To examine the white bud pads of the western leatherwood plant, Iowa State professor of horticulture William Graves once wrote, is “almost like staring into a starry night sky.”

It’s a rare celestial vision, though. The winter-blooming shrub’s entire global range is confined to six counties in the Bay Area, including the Huckleberry Botanic Regional Preserve in the East Bay Hills. Thanks to the preserve’s interpretive trail, the western leatherwood is easier to see growing wild here than maybe anywhere else on the planet, along with a handful of other uniquely Californian plants. This winter, just as the leatherwood began to bloom, I hiked the preserve to find some of its stars.

Rare plants are, ironically, not uncommon in California. We’re in one of the world’s botanical biodiversity hot spots, and so many of the state’s plants are adapted to confined geographic locations (among other rarity-inducing factors) that the California Native Plant Society estimates about 20 percent of the state’s native flora is rare or endangered. California botanist and explorer Lester Rowntree, an early advocate for California’s plants, wrote that “it is this wide variation of climate and terrain which for the past two or three decades has inspired in me—at first intermittently and at last with dogged persistence—a passion for observing, each in its own place, the natural plant life of these diversified regions.”

Some of these regions, like the coastal old-growth redwood forests and the spring wildflower displays of the Carrizo Plain, are well known and widely treasured. Others, like the maritime chaparral of Huckleberry, are subtler. Maritime chaparral is adapted to the cool temperatures, moisture, and fog characteristic of marine-influenced climates. Because Huckleberry sits on a northeast-facing slope in the direct path of sea breezes blowing through the Golden Gate, the conditions are opportune for this rare ecosystem.

The first morning I hike Huckleberry the air is crisp and the ground is still moist from recent rains. Landscape architect Sherri Osaka joins me to help find some of the plant highlights and offer her perspective on them as a designer. We start the walk by winding along a northeast-facing slope as we drop 200 feet into the San Leandro Creek basin, where steam rises over a verdant canopy of California bay, coast live oak, Pacific madrone, and California hazelnut. Along the trail Osaka points out a handful of California natives that are familiar parts of both designed and wild landscapes: pink-flowering currant, western sword fern, and California huckleberry. Even in a dry year, “everything is surprisingly lush and green here,” Osaka says.

As we pass an exposed outcrop, I run my hand over the damp crumbling layers of rocks, releasing a sweet, earthy smell. The jagged texture of the rocks is interrupted by the soft forms of green moss mounds. Goldback ferns cling to the vertical surfaces, their roots extending into rock fractures, widening these with each passing season. The almost imperceptible daily erosion of the rock surface by roots, rain, and weathering results in massive changes on the geologic timescale. As I pull my hand away a small sharp fragment breaks off, landing on the pile below, hinting at this ancient process.

Although the stars of Huckleberry are its rare plants, the firmament that makes it all possible is an unusual rock pattern. Huckleberry’s ridges and rock walls are made of chert and siliceous shale uplifted from ancient seafloors, both of which create soils low in nutrients that make it difficult for many plants—particularly weedy nonnatives—to figure out. Michele Hammond, a botanist with the East Bay Regional Park District, says the pale soil in the chaparral areas at Huckleberry is comparatively free of the invasive plant species that clog up many other open spaces in the Bay Area. But California plants adapted to unique soils and fog thrive here.

The first time she, as a botany student, saw the park, Hammond says, “I was amazed and surprised at the diversity of plants along this trail. We were using the Jepson Manual to key out species and as you walk through the oak woodland and into the upper loop chaparral sections there is a lot to see, making it stand out among East Bay locations.”

After about a mile of following the creek, Huckleberry Loop Trail doubles back toward the hill and climbs sharply. Osaka and I hike up out of the dense bay forest into an oak-bay woodland. We detour onto a spur trail that leads us to a “manzanita barren,” an exposed, rocky outcropping, where we warm up under the bright sun and can see the canyon below and Mount Diablo in the distance.

Manzanitas, with their smooth bark and striking sculptural forms, have garnered attention from gardeners and botanists alike. “Few native plant groups are as symbolic of the California landscape as the manzanitas,” horticulturist Nevin Smith wrote in Native Treasures, his 2006 California native gardening handbook. The California Floristic Province (which spans most of the state) is home to more than 100 manzanita species and subspecies, with an incredible diversity of shapes and sizes ranging from low sprawling ground covers to plants reaching the height of small trees. Manzanitas readily adapt to demanding, site-specific conditions, evolving into species that exist only in limited areas. One of the rarest and its cousin grow in Huckleberry: pallid manzanita and brittleleaf manzanita, both flowering in profusion on our visit.

