocean! The suction tags stay attached for only two to three hours, but during that time, the transmitted data showed that the whales were repeatedly diving down 100 feet or more. This is yet one more indication, says Keener, that the whales are here to feed. Keener calls this behavior “bulk feeding”, more akin to grazing than hunting. Unlike blue whales (another baleen whale that feeds off the California coast in the spring and summer), humpbacks are “diet switchers.” They can and do feed on krill, but they can also consume small bait fish, and that is what they are feeding on in San Francisco Bay, as well as down in Monterey Bay. In both places, humpbacks are staying and feeding closer to shore than previously known due to the schooling of large aggregations of anchovies closer to shore. When those fish are near the surface, the humpbacks will engage in lunge feeding, exploding head first out of the water. When the schools of fish are deeper down, the whales will dive down for them.

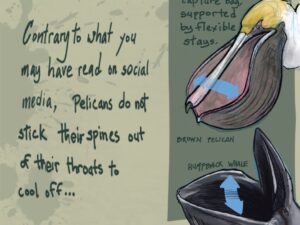

How do we know that it’s anchovies the whales are after? Keener shows me several photos of whales emerging mouth first from Bay, with anchovies spilling out of the sides of their mouths. He also reports a recent strange phenomenon of “fish falls,” where anchovies seem to be falling from the sky. No, they’re not flying fish; they are likely fish that had been scooped up near the shore by pelicans or terns or gulls, but then dropped when the birds are harassed by other birds seeking a share of the wealth. In any case, it is another sign of the abundance of the anchovy prey base close to shore. Keener believes that the whales’ presence in the Bay is due to a combination of growing whale population, which prompts whales to expand their search for feeding areas, and nearshore prey availability.

But that raises another question: Why are the anchovies gathering closer to shore? While it’s great for us land-dwellers to be treated to such close encounters with humpbacks, is this new “normal” a good thing or abad thing, ecologically? Is it a sign of changing (i.e. worsening) conditions for anchovies in the deeper ocean offshore? Is it a sign of a warming, acidifying ocean? Or is it part of some “natural” cycle? A 2017 study by the nonprofit Farallon Institute in Petaluma analyzes a documented decline in anchovy populations off the California coast from 2009-2015 and comments on the apparent nearshore abundance: “In low biomass periods, anchovy are known to contract their range inshore.” According to the institute’s president and senior scientist William Sydeman, “The abundance we’re seeing nearshore is an illusion. The anchovies are only occupying about 10 percent of their habitat. When they’re abundant, they range offshore. When they’re not abundant, they contract their range toward shore.” John Calambokidis of Cascadia Research warned in an article last year by Alastair Bland in Oceans Deeply, “With the decline in the prey base and the growth in the humpback population, there is the potential for stress on the population.”

Good or bad, Keener and his colleagues are taking advantage of the whales’ presence closer to shore to gather more information about them. Over the past three years, they have built up an impressive photographic archive of all the whales that have come in to the Bay. Poring over these photos —taken from boats, the shore, the Golden Gate Bridge — the researchers have been able to identify 61 individual whales, based on color patterning on their flukes, distinctive shape of their dorsal fins, or identifiable skin scarring. As more photos come in, and more individuals can be identified by their distinctive markings, the catalog grows.

Aiding Keener and his colleagues in this ambitious project is Joey Meuleman, a retired small businessman from southern Louisiana who recently moved to San Rafael. He’d been interested in photography since childhood, with a particular passion for trains. But after moving here, he was drawn to the Golden Gate Bridge – the views, the people, the changing weather. While there one day in 2016 he met a woman who pointed out a couple of whales in the water below and Joey was hooked. A few weeks later, she introduced Meuleman to Keener and a productive partnership was born.

According to Meuleman, he’d just been trying to get some nice whale photos. But Keener trained him how to focus his photography for research purposes and introduced him to Captain Joe of San Francisco Whale Tours. Meuleman says he’s been going out on the boat an average of three days a week. “It all just kind of fell into my lap, but it’s been great,” he says. “Now I’m doing stuff that’s not only fun, but also serves a good purpose.” Indeed; Keener estimates that a quarter of the hundreds of humpback photos in GGCR’s catalog were taken by Meuleman.

While some of the distinguishing marks on the whales likely come from attempted orca attacks, some also are from all-too-close encounters with water craft, both large and small. This is the main concern and potentially negative consequence of the whales’ presence in and around the Bay. In fact, it is the threat of boat strikes and fishing gear entanglement that prompted NOAA to maintain the threatened status for the Mexico DPS, despite the increasing numbers. The heavy traffic of ships and boats all along the west coast is a constant threat to this expanding population.

The Golden Gate in particular is a problem: It is a relatively narrow (one-mile wide) passageway through which sails a significant amount of commercial boat traffic (from small fishing boats to huge container ships) as well as plenty of recreational traffic. Several years ago, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) started gathering voluntary pledges from shipping companies to reduce the speed of their ships in the shipping lanes leading into the Golden Gate, in order to reduce collisions with the whales. But these lanes were developed before whales were discovered inside the Bay, and the guidelines are purely voluntary.

So GGCR is stepping up its effort to better understand the pattern of whale movements in relation to ship traffic, particularly when the whales are passing in and out through the Gate. Keener recently established a partnership with the Golden Gate Raptor Observatory, whose volunteers count raptors from the summit of Hawk Hill in the Marin Headlands from August through November. Hawk Hill is so-named because raptors migrating south along the coastal hills in the fall concentrate over the headlands before crossing the Golden Gate. But it is also happens to afford a perfect view down to the Golden Gate, allowing the volunteers to track whale activity below as well raptor activity above. GGCR hopes to be able to correlate the recorded sightings with tide charts to better understand when the whales are moving in and out of the Bay, as well as gain a better understanding of how the whales behave when large ships are approaching.

GGCR is also pushing for a public information campaign for people who regularly use the Bay—fishermen, kite boarders, kayakers, and sailors—to highlight the presence of these large new members of the diverse Bay community and discuss how to best accommodate them in this well-loved and well-used body of water surrounded by 8 million people.

Back out on the water on this overcast but calm day in early September, Captain Joe and the on-board naturalists are scanning the horizon for signs of the whales as we motor under the Golden Gate Bridge and head out past Point Bonita. The whales have moved away from the near shore areas where they had been spotted that morning, so we head further west. About eight miles out, we come upon a collection of more than a dozen fishing boats surrounded by flocks of gulls and murres, cormorants and pelicans (and even a few jaegers!). The charter boats are there for the salmon, which are there for the same reason as the birds: schooling anchovies. And sure enough, it’s not long before we sight the tell-tale spouts of humpbacks nearby, diving and lunging, spy-hopping and fin-slapping, putting on a captivating acrobatic display for the oooh-and-ahhing tourists and the photo-snapping naturalists. No matter how many times you see them, there’s that visceral – and pleasurable – jolt each time a whale explodes out of the water, extends its long fins, turns sideways and crashes back down on the surface of the water, producing a wall of spray and a resounding slap! before it disappears below the surface. They may be there for the food, certainly, but there is clearly a lot more going on for these large and complex creatures whose presence testifies to the biological riches of the Northern California coast. They have a lot more to tell us about our marine environment, and it’s good to know that we are, finally, listening.