The news about a Bay Area millipede species with 750 legs has gone viral, for the obvious reason. 750 legs is not just leggy, it’s the leggiest animal known on Earth.

But it’s not the discovery of Illacme plenipes that’s made headlines. That happened back in 1926. Nor its rediscovery. That happened in 2005. Rather, the eye-less, pale millipede with big antennae is gathering attention because of new details about its modest existence that might explain why it evolved all those legs.

In a paper published this week in the journal ZooKeys, entomologist Paul Marek and his coauthors theorize that Illacme plenipes is uniquely adapted to its small niche living under sandstone boulders in the Gabilan Range, between Salinas and San Juan Bautista.

“The great number of legs may benefit a deep subterranean lifestyle clinging to sandstone,” Marek and the coauthors write.

Apparently it moves by boring and wedging its way into the ground, and the legs help give it more force to do so. Alternatively, maybe it’s the trunk that explains its length, and the legs that fill it. A longer trunk allows Illacme plenipes to store more eggs, and consequently the females are the only ones known to reach the 750-leg record. Or the long body could allow Illacme to extract more moisture from its food (all millipedes eat decayed plant matter), since it lives in such a seasonally dry environment.

Illacme adds legs after birth in a process known as anamorphosis, and the researchers have found that this goes on after sexual maturity.

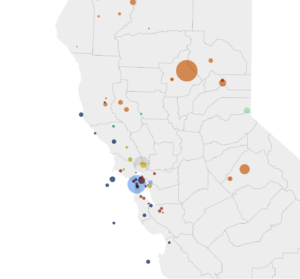

Despite the name, millipedes fall way short of the 1,000 mark. Most have been 36 to 400 legs, although the class contains an astounding 10,000 species. Illacme plenipes belongs to the Siphonophorida order, which mostly live in the tropics. The genetic similarity between Illacme and its closest living relative in South Africa lead the researchers to believe that it’s changed very little over hundreds of millions of years, which may say something significant about its home in moist, oak-wooded valleys in the Gabilan Range.

“This idea raises fascinating questions about climate and habitat constancy where Siphonorhinidae occur (its six regions also happen to be global biodiversity hotspots), and also important concerns about the conservation of the species and co-inhabitants that may have persisted in these mild climates that are now currently threatened by global climate change,” the authors write.

Sadly, it turns out that climate change combined with habitat destruction could spell the end of Illacme, which has been around in one form or another since at least the breakup of Pangea 200 million years ago. Rampant development and intense land use in the area are taking a toll. Climate change is also reducing the amount of ocean fog in Illacme‘s home range, and fog could be critical to stabilizing the environment in which it thrives.

“The documented 33 percent reduction in coastal California fog due to higher atmospheric and ocean temperature since the early 1900s … may severely impact the species and hasten its extinction,” the authors write. “The few locations where Illacme plenipes exist are unique storehouses of this evolutionary relict, and potentially other ancient lineages that await discovery.

Setting aside world record in number of legs, Illacme is not the most charismatic of species to drive home the need for conservation. But it’s got its own charm.

“There’s some repulsion (to millipedes), but they’re really quite gentle,” Marek said in an BBC interview. “And none of them are predators, none of them feed on flesh or live animals. And they’re kind of like little cows of the arthropod world. They’re gentle, slow and pretty friendly in general.”

Alison Hawkes is the online editor for Bay Nature.