T

here are at least 250 plants known to have grown on Mount Tamalpais yet that have not been seen in recent years. Trudging along the mountain’s northern flank in 90-degree heat, a motley crew of bona fide botanists, plant enthusiasts, and me, the neophyte, hope to check a few more species off that list. We’re part of a Marin Municipal Water District “plant safari,” a citizen science effort to document every kind of plant growing on the mountain. Wiping away rivulets of sweat, we file in behind Andrea Williams, a vegetation ecologist with the MMWD and leader of our party. I’m considering all the plants I’ve overlooked in the past 15 years while running, mountain biking, and hiking on Mount Tam. Poison oak—more precisely, avoiding poison oak—is all I’ve ever really thought about.

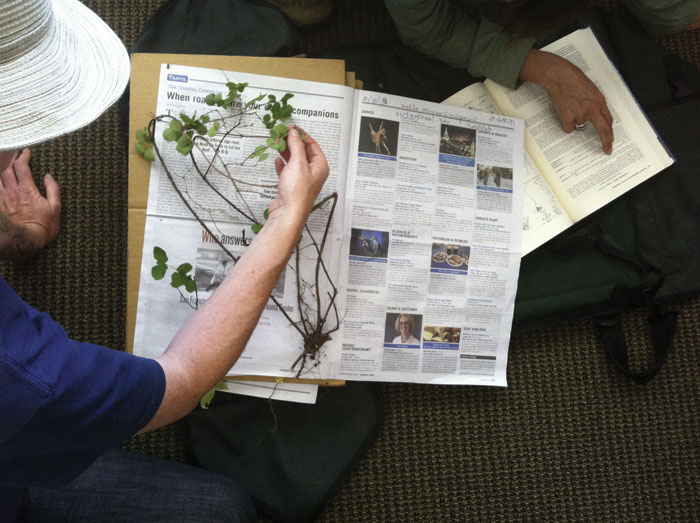

Suddenly, Williams is down on bended knee, inspecting a wiry, drab green plant. In no time Robert Brostrom, a fellow citizen scientist on our expedition, is sprawled on the ground, propped up on his elbows with his nose buried in the 1,500-page Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California. Along with this tome, we’ve lugged along a pickax and a field bag filled with cardboard sheets ready to hold the plant pressings we collect.

Williams thinks the plant is Cordylanthus pilosus, also known as hairy bird’s beak. I may be the novice in the group, but even to me the name makes sense — the fuzzy, mauve sepals look like two halves of a long beak gulping down a white flowery morsel. Although Williams is stoic and focused in the field, I later learn it’s one of the best discoveries of the day. “The Cordylanthus we found is in the only location I know of in Marin outside of China Camp,” she’ll tell me. Cordylanthus pilosus grows in the mountains and foothills of Northern California, and the subspecies we found — subspecies pilosus— grows only in the coast range region. “There are old vague records — ones that reference Fairfax or Mount Tam,” Williams says. “That’s the point of the safaris!”

Indeed, the plant safaris, organized by MMWD and the California Academy of Sciences, aim to produce the first-ever complete catalog of the more than 950 plant species botanists believe grow on the 18,000 acres of the mountain under MMWD’s purview. With that baseline information, the district will be able to monitor changes in the vegetation over decades to come and better manage the property. The project, now in its fourth year, is Williams’ brainchild. And it has nearly reached fruition.

The idea took root in 2012, the water district’s centennial. “Some of us in the natural resource department wanted to celebrate the natural history of the mountain,” Williams recounts. “I thought it would be good to have a snapshot in time, a baseline [of plant life].”

Williams reached out to the academy, with its long, rich history of botanizing Mount Tam, to inquire about collaborating. Turns out, her timing was great. The academy was already in conversation with the S.D. Bechtel Jr. Foundation, which was eager to fund just such a citizen science program. While the MMWD runs the project on the ground, the academy provides a permanent home for the plant specimens (known as an herbarium) and botanical expertise.

Even though Mount Tam has drawn botanists for more than a century and many of them have extensively studied and collected entire families of species, no one has endeavored to make a complete collection of the mountain’s plants. It’s an important project, given that over the next 100 years the effects of climate change (higher temperatures, changed precipitation patterns, etc.) are likely to impact the botanical mix. Already, the suppression of fire and introduction of nonnative species have altered the species composition as compared to several hundred years ago.