The two species typically grow near each other and can look similar, but the rare pallid tends to have almost heart-shaped, grayer leaves, with lobes that appear to clasp the branch. And at the base of a brittleleaf sits a lumpy, woody mass known as a burl. Dormant inside the burl are densely packed buds waiting to sprout in the wake of a fire that burns off the shrub’s upper branches. It’s a survival strategy that means a burl can be both very old and correspondingly slow to adapt to change. Pallids, on the other hand, resprout from seeds, and the seedlings either thrive or die in their environment. Manzanita seeds can lie dormant for long periods waiting for the heat of fire and chemicals found in smoke to trigger their germination.

As we step into the center of the barren, we hear the electric wingbeats of Anna’s hummingbirds. They are making short, sharp calls from bushes and shrubs in every direction, their bright red throat feathers catching the sunlight. Flying high into the air, some chase each other before diving back down. Hammond describes the pallid manzanita and its white blossoms as “particularly beautiful when it is flowering because it is covered with butterflies and hummingbirds.” Manzanitas provide pollinators with an important midwinter source of nectar. California natives flower year-round in a profusion of sizes, shapes, and colors that enable pollinators to stick around, too, one of many reasons the rich native plant diversity at Huckleberry, and elsewhere, matters.

Farther along the main trail we encounter a second spur; this one takes us past a western leatherwood , its flexible branches reaching up hopefully, though no star-buds yet. If the buds caught Graves’ attention, then the shrub’s cascade of stamens and yellow February blooms may have been what inspired the plant’s original namer. Its genus, Dirca, is derived from a Greek myth’s spring and references an ancient fountain near Thebes. Discovered in the “mountains near Oakland” by J. M. Bigelow in 1853, this species has likely been in North America for tens of millions of years.

A hundred yards or so beyond the spur, we’re surrounded by the park’s maritime chaparral—a thicket of manzanita, golden chinquapin, jimbrush, coast silk tassel, pink-flowering currant, and toyon. A common plant found throughout the preserve and along the trail is the evergreen huckleberry , a shrub that produces glossy purple-black berries every fall and accounts for the park’s name. The edible berries have long been enjoyed by people; in the preserve, the birds and rodents rely on the berries. Native to coastal California, and in the East Bay found only in the Oakland-Berkeley hills, the huckleberry blooms with white-and-pink bell-shaped flowers in spring.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

