Lost Worlds of the San Francisco Bay Area, published by Heyday, is a coffee table book of vignettes by author Sylvia Linsteadt. Each essay is researched but also an act of historical imagination. This is an excerpt about the history of coal mining in the East Bay. Click here to read another excerpt about the logging of the East Bay’s giant redwoods. Today both areas are parks, protected and restored by the East Bay Regional Park District and open to the public.

It is hard to imagine what the miners felt when they came up out of the heart of Mount Diablo at dusk. It is hard to imagine the kind of darkness they held their small candles and oil lamps to all day, or the weight of so much mountain above their heads. Humans are not meant to spend a day—let alone days, year after year—deep underground. Emerging into the soft breeze above ground at the end of each shift must have been a very sweet and simple kind of miracle.

Coal was discovered beneath the northern flanks of Mount Diablo in 1859 when a local rancher struck a vein while cleaning out one of his springs, and disgruntled argonauts weary of gold panning flocked to the site, ready to make a steadier profit by this dark treasure. Family after family followed, not only old gold rush diggers, but immigrants seeking work from all over the world—Wales and Italy, Germany, China, Scotland and Australia, Mexico, Canada, Austria. They planted trees from their home countries—black locust, cypress, tree of heaven, pepper tree—like prayers: that they too might grow roots and branches and flourish here where it was dry, here where at night the sky was huge and speckled and strange and the coyotes howled.

Five towns were sparked into existence by the mountain’s coal, growing up quick as flame around the three seams on Mount Diablo’s foothills. The towns were Nortonville, Somersville, Judsonville, Stewartville, and West Hartley, all stark against the steep, dusty hills. They clustered in separate valleys around the coalfields, though each was within easy walking distance of the next on footpaths and narrow roads that led up and over the dry hills. Nortonville was the largest (with nine hundred residents by 1870) and the most centrally located of the five, with Somersville next beyond the eastern ridge. Stewartsville lay further east beyond Somersville, and the smallest two settlements, Judsonville and West Hartley, were built all the way at the furthest eastern edge of the mines. It must have seemed, to the chamise and sagebrush and manzanita that grew on the ridges, as though the five mining towns were slapped up overnight. One day dry hills, the next day clapboard butcher’s shop, boardinghouse, post office, a dozen little Victorian cottages with sapling trees from around the world, growing fast. By a count taken on February 26, 1870, 315 men worked the veins in the Mount Diablo coalfields, from coal cutters and miners to engineers, underground foremen to minecart drivers and furnace men. There were twelve mines total, accessed by steep shafts and tunnels, and centered around three primary veins: Clark, Little, and Black Diamond.

Despite the darkness that the miners endured day after day digging coal inside the mountain, there was a lively brightness to the towns that belied the grim reality underground. Walking home down the mountain, swinging their round lunch pails and stretching in the gentle evening, the men might have caught a whiff of baking bread—fourteen loaves twice a week!—made by Amelia Ginichio at her family’s boardinghouse on Italian Hill. Or they might have glimpsed the white horse named Jim making his rounds throughout Nortonville with grocer and cart to drop off food and supplies requested in the morning. Maybe, going their separate ways on paths through the foothills, some of them were passed by a speeding horse and cart—midwife Sarah Norton inside—rushing off to attend a birth. In the course of her life, the wife of Nortonville’s founder was said to have delivered six hundred babies without losing a single one.

Down in the towns there were barbershops in which to clean up, billiard saloons in which to unwind, and for those miners who wished to further their education, there were evening classes offered by local schools. Many men religiously attended these classes, even after a ten-hour day underground, especially those who had left school for the mines when they were only boys to help support their families. Fraternal organizations abounded, from the Sons of Temperance, the Masonic lodge, and the Grand Army of the Republic, to the Ancient Order of United Workmen. According to visitors, the Mount Diablo coal towns were positively lively; Somersville boasted two excellent hotels with room for up to one hundred boarders, several stores, and a billiard saloon, not to mention a very good public school system. And for all the men working underground, there were nearly as many wives, daughters, or mothers working above ground. Women ran suffrage societies and worked as postmistresses, schoolteachers, and hotel proprietors, not to mention the daily work of tending house, garden, and livestock.

