From the top of a windswept hill, Craig Anderson gestures out over the green expanse of the Bohemia Ecological Preserve. From this vantage point, forested ridgelines march into the distance, framing steep ravines and sloping meadows.

“This is a really powerful place,” says Anderson, executive director of LandPaths, the nonprofit group to which the remote Sonoma County parcel was recently donated. “I think it’s going to affect a lot of people over the years.”

The property is best known for its waterfall, a short hike away from the Bohemian Highway, between the small towns of Occidental and Monte Rio. Despite its location on private land, the fern-draped cascade with a blue-green pool at its base has long been a favorite public destination. But the steep hills above the waterfall are home to many other ecological treasures, as Anderson demonstrates during a visit to the site along with biologist Brock Dolman.

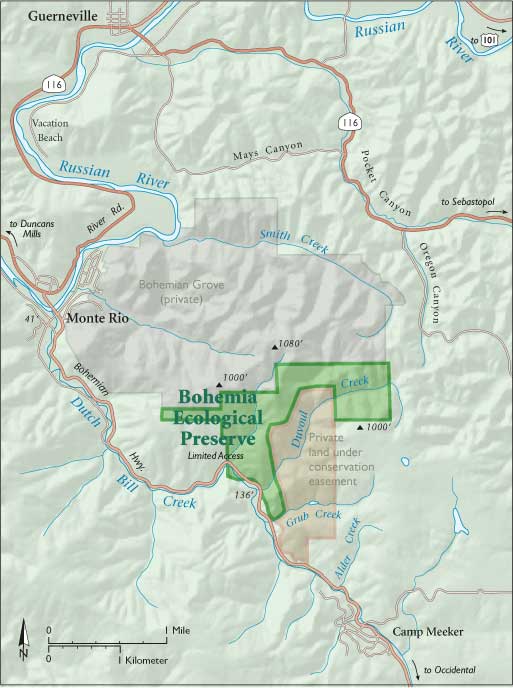

This 860-acre piece of land, known as Bohemia Ranch, is a conservation prize that neighbors and environmentalists have been working to protect for over a decade. This February, the protracted saga of hope and disappointment found a happy ending when a deal was struck between private landowners, LandPaths, and the Sonoma Land Trust. Just over 300 acres went to conservation-minded private owners, while the remaining 554 acres were donated to LandPaths, which owns two other properties and manages 4,500 acres of public and private land in Sonoma County. The organization, which runs extensive stewardship, volunteer, and outdoor education programs on its properties, will offer guided hikes and a docent program at Bohemia Preserve.

“This outcome for this property is perfect,” says Caryl Hart, director of Sonoma County Regional Parks. “It is an amazing piece of land; it’s really delicate and beautiful. When you have an area like this, you really want it to be preserved and protected.”

The wonders of nature

It is easy to see why the waterfall is so popular. It tumbles down a 30-foot-tall cliff face, between rocky canyon walls that rise up on either side. Mosses, ferns, and saxifrages decorate the stone in a lush palette of green, and gnarled buckeye trees cling to unlikely outcrops. Bay, live oak, and white alder stand on less precipitous ground, shading the boulder-strewn creek. As we hike up the narrow path, Anderson and Dolman point out favorite plants such as maidenhair fern and sweet-smelling vanilla grass.

The waterfall is on Duvoul Creek, one of three streams that drain from the preserve into salmon-bearing Dutch Bill Creek. Steelhead feed and breed in the lower reaches of the tributaries as well as in the main stem of the creek. Dutch Bill Creek is one of the most valuable streams for coho in the Russian River system, according to Dolman. And the streams of Bohemia Preserve are an important source of the cool, fresh water that the fish rely on to survive.

Just as important, ecologically, is the fact that the fish benefiting from this stream don’t actually live in most of it. “The waterfall acts like a dam, so the upper portions of this watershed have been fish-free for who knows how long,” says Dolman, gesturing upstream and explaining that some species thrive in the absence of predatory fish.

“There are frogs and salamanders all up through there. It’s a really significant stretch of creek,” he adds. “I’ve never seen more juvenile California giant salamanders.”

Later, as we bounce deeper into the new preserve in Anderson’s aged pickup, he gives me a primer on why this land is so compelling. A lot of it has to do with where it sits on the watershed. The preserve is surrounded by a lot of other undeveloped land, including the 3,000-acre Bohemian Grove (yes, that Bohemian Grove–known for its connection to economic and political power brokers) and several outdoors-oriented camps. Federally threatened northern spotted owls and California red tree voles live on the preserve, as do mountain lions, bobcats, gray foxes, and many more species.

“[Bohemia Preserve] connects all this surrounding wilderness,” says Anderson. “But it is also unique in the area.” He gestures at the neighboring hills: All are uniformly dressed in the deep green of second-growth mixed hardwood and conifer forest typical of the area. By contrast, Bohemia is a patchwork. As with the adjacent lands, there are dense forests that have rebounded after being logged. But the preserve also hosts a dark tuft of old-growth fir, hardwood riparian forest, thick stands of chaparral, oak woodlands, meadows of coastal prairie, and a grayish band of dwarf Sargent cypress, a California endemic that grows only on nutrient-poor serpentine soils.

“This property has an amazing mosaic of ecosystem types,” Anderson says. “It has suffered many insults over the last hundred years, but it’s resilient enough that there is still wildness here.”

The chaparral and cypress form an eerie and striking landscape, with stunted trees spreading their limbs over rough red-and green-hued boulders of serpentinite. Impenetrable thickets of manzanita grow under and around the trees. The rare Baker’s manzanita is common on this property, one of a small number of places it is found.

