If you’ve ever poked around in an elderly uncle’s attic, you’ve got some idea of what it’s like to visit the nature lodge at Tilden Nature Area in the East Bay Hills above Berkeley. Nestled in a forest beside the Little Farm, it looks a little like a long, low storage shed. But there are signs of life. A child-size muddy handprint smudges each of its 13 small windows. Curling snapshots of kids with backpacks are pasted on posters inside. At one end of the room is a big stone fireplace. At the other is a corner filled with a tree stump, fishing net, birdhouse, bag of concrete, miniature pig trough, gallon jar full of pickled newts. A sign outside says, “Home of the Junior Rangers.”

Some 40 kids, ages 9 to 18, have gathered here on a cold Saturday morning in May. Last week they built boats out of recycled canvas and Scotch broom, an invasive shrub. The one-person roundish “coracles” look a little lumpy and, well, handmade. But they’ve been built for an important mission. There’s a shortage of safe resting places for western pond turtles in the region. Junior Rangers are going to paddle to the middle of nearby Jewel Lake to install floating turtle platforms. As the kids file out of the lodge to get their boats, a lanky, dark-haired teenager tells a friend, “I’m supremely confident!”

Unfortunately, many kids aren’t supremely confident in the outdoors these days. Some aren’t even interested. They suffer from what author Richard Louv calls “nature deficit disorder,” which he says can lead to problems like obesity and depression. In Louv’s book, Last Child in the Woods, a fourth grader sums up the problem: “I like to play indoors ’cause that’s where all the electrical outlets are.”

In the five years since its publication, this book has spawned a spirited movement with this motto: “Leave no child inside.” The East Bay Regional Park District has been getting kids outside for more than seven decades.

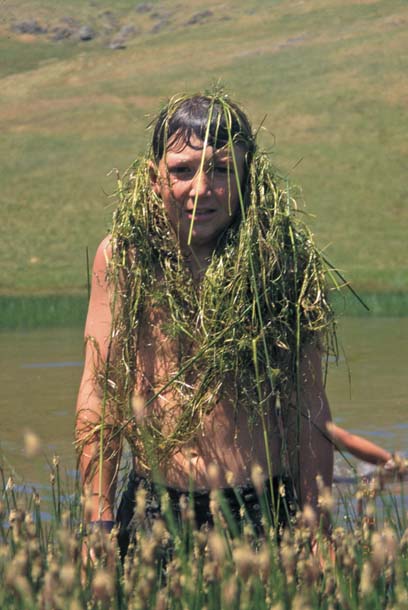

- In spring 2010, a group of Junior Rangers built small boats called coracles and paddled them out onto Jewel Lake to install floating platforms for basking western pond turtles. Photo by Nina Zhito, ninazhito.com.

These Junior Rangers at Tilden Nature Area, for instance, meet each week to hike, camp, fly kites, play in the mud, climb mountains, explore creeks, and generally help each other have adventures in nature. Once a month or so, they go on an overnight. Toward the end of the year, they take a three-day and a five-day trip. When I ask an immaculate 12-year-old in a pink T-shirt what her favorite J.R. activity is, she says, “mud fights.” Others say “catching bullfrogs,” “tying knots,” and “eating powdered eggs!” A girl who looks like Huck Finn’s sister says proudly, “If I had to do this at my school, no one would have the guts to go in the water or step in the mud. They’d say ‘Ewwww!'”

The hardships that Junior Rangers endure–involving odd food, wet weather, poison oak, bumpy bus rides, and long hikes–are badges of honor. “When you ask about their most memorable trip, they tend to mention the one where it rained all the time,” Tilden naturalist James Wilson says. “But they say it with a big smile.”

Junior Rangers is one star in a constellation of science and nature programs offered by the East Bay Regional Park District. All told, the district reaches 250,000 people each year with its interpretive events and programs. Its 35 naturalists form the largest corps of professional nature interpreters serving any local park district in the country. They’re based not only at Tilden, but also at Ardenwood Historic Farm and Coyote Hills Regional Park in Fremont, Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve in Antioch, Crown Memorial State Beach (Crab Cove) in Alameda, and Sunol Regional Wilderness southeast of Pleasanton.

