Leafcutters, diggers, carpenters, and masons… At first glance that may look like a directory for building contractors. Add the miners, cuckoos, and sweats and what you have isn’t a list of tool-bag clad builders, but some of the 1,600 known species of native bees in California.

Recent research has found that these bees, which come in all shapes, sizes, and colors, are more diverse and more important for pollination than was once thought. Check out our feature In the Key of Bee to learn more.

The most important lesson gleaned from urban bee studies is that anyone–even with a small planted patch or balcony garden–can help by planting bee-friendly flowers and by building a simple home for bees.

Most native bees are solitary, so creating an acceptable artificial habitat is a lot simpler than trying to replicate a big honeybee hive.

One way to create a space for native bees is to build a bee block, which is: a large chunk of wood with different sized holes drilled in it to mimic ideal bee homes. The addition of a backyard bee block can help offset some of the habitat loss that come with the pavement, concrete, and development of an urban environment, but it will also help the productivity of your garden. “Native bees provide a service,” says Vance Russell, “if the habitat is available.”

Russell, who is the director of the Landowner Stewardship Program for Audubon California, uses bee blocks as an education and conservation tool. There are three simple practices, he says, that can really help the native pollinators: having diverse plants with varied bloom times, building bee blocks, and leaving ground bare in yards and gardens to accommodate ground-nesting species. Since native bees either nest on the ground or nest in cavities, having both options available will attract more pollinators.

“Bee blocks are really easy to make, you can just use scrap wood,” says Russell, “they almost always get occupied immediately.”

Brian Murphy, who works with Mount Diablo Audubon, says that about 35% of local native bees will use wood to nest.

He explains that since native bees are solitary they are generally not territorial or competitive and so different species will share the same bee block if there are different sized holes.

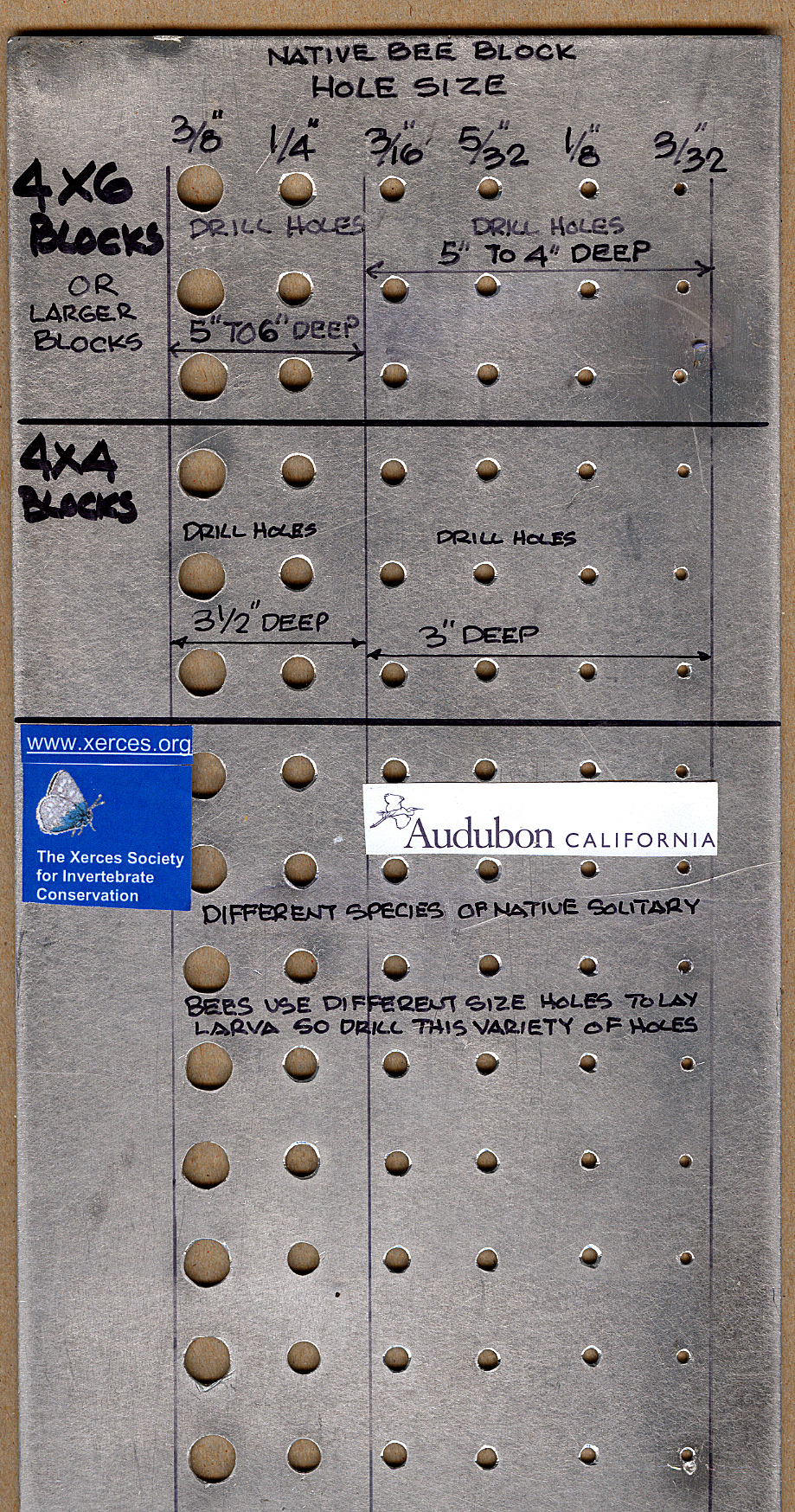

Scraps of 4×6 are the best choice for a bee block. It’s recommended to drill holes that are 3/8″,1/4″ 3/16″, 5/32″, 1/8″, and 3/32″ in diameter. The larger holes (the 3/8″ and the 1/4″) should be drilled about five to six inches deep. The rest can be shallower. Whatever size block you use, don’t drill the hole all the way through. Blocks made from templates show nice orderly rows and columns of holes, but it’s not necessary. “The bees don’t care if the holes aren’t straight.” Murphy says.

- Click on this template to see a full-size version of this image, which you can use as a template to make your own bee block. Photo courtesy Brian Murphy.

Having a bee block nearby is also a great way to learn about variability among different bees’ reproduction. Some bees deposit eggs early in the season and the adults will emerge before the end of the summer, while other species’ larvae will over winter in the blocks and emerge the next year.

Murphy says blocks should be hung facing east to catch morning sun, and tilted slightly forward so that water will not enter the holes and drown the larva.

Creating bee habitat is just part of what you can do. To maximize diversity, plant a range of different native flowers as well. Find out more from the Urban Bee Gardens page maintained by the lab of UC Berkeley bee expert Gordon Frankie, who has done research that links the seasonal timing of native plants with the presence of different species of native plants.

You can find bee blocks in use locally at Lindsay Wildlife Museum and in the Bancroft Garden at Heather Farms, both in Walnut Creek.

.jpg)