A series of coastal prairie meadows high on the hill represents one of the state’s most endangered vegetation communities, and those on the preserve are some of the most diverse. In the spring the meadows become a sea of wildflowers. The preserve is home to endangered Pennell’s birds-beak, and other rare flowers such as Sonoma jewelflower, Tiburon tarplant, and narrow-leaved daisy bloom here, as do more common species like goldfields, owl’s clover, Douglas iris, and blue-eyed grass.

“It’s a total botanical wonderland here because of the combination of the geology, abundant rainfall, and the steep and varied topography,” says Dolman. “You get these crazy endemic plants, species that occur almost nowhere else on the planet.”

A long, strange trip

Despite its vibrancy, Bohemia has endured a long history of hard use, including logging, ranching, farming, mining, quarrying, and off-road vehicle use. Before the land was sold in February, several marijuana patches were found in its remote corners. And the zoning for the parcel would have allowed future logging, as well as the subdivision and development of up to six different parcels.

The call for conservation began in the late 1990s, when the land was put up for sale. The waterfall was already a popular destination, and the environmental community had an inkling of the overall ecological value of the parcel. Soon a grassroots effort was launched to buy the land and save it from potential subdivision and logging. The push to turn the land into public open space– to be called Waterfall Park–culminated in a 1999 benefit concert featuring three members of the Grateful Dead (Caryl Hart’s husband Mickey, Phil Lesh, and Bob Weir) that raised $75,000 toward the purchase price. But it wasn’t enough; the galvanized public was sorely disappointed when the land was sold to a private buyer instead.

Though many were suspicious of Ted Swindells, the new owner, he spent the next decade doing valuable preservation work. With the Pacific Forest Trust, he established a conservation easement that eliminated the possibility of clear-cutting, and he also set about cleaning up some of the damage done in previous eras. He repaired roads, removed spent ammo and old car bodies, revegetated hillsides damaged by off-road vehicles, and built a hilltop campsite with tent cabins.

“When Ted [Swindells] bought this property, it was a massive tangle of off-road bad news,” says Anderson. “He likes fixing stuff up. He bought it for $3.2 million and, conservatively, he’s put about $3 million into the property since.”

As with many sagas of land ownership, the progress toward Bohemia Ranch becoming a preserve was riddled with complication and detail. In 2001, the Sonoma Land Trust took over the easement, recounts Wendy Eliot, the land trust’s conservation director. Meanwhile, Swin-dells began considering selling and pursued lot-line adjustments that would make it easier for a buyer to carve it up into smaller developable parcels, Eliot explains.

“The property has been on and off the market for years,” she adds, and many prospective owners met with her to discuss ways Bohemia Ranch might be managed as part of a public-private partnership. “But when the economy tanked, all the buyers ran away.”

In 2010, negotiations with the county’s parks department, the Sonoma Land Trust, and other stakeholders also hit a dead end. “Our vision never wavered. When the regional park idea fell apart we just went, ‘OK, now what?'” says Eliot. “We really had to get creative, so we could find a way to protect the land and also make it available to the public. I’m not going to sugarcoat this: It’s hard to get funding, even for great projects like this one.”

As the park plan faltered, LandPaths began to lead tours and hold volunteer restoration events even while Swindells still owned the land. A new, more restrictive conservation easement was placed on the part of the property slated to become a preserve. Swindells sold the upgraded easement to the land trust at a discounted price paid with a $1.4 million grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. He then donated the 544-acre parcel to the Sonoma Land Trust, which turned ownership of the property over to LandPaths– and the Bohemia Ecological Preserve was born.

“All the pieces had to come together like a really complex jigsaw–and out of that came a different kind of a project,” Eliot says.

People on the land

For now, if you want to see the interior of the Bohemia Ecological Preserve in person, you have to sign up for a guided hike or even better, says Anderson, sign on as a steward.

The new Bohemia Preserve will be run according to LandPaths’ “people-powered parks” model. Rather than being open to the public and run with public dollars, the preserve will be run largely by volunteers and supported by donations. You can go on guided hikes and volunteer on work days, but the preserve isn’t likely to be open to the general public any time soon.

“It’s a recipe that we’ve been working on for 15 years, and it’s very different from a [typical] park experience,” Anderson says. “The people-powered parks model that we developed is about transforming people from being park users to being park stewards.”

Volunteers at Bohemia will do everything needed to run a preserve, from leading hikes to removing invasive weeds to scouting for pot farms. “People are going to be out monitoring every acre of the preserve so we know what’s going on,” says Rebecca Abbruzzese, the organization’s parks and preserves director. “They are going to be our eyes and ears out there.”

Anderson and Abbruzzese both point out that not only does this approach reduce the cost of managing the property, but it also makes people who use it much more engaged.

“If we stop expecting people to be tourists and start expecting them to be stewards, change can happen really fast,” Anderson says. “We’re getting people to take ownership of a place–keep their eyes on it, help fundraise for it, and ideally go out there and get their hands dirty and sweat their shirts up.”

The philosophy is one that has been receiving a wide welcome, particularly in the current era of dwindling resources for state parks and other public lands. While it won’t be possible for individuals to visit the preserve freely on their own, “we’re in a brave new world right now,” Eliot points out. “Unfortunately the public funding that we’ve all relied on to keep our public parks and preserves open and in great shape is gone or limited. Into the breach have marched nonprofits and volunteers who can get the job done.”

Getting There

Bohemia Ecological Preserve is about halfway between Occidental and Monte Rio on the Bohemian Highway (which runs north from the Bodega Highway). It’s open only for guided outings and special events, so contact LandPaths for more detailed directions: outings@LandPaths.org, (707)524-9318.