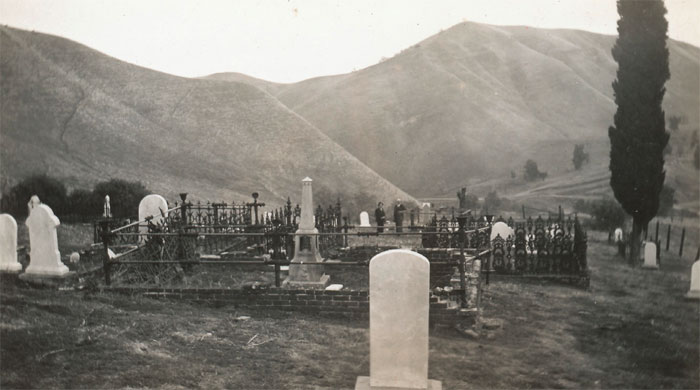

For those with loved ones in the mines, no doubt this daily work was often accompanied by a small prayer—that another dusk would arrive without incident underground. There were periodic tunnel cave-ins, as earth and stone collapsed without warning in great sighs of mountain weight. Sometimes, loose coal dust was ignited by a spark or candle flame, causing devastating explosions, or carts loaded with coal snapped their ropes, crushing whoever happened to be behind them. The insides of mines are laced with sudden seeps of deadly gas (called damps by miners: firedamp, blackdamp, whitedamp, stinkdamp, after-damp), which cause asphyxiation, explosions, or both. Miners were equipped with flame safety lamps, which served as both light and warning signal, but according to a report in an 1874 edition of the Contra Costa Gazette, the light was feeble compared to other lamps that the men used, and many were willing to risk their lives rather than bother with the inconvenience and unease of poor light far down inside the earth. Many preferred the simplicity of a candlestick inside a can (called a bug light), or an oil wick lamp affixed to the front of a cap. The Rose Hill Cemetery attests to the danger of work in the mines, as most of the burials are either of young men—such as the eleven lost in an 1876 explosion caused when loose coal dust was ignited by a seep of methane four hundred feet deep in the mines. Otherwise, most of the graves belong to babies lost to childhood illnesses.

Still, work was work, and Mount Diablo’s young, subbituminous coal was abundant, occurring in great, dark layers, so that from the 1860s to the early 1900s, four million tons were hauled up to the light and burned in Northern California. Mount Diablo coal lit the woodstove of virtually every home throughout the Bay Area, warming the feet of mining investors and dairy lords, prostitutes and laborers and bakers alike. Every factory, steamship, ferry, and mill around ran on the stuff too. By the 1870s, trains came and went daily, crossing five miles each way on tracks as straight as an engineer’s ruler, from the foothills of Mount Diablo to the banks of the San Joaquin River delta.

Less than fifty years after the first coal was dug, the towns and coal mines were virtually empty. A flash of digging, dancing, praying, loving, and striving over barely two generations—and then nothing. Families followed the coal, and a new mountain far up north in Washington provided a finer, bituminous variety. The Columbia Steel Corporation discovered silica near Nortonville in the 1920s, and started mining the deep, thick sandstone beds for foundry sand. Soon enough, glass-worthy silica was uncovered near Somersville, and by the 1930s, the Hazel-Atlas Glass Company was shipping the raw minerals for glassware to their Oakland bottle-making factory. Still, the towns were never fully occupied again, and far below, deep down in the heart of the mountain, the coal remains, untroubled by human hands.

We are playing with fire when we dig out the hearts of mountains. We are playing with fate, with faulty lanterns held aloft. But people being people, there will always be dancing between, and dozens of loaves of fresh bread.

.jpg)

-300x225.jpg)

-283x300.jpg)