At about the 8,000 foot mark, they start to appear. Pull over anywhere along State Route 108 going east through Sonora Pass and strain your eyes to the far side of Deadman’s Creek. There they will be: wagon ruts. An old road/pseudo trail begins to come into focus. Thousands and thousands of wooden wagons hauling themselves up, over and through a sea of granite. So many migrants passed through here that the ruts still remain to this day. Part of my annual visit to the Eastern Sierra is to pull over in my rent-a-car and silently stare at this artifact. I find it enthralling.

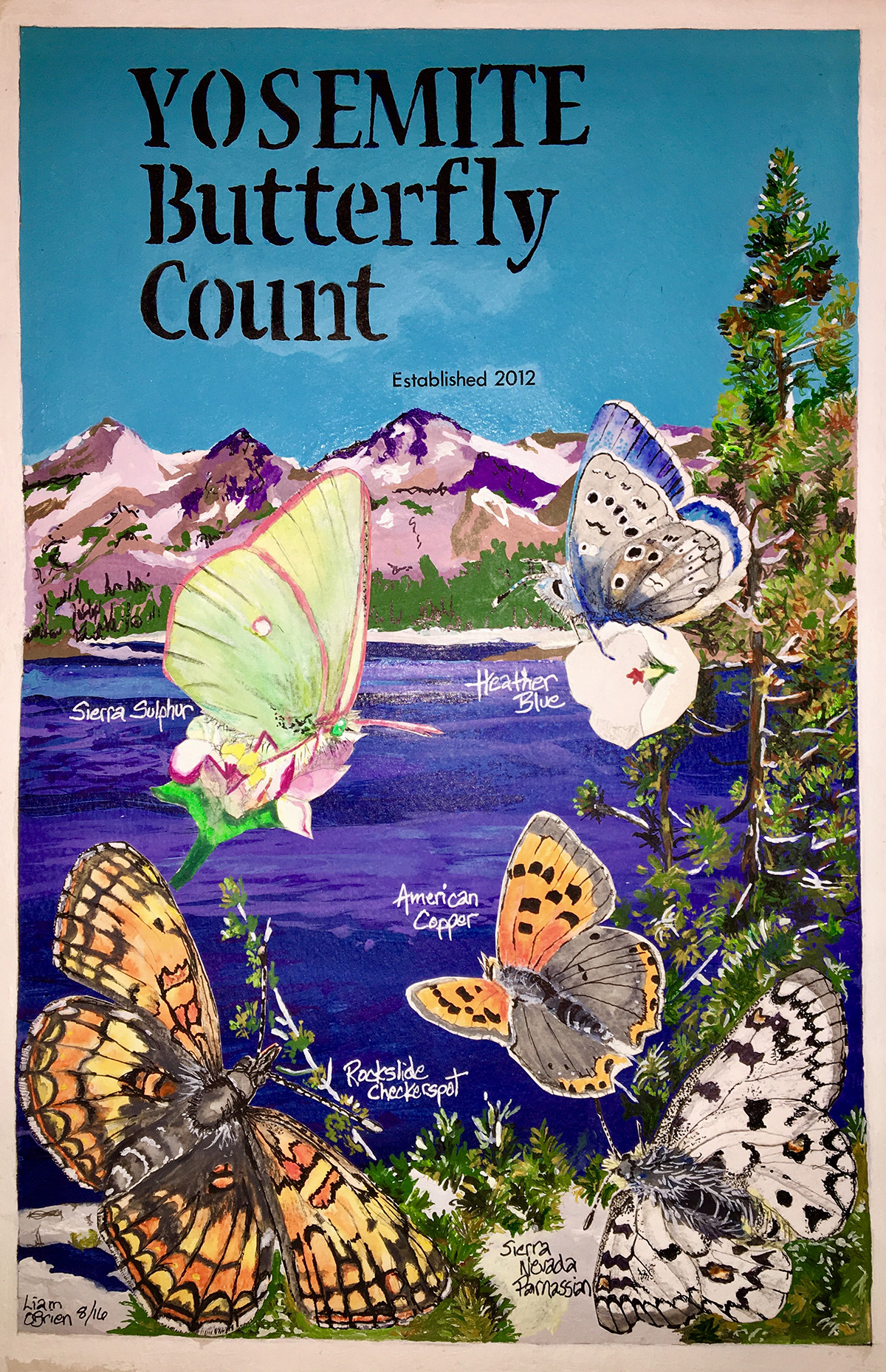

The first time I ever came to the Sonora Pass was July of 1997 for a now-defunct butterfly count. I’d hocked my entire Thomas Hardy paperback novels collection to give someone gas money to bum a ride there. Loosely based on Audubon’s long-running Christmas Bird Counts, butterfly counts are held annually throughout the country within an 8-week window of early June and late July. In the Bay Area, the first count of the season is at the Pinnacles National Park. I was on my way recently to the last count of the season — the Yosemite Butterfly Count. I’ve run the San Francisco Count for the last 12 years.

I’ve learned not to exit the car too fast after putting it in “park” up here. I began the day at sea level and am now stepping out at 9,650 feet elevation. Within minutes while making the brief hike to the summit, the altitude places its vice grip squarely on my temples and starts its squeeze. The Kodachrome plant wonderland of magenta mountain pride, indigo penstemon and raspberry buckwheat slurries together in a bowl of cold Fruit Loops up here. The wind is howling (bad for butterflies) while a Clark’s nuthatch laughs at this city boy in the distance.

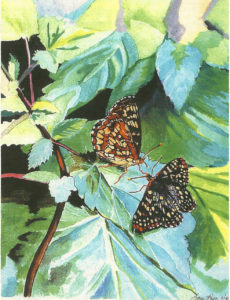