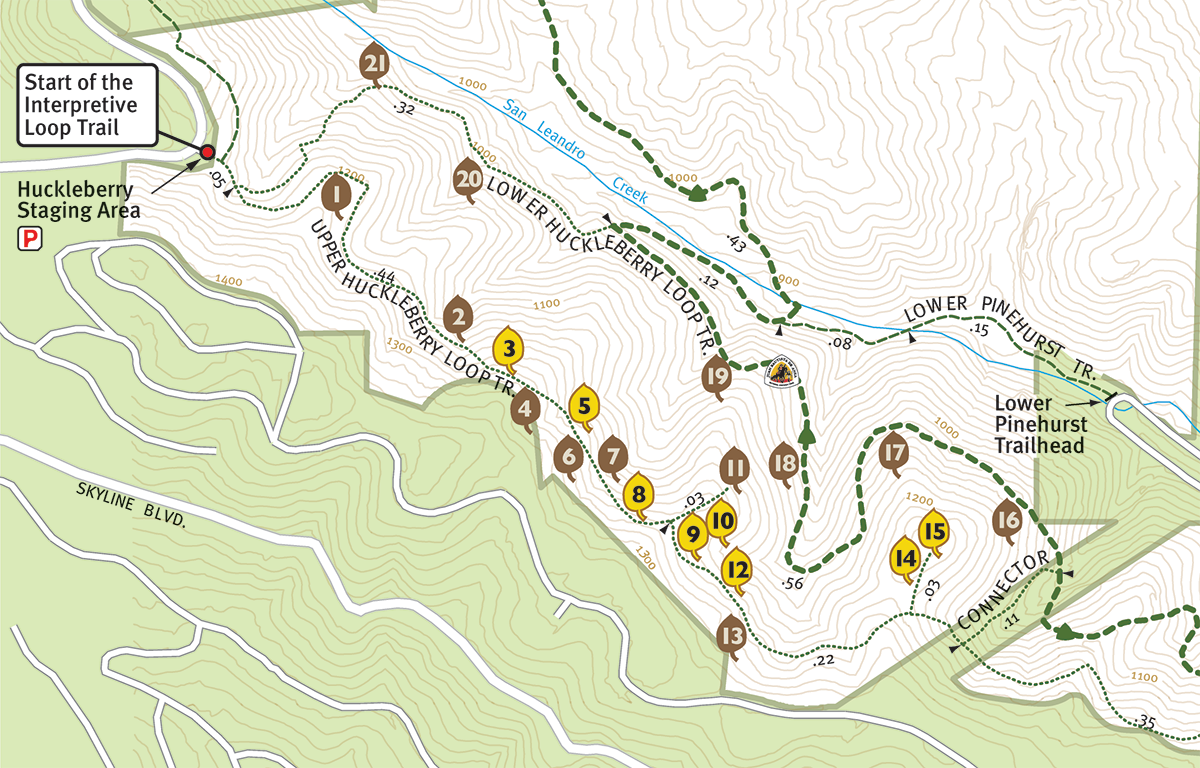

HIKING HUCKLEBERRY PRESERVE

Getting There: Huckleberry Botanic Regional Preserve is off Skyline Boulevard in Oakland. There’s a small paved parking lot, pit toilet, shady picnic table, water, and a map and brochures detailing the self-guided plant walk. Dogs, bicycles, and horses are prohibited in the preserve.

Trail: The Huckleberry Loop Trail — a 1.7-mile trail with an elevation change of 277 feet — loops around the 241-acre preserve through a mature California bay laurel forest on the lower trail and a swath of maritime chaparral on the upper trail. Thanks to a Habitat Conservation Fund grant, trail improvements and updated informational signs, installed in 2017, will lead visitors on a self-guided walking tour of the plants.

For a short, easy stroll that allows you to see many of the unique maritime chaparral species, head southeast on Upper Huckleberry Loop Trail and then turn back before reaching the connector trail.

Spring Flowers:

- Bee plant

- Evergreen huckleberry

- Snowberry

- Douglas iris

- Fringe cups

- Jimbrush

- Small-flower alumroot

- Woodlant tarplant

- Western columbine

Conservation and Restoration: Join volunteers who meet once a month with the East Bay chapter of the California Native Plant Society to remove invasive weeds from the preserve. For more information email sibley@ebparks.org or visit the group’s meetup page.

Huckleberry presents a challenge to the rare manzanita. Chaparral plant communities depend on fire for their health and rejuvenation, and without it huckleberries and other large shrub oaks, and ultimately bay laurels will naturally overtake and shade the manzanitas, creating conditions that eventually kill them. It’s a natural process called succession. But given the preserve’s proximity to houses and structures, fire suppression is necessary at Huckleberry, which also puts chaparral species at risk. Hammond explains that “now that humans have removed fire from the system, we need to think about other ways to help maritime chaparral continue to thrive.”

The park district is considering careful pruning or removing of competing plants, primarily nonnative invasive species, that shade out the manzanitas. Hammond also encourages folks to explore another park during rainy weather when soil from the trail can stick to shoes, to help prevent the spread of water molds in the genus Phytophthora, soilborne root-rotting pathogens that rapidly kill plants. In 2017 they were found to have infected some rare shrubs along the upper loop trail in Huckleberry, according to Hammond.

As Osaka and I leave the park, she recalls the shift, about a decade ago, when clients began to request California native plants in their landscape designs. It’s not hard, driving past the urban gardens of the Bay Area, to see those gardens someday playing host to maritime chaparral species.

Still, there’s something to the sensory overload of seeing all these rare plants together in the wild. A designer might convincingly pull some of those stars into a garden. But to walk through Huckleberry, to smell the earth and listen to the birds and admire the brilliant combination of botanical texture and color and architecture that reflect natural California’s unique character, is to get a sense of the cosmos.