On school days, the district works with kids and their teachers to provide experiences tailored to California curriculum standards. Nearly 59,000 students in Alameda and Contra Costa counties benefited from these programs in 2009. On weekends and weekday afternoons, the district also offers clubs that meet regularly, like Junior Rangers, as well as a multitude of one-time drop-in programs. Last spring, for example, kids could spend a few hours “Birding from a Cliff” or celebrating “Earth (Worm) Day” or trying a “Tule Basket Workshop.”

- Junior Rangers in Diablo Foothills Regional Park in 1995. James Wilson, on the far left, today leads such trips himself. David Zuckermann (center back) is now supervising naturalist at Tilden Nature Area, after leading Junior Ranger trips for years. Courtesy East Bay Regional Park District.

“The East Bay Regional Park District has one of the most widely known and well-respected interpretive programs in the country,” says Jim Covel, president of the National Association for Interpretation. “Their innovative programs are an inspiration.” It’s also one of the better-funded local park programs, because a set percentage of local property taxes is earmarked for the district.

- James Wilson, now a park district naturalist, as a Junior Ranger in 1996. Courtesy East Bay Regional Park District.

Teaching kids about science and nature has been a priority for the park district since it was established in 1934. Beginning in the 1960s, though, “we grew from two or three naturalists to a mini-army,” says Ron Russo, who signed on as a naturalist in 1966, rose to become head of the interpretation and recreation unit, and retired in 2003. “Nobody was telling us what to do. We were free to invent and fall flat on our faces, and get up and do it again until we got it right. As a result, we developed effective teaching techniques that are still used today.”

District naturalists don’t lecture kids as they walk from stop to stop, a pedagogical method one of Russo’s colleagues calls “brag and drag.” Instead they help kids discover things for themselves. When one of them spots an interesting leaf or feather or track in the sand, “you ask questions and get them physically and mentally involved,” Russo says, “through looking, smelling, touching, and talking among themselves.” Soon the kids start asking their own questions and soaking up facts they’ll remember.

Tilden naturalist James Wilson took his first guided hike in the district when he was only five years old. “The naturalist had this aura about him that made me want to listen,” Wilson says. “I remember being right up front, biting his heels.” At dusk, the hike leader rummaged around in his pack and pulled out some kindling and a flat metal pan. Setting the pan in the middle of a dry creek bed, he built a fire. Then he passed out parboiled potatoes to roast on sticks. “I don’t remember what the purpose of the hike was,” Wilson says. “But it was one of the most memorable I’ve ever been on.”

“That was the portable campfire program,” chuckles Tim Gordon, the retired Tilden naturalist who led that unforgettable spud roast. Gordon is a font of nature facts, but his highest goal on that hike–and on countless others he led during his 34 years with the district–was to make sure the kids had a good time. “I want them to grow up loving this place,” he says.

Gordon has a list of suggestions for younger educators. It includes the basic “Don’t harm wildlife” and the practical “Build things out of materials at hand.” But it’s mostly about fun: “Dance across meadows; Make up stories; Don’t be afraid to sing; Lead night hikes; Hoot up owls; Be silly; Call to your echo; Balance on logs; and Fall in the creek.”

“Don’t worry about scientific names,” Gordon advises, “except when you go by that outcropping of blue glaucophane schist. When you’ve got a name that sounds like a sneeze, you want to use it!”

Because Junior Rangers involves overnights and challenging hikes, participants have to be at least nine years old. Many kids stick with the program for years, first as Junior Rangers, then as Junior Ranger aides, until they finish high school. But the district has programs for much younger children, too, starting at age three: Tots N’ Sibs at Tilden, Toddler Time at Ardenwood, Sea Squirts at Crab Cove, and Outdoor Discoveries at Sunol.