Two wondrous butterflies should be up here: the Chryxus Arctic (Oeneis chryxus) and Ridings’ Satyr (Neominois ridingsii). These two species used to be in the family Satyridaebut, as of this writing, the entire family has been absorbed by another, Nymphalidae. Perfectly camouflaged against the crumbling shale, they both actually hop around more like grasshoppers than butterflies. Short, explosive leaps then a landing with wings up, then…they fall to one side or the other, thermoregulating from the sun only on exposed side. That’s unusual for a butterfly — most normally bask both sides.

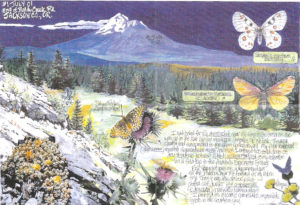

There are other high-altitude species up here, dominated by electric orange palette of Coppers — the American (Lycaena phlaeas), the Lustrous (L. cupreus) and the Ruddy (L. rubidus). Their variations-on-a-theme-of-orange would be stacked next to one another in any crayon box. There’s also Behr’s Sulphur (Colias behrii) — no other butterfly in California has a narrower range, and when all the other butterflies in the Pierid family are white or yellow, this one is green. There’s the Rockslide Checkerspot (Chlosyne whitneyii), a denizen of the bleak, skree field and a close relative of our Bay Area Northern Checkerspot (Chlosyne palla).

But none of those are the reason I’d come.

The plan was to meet up with Ken Davenport in Lee Vining for breakfast the next morning. One of the great collectors in California, Ken is also the author of Yosemite Butterflies (2007) and is the go-to guy if you want to know where — or-anything — about a particular species. I told him I’d like to see the Cassiope Blue (Agriages cassiope).

“Meet me back here tomorrow morning,” he said. “Bring lunch and lots of water. Brutal hike.”

Some of my grandfathers must have been born on a moorland, for there is heather in me, and tinctures of bog juices that send me to Cassiope, and, oozing through all of my veins, impel me unhauntingly through endless glacier meadows, seemingly the deeper and danker the better.

