Many people generally think of sea stars as slow, almost immobile animals, living in tidepools or in along the shoreline, feeding slowly on clams and mussels. So here’s something you might not know: sea stars can capture and devour small moving animals.

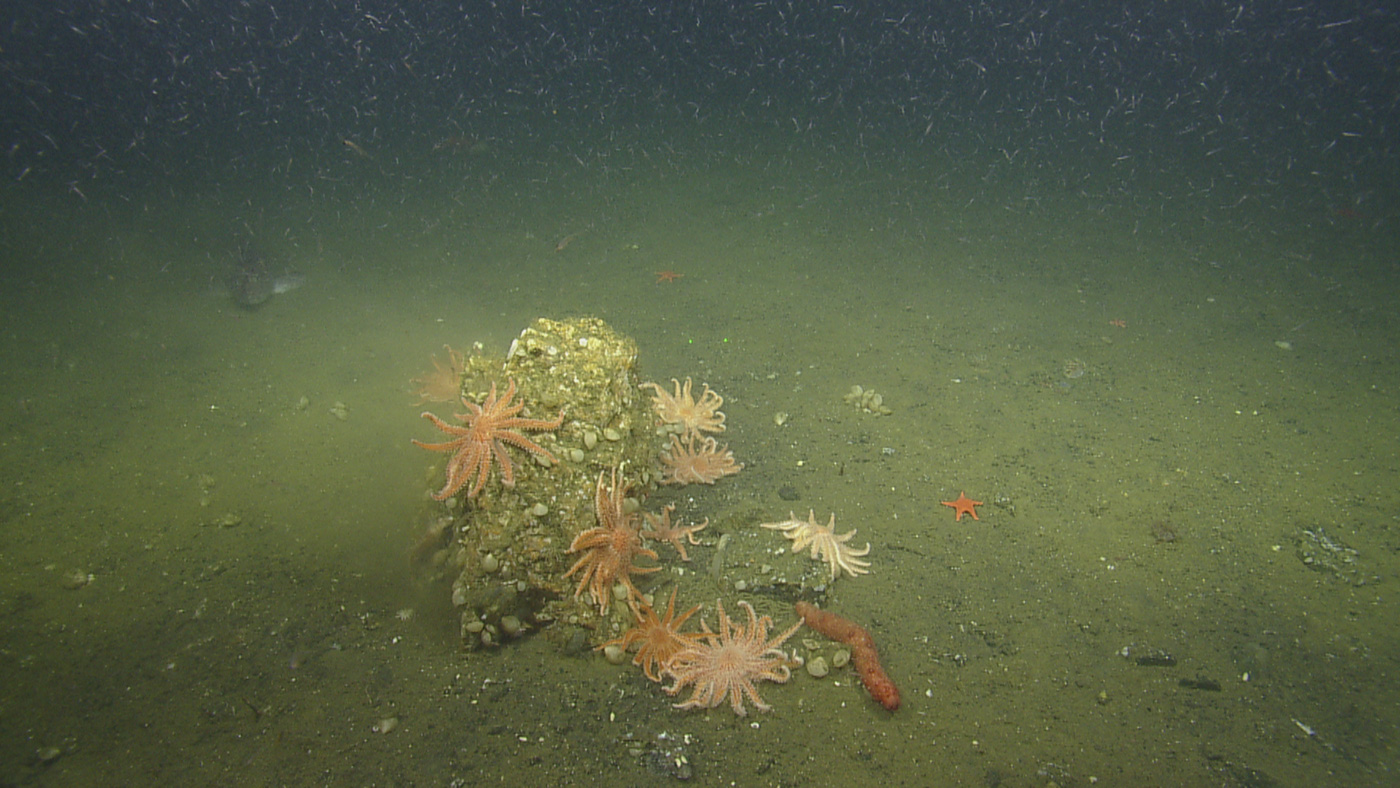

There are over 1,900 species of sea stars (also called starfish or asteroids) and they occur in oceans all over the world, ranging in depth from the intertidal to well over 6,000-meter depths. There’s a considerable diversity of form and biology within sea stars and although many sea stars are the more familiar shallow-water clam and mussel predators, there are many species that can do more! In early October, underwater robots from the exploration ship Nautilus captured a great moment of this fantastic behavior in the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Watch it Live: The Nautilus exploration continues this week in the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Follow the live stream at Nautilus Live.

One of the most frequently encountered deep-sea sea stars along the West Coast of North America, from British Columbia to Southern California is one that most people have never seen. It’s called Rathbunaster californicus, and it’s a pretty large animal. Most are about a foot across with some reaching a foot and a half. Each has between 8-22 arms, covered by spines bearing round wreaths of tissue which cover the surface and sides of the animal. Rathbunaster is a deep-sea species, occurring at depths between 100 and 800 meters. It was first described in 1906 by Dr. Walter K. Fisher, the director of Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, who named the genus in honor of Richard Rathbun, his colleague and scientist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (where I’m a research associate).