“Fire suppression has been introduced to the mountain since the 1800s, which means it is losing open meadows” and perhaps some of the plants that thrive in them, says Alison Young, the citizen science engagement coordinator for the academy. “In the higher elevations, there might be plants that are no longer there because of warming.” Without a baseline, it’s difficult to know which plants are gone and which have moved in; this project will make it easier to track such changes.

The program began with Williams, Young, and MMWD volunteer coordinator Suzanne Whelan organizing five to six “bioblitzes” each year. These involved roping off 30-foot-diameter sections of the mountain’s woodlands, grasslands, chaparral, and wetlands, then deploying teams of citizen scientists to identify every type of plant inside, collecting one flowering or fruiting specimen of each species. By 2015, bioblitzes had found 600 specimens, which were logged into iNaturalist, an online identification resource (and smartphone app). But when it became clear the bioblitzes were not turning up many species to check off the list, the water district launched the plant safaris—where plant-savvy volunteers team up with expert botanists once or twice a month to search for the most elusive species.

Even before we find the hairy bird’s beak, all signs point to a good day of plant hunting. Two minutes onto the trail Williams finds a flowering Bromus, a type of native grass. But is it Bromus hordeaceous, as she suspects, or something else?

Brostrom leafs through Jepson. “The teeth are generally not translucent,” he calls out, scanning the manual’s description. The sun is already fierce and beads of sweat are rolling down his cheek. “Is the lemma papery or leathery?” he asks. I silently ask myself, “What the heck is a lemma and how would I know if it’s papery or leathery? Also, grasses have teeth?”

But Brostrom knows what he’s doing. For his day job, he sets and inspects traps for Alameda County, looking for the crop-destroying Mediterranean fruit fly. But off-duty he’s a seasoned botanist, involved in this project since its inception, and one of 189 committed citizen science volunteers who have contributed more than 3,600 hours in the bioblitzes and safaris. Later, when we head to MMWD headquarters to log our haul along with five other safari teams, Brostrom points out Doreen Smith, one of a handful of experts on another safari team that day: “She is probably the top botanist in Marin County,” he says.

With my lack of botanical acumen I am named team photographer; for each new plant we collect, I snap a few shots of its leaves, flowers, stems, and root. My teammate Robin Truitt is tasked with filling out each plant identification sheet. “It’s like taking a college course without having to pay tuition,” she says as we eat lunch in the shade of tall live oaks along Alpine Lake. A former National Park Service ranger, she joined this project partly to get better acquainted with the wealth of public land within the MMWD, including 150 miles of trails and fire roads: “I’ve lived in Marin County 20 years and I’ve never been on this trail before.”

As we scan a flat, dry section just uphill from Bullfrog Creek, Williams spots another plant she’s been hunting: Dianthus armeria ssp. armeria, or grass pink. (While it’s a non-native, the objective of the safaris is to document all species.) It’s an unusual find—the first instance of this plant in the whole of Marin County, as far as Williams knows. She easily distinguishes it from the large cluster of Centaurium erythraea just inches away. To me, they look virtually identical. “The Centaurium has yellow reproductive parts,” she tells me, pointing to the small flower and comparing its smooth petals to the jagged edges and telltale white pattern on the Dianthus. It’s amazing what a trained eye can see.

Nearly two-thirds as large as the landmass of San Francisco, the lands owned by MMWD would be a bear to manage even if they did not supply drinking water for 186,000 customers in central and southern Marin. Directing trail users—keeping hikers from swimming in the enticing lakes and dissuading mountain bikers from riding outside of marked trails—makes it even harder. But Whelan sees her job as a good way to promote appreciation of these public lands by the people who use them. “It’s good to have an educated constituency,” she says.

Count me as one of those constituents. By day’s end the five safari teams have collected 26 plant specimens, among them a hard-to-find wetland species and a handful of species that are rare in Marin. We’ve brought the baseline a step closer to completion, and the hours we spent baking in the sun-exposed grasslands and dodging poison oak in the steep ravines were well worth it.

To participate in MMWD citizen science projects, visit marinwater.org/193/Citizen-Science.

Bay Nature subsequently learned that Cordylanthus pilosus was recorded on Mt. Tam in 1994 and 2010, according to Calflora.