-From The Contemplative John Muir, by Steve Hatch

Butterfly “spots” are protected with vigor, like mushroom spots or fishing holes. I was surprised he didn’t suggest driving me there with a hood over my head in his trunk.

Also known as the “Heather Blue,” Cassiope was only described in 1998 and given full species status then, split away from the more common Sierra Nevada Blue (Agriades podarce). The Sierra Nevada Blue lives in wet meadows and the girl lays her eggs on shooting stars — a magnificent, beaked wildflower. The Cassiope Blue lives in a whole different ecosystem.

“Two hours up, two hours back,” Ken said, standing next to his truck, which looked like an episode of Hoarders. I stared at this 90-degree, talus scree field before me.

I thought, “Ken’s a big guy and has 20 years on me. I can do this.” A couple of fat, yellow-bellied marmots watched us from a safe distance, chewing plant matter in their chipmunk cheeks like baseball players chewing tobacco without the big spit. Progress was … nothing after a time. Each step up this Hillary Staircase felt like a slide backwards down a sand dune. A twisted ankle anywhere here was a nightmare to deal with. I started to boulder hop till my pounding chest reminded me what poor decisions I’m capable of.

In Paul Shepard’s book The Tender Carnivore, he breaks the hunt — something he refers to as “the venatic art” — into four parts: scanning (the knowledge of the animal’s habits), stalking, immobilization (catching) and retrieval (bringing it home). Since I don’t really collect anymore (nothing against it, and a subject I’ll tackle in a future column), my quarry for this day and mania for the last six years, is a photo of the butterfly to post on iNaturalist. (I go by robberfly there. The robberfly is a creature that eats butterflies, which I picked because, seriously, I wanted to … butch up the whole butterfly thing. Unfortunately, people now ask me to identify literal robber flies there, which I probably should have thought through.)

For me the immobilization has been replaced by one-good-shot-in-focus. The retrieval? Well, just getting my 57-year-old body back down uninjured: the retrieval of me. Shepard continues: “In all cases, however, men are engaged in more than a merely physical food-getting activity, for in hunting they are immersed in their most deeply held spiritual and aesthetic conceptions.”

“That’s the host,” Ken shouted, so loud it echoed through the rockslide bowl we were ascending. He pointed at a large area with an evergreen, prostrate bush spread out on the ground. The host plant is the plant, or family of plants, the girls lay their eggs on. I made my way to a spot to sit, the granite cold on my butt. First time I’d turned around in an hour, and all the icons were in the distance: Half Dome, Lembert’s Dome and the Olmstead Lookout. My altimeter read 10,500. Felt like sitting on the wing on a plane and all the monoliths before where made from clouds. I ate lunch and fought the impulse of barf it back up. Worth it because I was immediately rewarded with tiny blue butterflies patrolling madly over the bush — some actually nectaring on the beautiful bell-shaped flowers of the white heather (Cassiope mertensiana) — the butterfly’s host. Boys of many blue species patrol the host looking for girls — Mission Blues, Silvery Blues and even Pygmy Blues (the smallest butterfly in North America) all do this. I watched them till my pounding heart slowed down. In that moment, I was actually living Vladimir Nabokov’s famous quote: “To be in a rarified place with a butterfly and its host plant … all that I love rushes in like a momentary vacuum and … I am at one.”

“There’s one right next to you on a flower, ” Ken said. Slowly I moved my point-and-shot.

Someone told me when I got back to San Francisco that white heather was John Muir’s favorite plant. This is from Steve Hatch’s The Contemplative John Muir:

“Some of my grandfathers must have been born on a moorland, for there is heather in me, and tinctures of bog juices that send me to Cassiope, and, oozing through all of my veins, impel me unhauntingly through endless glacier meadows, seemingly the deeper and danker the better.”

Hatch adds: “The Scottish surname ‘Muir’ means ‘one who lives besides a moor.’ A moorland is a large, open tract of land covered in heather. Cassiope is a white heather that grows in the Sierra Nevada.”