One of Rathbunaster’s key identifying characters is those aforementioned wreath-bearing-spines, which resemble pom-poms except that they are full of small, sharp wrench-shaped structures called pedicellariae. These wreaths can be moved from the base of the spine, when the animal is at ease, to the tips of the spines, and extended outward when the animal is feeling provoked, perhaps defensively, or when it senses potential food.

Feeding Behavior

When the animal goes into “feeding position,” it raises its arms and extends its tube feet, and these spines simultaneously extend their pom-poms full of pedicellariae (think small bear traps). All along the surface of the animal, but especially on the arms, these spines suddenly become pom-poms of death! Small animals, such as krill, which were observed in the nearby and surrounding water are immediately held fast to the pedicellariae present on the spines!

The tube feet then move the food from the spines on the surface to the underside of the arms, where the prey is eventually digested by the stomach and mouth.

The EV Nautilus videos captured the sea stars feeding primarily on small crustaceans, namely krill, but the first study to look at feeding in Rathbunaster noted that in addition to crustaceans, they also caught swimming worms, gelatinous animals known as siphonophores, and even small fish.

Beyond Rathbunaster, there are actually several sea stars which are capable of capturing active and more mobile prey.

Sea stars in the order Brisingida (also known as brisingids), for example, also feed by capturing food with their spines. Found in the deep sea worldwide, they feed in a manner similar to Rathbunaster, but have taken this manner of feeding to more of an extreme. Their skeletons are actually modified into frames, which permit the arms to extend into the water continuously in order to use their pedicellariae-covered spines to feed on crustaceans and other swimming food.

But perhaps the “grand winner” of sea stars that capture food is the Antarctic species, Labidiaster annulatus, which has upwards of 50 arms and approaches 2 feet in diameter. Similar to Rathbunaster, it holds its many arms into the water currents and uses its numerous and quite large pedicellariae with very wicked “teeth” to capture krill that approach too closely. Hapless prey are then moved to the mouth via the tube feet and devoured.

In addition to being able to make use of food in the surrounding water, Rathbunaster is also a voracious bottom predator similar to its sister species, Pycnopodia, feeding on everything from sea urchins to dead tissue and a variety of other animals.

Shallow and Deep-sea Sunflower Stars?

Many people will observe the images of Rathbunaster and notice a distinct similarity with a more familiar West Coast intertidal species, the sunflower star, Pycnopodia helianthoides. Although the two species are in different genera, molecular data has shown that the two species, Rathbunaster californicus and Pycnopodia helianthoides are sister taxa, that is, they are most closely related to one another than they are to any other known sea star in the same family (the Asteriidae).

Pycnopodia helianthoides is the shallow-water species, occurring in the ocean depths between the intertidal to somewhere between 50 and 100 meters, with the latter depth likely to be the very farthest extremity of the species. On the other hand, Rathbunaster occurs in much deeper water, between 80 and 800 meters.

Based on the molecular data, these two species diverged hundreds of thousands to millions of years ago, and have since occupied two different habitats separated by depth. It has long been a mystery what isolated these two species and what factors continue to influence the separation between them. Many questions about their relationship regularly come up:

-Where is the “break” between the two species? What depth?

-Are there environmental factors that keep them apart? Physiology? Ecology?

-Has one originated relatively recently compared to the other?

This has largely been an academic issue, until …this question:

-Does the deep-sea habitat protect shallow-water species that extend into deeper water from Sea Star Wasting Disease??

Suddenly these other questions attain a new level of relevance.

Between 2013 and 2015, a majority of shallow water sea stars from Alaska to Baja California died of something we’ve labeled Sea Star Wasting Disease, or SSWD. While the cause of SSWD remains an active area of research, cold-water temperature does seem to slow down if not halt the disease’s progress, depending on various factors such as severity of the infection and more.

As yet, there seems to be no clear evidence that SSWD has reached any of the sea star species inhabiting the deeper ocean depths, including Rathbunaster. Video observations of California’s deep-sea faunas have yet to produce evidence of the necrosis or discoloration we would expect to see with SSWD. Video and museum records have yet to show Pycnopodia inhabiting depths below approximately 100 meters, although there are some reports to the contrary, and so SSWD seems limited to shallow-water communities.

Rathbunaster californicus is a great example of how we are still discovering relevant and important new information about a species even though it occurs in a familiar locale — the Pacific Coast of North America — and has been known to science for over a century! It also paints an interesting picture of how a species that we might not see very often is nonetheless important to those of us at the surface.