- Katie Colbert, a naturalist at Sunol Regional Wilderness, holds a western fence lizard for a child at one of the park’s weekday education programs. Photo by Nina Zhito, ninazhito.com.

Katie Colbert, a naturalist who leads programs at Sunol and has worked for the district for 28 years, tries most of all to make young children feel at home outdoors. Her curriculum is not about that abstraction called “the environment.” It’s about the specifics of place: plants, animals, indigenous peoples. Armed with that knowledge, children aren’t bored by nature. They know what to look for.

The day I visit, Colbert has prepared an Outdoor Discoveries program called “Ants, Wasps, and Bees, Oh My!” A four-year-old we’ll call Tyler dresses up as an ant, in a hat with googly eyes, a plump black vest, and a long black cushion tied on at his waist. He transmogrifies into a bee by adding yellow Velcro stripes to the cushion and straightening out his crooked antennae. Soon afterward, another four-year-old, whom we’ll call Sara, dons a bumblebee disguise, and she and Tyler start buzzing around the room. “I’m going to sting you!” Sara shouts.

Colbert cuts off the impending chaos. “Now we’re going to go look for some ant food,” she says. “I’m not going to do nothing!” says Sara. Colbert ignores the outburst. “When ants live together in one big family,” Colbert continues, “they tell each other where the food is, and they talk to each other by smell. We’re going to follow a smell trail that was left by a huge ant to tell us where a treat is.” The kids put on antennae they’ve made out of paper and pipe cleaners and walk outside in ant-like single file. In the grass ahead are two lines of Dixie cups. One line curves off to the left, the other to the right. Each cup has a cotton ball inside, but only those heading to the left are doused with almond extract. The kids are supposed to sniff their way to a box of crackers hidden beneath an oak.

Before the sniffing begins, though, someone spots a western fence lizard skittering across dry leaves. This wasn’t part of the plan, but Colbert catches the creature, being careful not to grab its detachable tail. The kids form a tight circle around her and watch in silence as she calms the reptile down by rubbing its bright blue belly. One by one, each child is allowed to touch.

Near the end of the two-hour session, the kids seem a little calmer, more able to focus. Especially Sara. When she showed up in the nature center this morning, she was staring at her pink iPod, refusing to speak to anyone or go outdoors–a classic example of how virtual entertainment can keep kids from real experience. “She’s concentrating on her game,” her babysitter said apologetically. Within 10 minutes, though, Sara is happily telling Colbert about her favorite insects, her iPod upstaged by the well-trained naturalist.

- Naturalist Tara Reinertson captures samples from the Bay at Crab Cove in Alameda using a seine net. She gets help from a fifth grader from Arroyo Seco Middle School in Livermore. Photo by Joan Hamilton, joanhamiltoninfo.com.

While digital devices can be a distraction in the field, the district is also using them to help kids learn. Rick Parmer, the district’s current chief of interpretive and recreation services, explains, “We recognize that the world is changing. Today you can become a birder with your iPhone. We see a tremendous opportunity to use technology to reach the younger generation.”

- An Arroyo Seco Middle School student looks for evidence of subterranean life in Bay mud. Photo by Joan Hamilton, joanhamiltoninfo.com.

Last spring I witnessed this pedagogical jujitsu in action at Crab Cove, where some fifth graders from Arroyo Seco School in Livermore are studying San Francisco Bay. “We get to pretend we’re scientists,” naturalist Tara Reinertson tells one cluster of kids. Soon they’re pulling on hip waders and walking out into the Bay. The soupy gray mud is slippery and full of signs of life: ghost shrimp burrows that look like miniature volcanoes, mounds of lugworm castings, and depressions scooped out by bat rays. “This is why I love the ocean,” a boy with a buzz cut confides. “You get to see things you’ve never seen before.”

With the help of Reinertson (and a scientific collecting permit from the state), two youngsters stretch out a seine net in the bay. First they hold the net vertical. A few minutes later, they turn it upward to reveal a catch of lugworms, sculpin, a goby, snail eggs, and shrimp. One of the seine-netters gets so excited that he begs someone else to hold the net so he can cradle a two-inch-long sculpin in his hand.

