t had been a long time since Mountain Lake was the kind of place where a western pond turtle could live happily.

For decades, the Presidio’s natural freshwater lake suffered environmental insults: runoff from Highway 1, sediment pollution, invasive species, voracious released goldfish. Mountain Lake had been “a cesspool since the ‘70s and ‘80s,” says Jonathan Young, a wildlife ecologist with the Presidio Trust. “It was a soupy, green, algae-scummy sort of lake.”

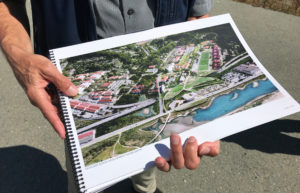

Not anymore. On Saturday, a few dozen people sat on a grassy slope overlooking the green, reflective surface of the almost completely restored lake, and waited for one of the final pieces: the return of the native turtles. They had to wait, however, for a few extra minutes. Some of the turtles intended for the lake, crammed into travel containers to make their way triumphantly from their previous home at the San Francisco Zoo, were stuck in traffic.

Jason Lisenby, who has overseen the restoration since 2012, stepped in with a short speech about the lengthy history of the habitat revitalization: the first removal, 14 years ago, of nonnative plants, the discovery that the bottom of the lake was so polluted with metals from Highway 1 runoff that the entire lake had to be dredged, the gradual post-dredging cleanup and eventual reintroduction of native underwater plants, the release earlier this year of Pacific chorus frogs and three-spine sticklebacks. While the project has been overseen by the Presidio Trust, thousands of volunteers have put in 20,000 hours of restoration work, Lisenby said, and they continue to meet every second Saturday of the month.

uring the hard years of restoration and cleanup, the Oakland and San Francisco Zoos, Presidio Trust, and Sonoma State were plotting to bring back the turtles. They started three years ago, harvesting eggs from a research site in Lake County and bringing the eggs to the San Francisco Zoo. The turtles had different mothers to promote genetic biodiversity, said Jesse Bushell, the director of conservation at the Zoo, who oversaw the turtle’s upbringing, and Bushell said she also tried to keep human interaction with the baby turtles to a minimum. They didn’t even give them names, she said — just numbers. “At the Zoo, they eat worms, crickets, mouse pieces, and fish, but they have not been hand fed,” she said. “They have to hunt for their food.”

So finally, after a decade of hard restoration work, three years of turtle-care, and 30 minutes of traffic on Presidio Parkway, on July 18 at 1 p.m. the turtles returned to Mountain Lake.

Lisenby had just finished answering questions when the van pulled up. A murmur passed through the crowd. Two uniformed Zoo employees opened the van doors and took out two large crates. The containers were carried through the crowd and placed behind the spectators, and as Lisenby handed the microphone over to Bushell, the turtles confronted their paparazzi.

The turtles were two to three years old and four to five inches long, about the size of western pond turtles twice their age because of their captive upbringing. Antennas fixed to the back of their shells will allow their locations to be tracked for two years, and Bushell said she hopes to someday get GPS monitoring for the turtles.

After a short speech, the turtles were loaded into a rowboat helmed by Presidio Trust Conservation Director Terri Thomas, who rowed to the release site. Members of the Zoo’s conservation staff and Sonoma State researcher Dana Terry, who has led the scientific study of the turtle release, waded around the edge of the lake.

hree weeks earlier, Terry had placed 14 turtles in a container in the lake on the west shore near the highway, to give them a chance to acclimate before their release. Those turtles would go first, and then the rowboat turtles would make the plunge straight from Zoo to lake as part of an experiment in restoration and reintroduction.

In waterproof overalls and waders, Terry edged slowly around the lake, gently pushing willow branches out of the way until he arrived at the release site. He and members of the Zoo’s conservation staff popped the lid off the container, and Zoo biologist Morgan Pyeha dipped a large, long-handled net into the container to fetch the first turtle. She handed it to Terry for final measurements.

The turtles will be recaptured in the coming months to determine their stress levels — measured by cortisol levels in the blood — which will help determine whether the period of acclimation helped. “We want to see how they use the lake,” Bushell said. “We want to see how they survive with snakes and raccoons.”

Young and Terry both said they think that a soft release method will be easier on the turtles. But they’ll find out, and then, based on the results, release another round of turtles at Mountain Lake on Sept. 12. As restoration continues, Young said he hopes to learn enough about amphibian health in the lake that he can also release a species of Pacific newt, as well as the California red-legged frog. There’s plenty to learn, and Mountain Lake isn’t the only experiment site. The Zoo is continuing work in Lake County, and has partnered with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to pursue future projects.

“Urban aquatic restoration is still a new 21st-century idea,” Young said. As the field continues to grow, other projects could turn to Terry’s results as a model for work in their own lakes.

But before they will next be observed by humans, the turtles have a new audience in the lake itself. As Terry conducted his measurements, a mother mallard and her five ducklings swam into the willows nearby to see what was going on. With the ducklings watching, Terry waded a few feet away from the shore and one by one, slid the turtles into the water.

“This one’s number 324,” he called out, and gently placed a wriggling turtle into the murky water, where it quickly swam out of his hand and out of sight. Number 324 was followed by turtle number 409 and then a turtle significantly smaller than the others. It stretched its neck towards the water, legs already windmilling as Terry brought it to the surface of the lake.

“This one’s our runt,” Terry said. “If he makes it, it’ll be a real success story.”