What is way smaller than the dot on this i, helps scientists understand the climate of ancient times, and makes some people sneeze like crazy in the spring? The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind: pollen.

Pollen is a Latin word meaning “fine flour.” Each grain of pollen is tiny–hundreds of them fit on the head of a pin, and we can only see an individual grain clearly with magnification.

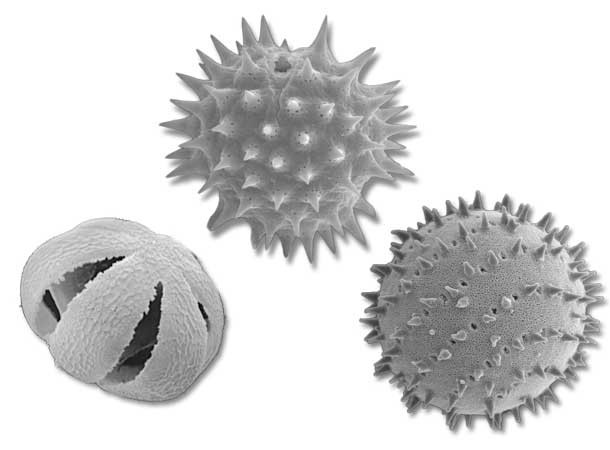

Pollen grains from different kinds of plants have different shapes with beautiful patterns and spiky projections on their surfaces. Often pollen is yellow, but it also comes in blue, orange, red, pink, purple, green, white, and even black.

Tiny as pollen may be, it is one of the most important materials on earth. Pollen is the living package in which plants’ genes travel from flower to flower. While animals can roam to find mates and reproduce, plants are rooted in place and need a different way to mingle. Pollen carries a plant’s male reproductive cells from one flower to another (that’s called pollination), where they unite with female cells deep inside the flower to form seeds.

- Look closely and you can see clumps of the lily’s red pollen. Photo by Ambarish Goswami, jagatjorajaal.com.

Because pollen can’t move on its own, the process of pollination requires assistance from pollinators that can move, like insects. Many flowers have sticky pollen that clings to the insects (or hummingbirds or bats) that are attracted by the flowers’ nectar and showy colors.

The pollen of other kinds of flowers is carried by the wind. These flowers are usually quite small and don’t have brightly colored petals–in fact, many don’t have petals at all. Wind-carried pollen is dryer, lighter, and often much smaller than insect-carried pollen. It is produced in huge quantities and can travel great distances, which increases its chances of landing on a flower of its own kind. Wind-carried pollen is what makes us sneeze in the spring.

That sneezing is one of the body’s defenses against harmful foreign invaders. When some people breathe in pollen, their immune systems treat it as an invader and produce chemicals to eliminate it, causing uncomfortable allergy symptoms.

Here in the Bay Area, plants with pollen that causes allergies have flowers we often don’t notice. In late winter, trees are the main culprits, especially oaks and birches. In spring, it is grasses (yes, grasses have flowers!) that cause most allergic reactions.

- These otherworldly black-and-white balls are super-magnified images of single pollen grains from the flowers of self-heal, common sunflower, and checkerbloom. Pollen grains: Left, courtesy Gretchen D. Jones, USDA-ARS, APMRU; center and right, courtesy Louisa Howard, Charles Daghlian, Dartmouth College.

But pollen does far more good than harm. After all, where would we be without flowers and plants?

And scientists called palynologists use pollen to learn about the earth’s past. Pollen grains’ protective outer coat can survive intact for thousands or even millions of years, so palynologists looking at layers of ancient sedimentary rock with powerful microscopes can identify different types of pollen fossils and determine which plants produced them. Knowing how old the rocks are and what climate those ancient pollen-producing plants needed to live helps us understand the climate of their times. And as we learn how climate changed in the past, we can understand more about climate change today.

So let your spring sneezes remind you that one of nature’s most important materials is blowin’ in the wind!

Get Out!

- This flower called pussy ears has purple pollen. Poto by John W. Wall, jwallphoto.blogspot.com.

This spring, look inside flowers for colorful pollen on your own or with a naturalist on a guided walk. There’s no need to pick the flowers, just get down to their level with a cheap magnifying lens to see orange pollen in poppies and lilies, blue in gilias and pussy ears, purple in phacelias, white in clarkias, yellow in roses, and much more. (If you have allergies, skip the grass flowers.)

Or take a Wildflower Scavenger Hunt on April 10 at Almaden Quicksilver County Park in Santa Clara County [10 a.m.-2 p.m., free, (408)355-2240]. See plants under the microscope at UC Berkeley’s University and Jepson Herbaria on Cal Day, April 17 [9 a.m.-4 p.m., free, calday.berkeley.edu]. In the Berkeley hills, join naturalist Linda Yemoto and the Tilden Explorers on April 22 for a children’s wildflower adventure [ages 5 to 7, adult companions welcome, 3:15-4:45 p.m., $6, register at (888)327-2757 (option 2, then 3) or ebparks.org/activities]. At Cascade Canyon in Point Reyes, learn the connections between wildflowers, butterflies, and birds in the Butterflies and Wildflowers for Families exploration with naturalist Wendy Dreskin on May 1 [10 a.m.-3 p.m., $20, register at (415)663-1200, ext. 373].

.jpg)