Later, the fifth graders plunge a post-hole digger into the mud at different depths and sift through the diggings with a screen. Peering into a microscope, they’re full of exclamations: “Whoa, it looks like a big caterpillar!” “It’s moving!” “That is so cool!” Finally, the kids are asked to draw and describe one of four creatures in an aquarium: a small snail called an Atlantic oyster drill, a shrimp-like sideswimmer, a bay mussel, and a shiner surfperch. “Pretend you are the first person ever to find these animals,” says Crab Cove naturalist Sharol Nelson-Embry. “Describe their sensory organs, their interactivity.”

This is all exemplary hands-on science–what the district is well known for among environmental educators. But this Arroyo Seco class is breaking new ground by combining science with what Parmer calls “digital storytelling.” A crew from KQED’s Quest science journalism program has taught district staff to document the sights and sounds of the program. They’ve worked together to create a movie of the student drawings, writings, photographs, and voices to be posted on the Encyclopedia of Life website (a scientist/citizen collaboration inspired by biologist E.O. Wilson at Harvard). As the project evolves, students who visit Crab Cove could monitor species in mudflat quadrants, chart their findings, and make them available to scientists worldwide through the Encyclopedia of Life. Used in this way, Parmer says, technology can enrich students’ experiences in nature. “This approach gets young people to care about science by doing projects in the field and sharing their work online,” Parmer says.

- Park district naturalist James Frank visits schools with a mobile aquarium so that kids who might not make it out to the district nature centers themselves can learn about local aquatic wildlife. Courtesy East Bay Regional Park District.

As the district works to enrich its programs, it’s also broadening their reach. Since the mid-1960s district naturalists have been expanding opportunities for underserved communities, including low-income families, seniors, and people with disabilities. In 2009, the district added a new mobile visitor center and fish exhibits, which bring naturalists, live animals, and teaching materials to kids in Alameda and Contra Costa counties who can’t make it to one of the district’s six nature centers. Schools with high percentages of students participating in the free and reduced-cost lunch program are a top priority. The district is reaching out to low-income families in other ways, too, by partnering with community groups that serve them and providing low-cost transportation to the parks.

Last August, at a potluck dinner celebrating the 63rd year of Junior Rangers, I get a glimpse of how lives have been changed by these outdoor programs. Among those here is Dave Collins, who was a Junior Ranger in the 1960s. After studying geology at UC Berkeley, Collins chose to work for the East Bay Regional Park District instead of an oil company. Today he’s an assistant general manager at the park district.

Also attending are nature photographer Joe Holmes and environmental consultant Dan Holmes (no relation), who were Junior Rangers in the 1950s and ’60s. From a generation later, there’s Eveline (Sequin) Larucea, now a field biologist at the University of Nevada, and Eric Nurse, who manages district lifeguards. Aya and Sayo Costantino, sisters who were Junior Rangers in the 1990s, sent their regrets because they are busy hiking the 2,650-mile-long Pacific Crest Trail.

Decades ago, renowned local photographer Galen Rowell was a Junior Ranger. Other graduates became mapmakers, schoolteachers, emergency medical technicians, and outdoor educators.

For a moment, I try to imagine a Junior Rangers reunion 20 years hence. Will district programs nurture new generations of scientists, photographers, and just plain lovers of nature? Retired naturalist Russo has no doubt. “I don’t think there’s anything that touches kids more personally than these kinds of programs,” he says. Having seen the delight in so many young faces at Tilden, Sunol, and Crab Cove, I’m hopeful too. “Today’s kids may have more competing demands for their time,” naturalist Colbert says, “but once you get them into the park they’re as curious and enthusiastic as ever.”

Find program listings at ebparks.org/activities. Note that due to construction on the Calaveras Dam, weekday programming at Sunol Regional Wilderness will stop on May 1, 2011, for an indefinite period.

.jpg)