Once a week, Anastasia Ennis gets up before sunrise breaks and tide rises and travels to the North Bay marshes with biologists from several State and National wildlife agencies to check their traps for one of the Bay Area’s most charismatic micro-mammals, the salt marsh harvest mouse.

If a mouse finds its way into the non-lethal traps, the biologists will measure, note, and mark it with an eye to answering some basic questions: How many salt marsh harvest mice are there? How are they doing? What’s the best way to manage its degraded habitat?

Ennis, a second-year graduate student at San Francisco State, has similar questions, but a unique approach. Before each mouse is released back into its wet and wild home, she plucks a little bit of cinnamon-brown fur from the base of its tail and plops it into a vial with alcohol. Then she takes it back to the genetics lab.

Although many people are studying salt marsh harvest mice, or “salties,” as they are affectionately known, Ennis is one of a few people studying harvest mouse population genetics. And the research she is now conducting, when paired with traditional trapping surveys, may yield information that will help inform management and conservation decisions for the secretive mice and their habitat.

Ennis is looking at two special genes that all higher vertebrates (including people), share. Part of a group of genes called the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), they code for proteins found on the surfaces of cells that help the immune system recognize and fight off intruder cells, such as bacteria or viruses. In general, the more variable the genes at the MHC are, the better the health and resiliency of a population.

“In a conservation context, more variation at the MHC means the mice are better able to adapt to changing conditions,” Ennis said. “When designing new habitat and habitat corridors with an endangered species in mind, you generally want to maximize genetic diversity — especially when population numbers are low.”

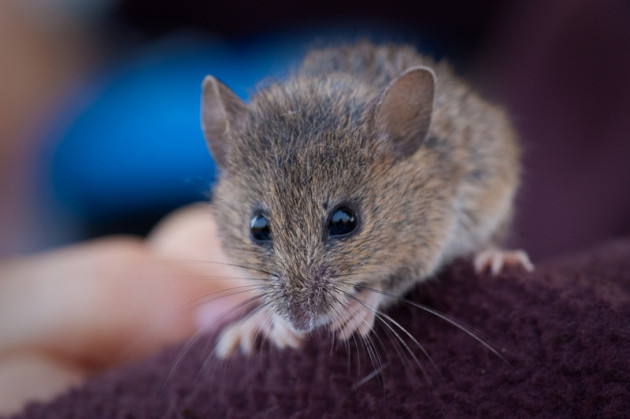

At three inches long, salt marsh harvest mice are one of the smallest mammals in Unites States, with sparkly (and according to the cuteness index, adorable), beady eyes. But they are tough too. Their ability to swim and climb to safety at high tide, and to tolerate high levels of salt in their food and water, makes them uniquely well-adapted for life in salt marshes. In fact, they are the only mammal species in the world endemic to tidal marshes.

The diminutive rodents once scampered through the salt marshes that ring San Francisco Bay, from Palo Alto to Suisun Bay, up the Petaluma River, west to the Marin peninsula and into the eastward arms of the Delta. Today they inhabit smaller and more isolated pockets of habitat, largely due to human activities such as development at the perimeter of the Bay. The habitat that does remain often lacks the upland marsh the mice need to escape the highest of high tides, their favorite food – pickleweed — and the essential vegetation cover they need to hide from predators.

With 84 percent of the original salt marshes in San Francisco Bay now lost, it’s no surprise that salt marsh harvest mice have been on the endangered species list since 1971. But how many are there? Nobody is quite sure. Counting mice in a marsh is as difficult as it sounds — they aren’t exactly lions on the Serengetti. The quiet mice hide in dense brush during the day, venturing out under the soft fuzzy light of the moon.

In situations like this, biologists generally trap a sample of the population, mark and release them, then trap another sample later. Because the proportion of marked animals in the second sample should reflect the proportion of animals marked in the entire population, counting the number of marked individuals within the second sample gives an estimate of the population density – or how many animals there are in a given area. That’s not quite the same as the total number of individuals in a population, but it’s a useful average. These so-called mark-recapture surveys have been performed in some places, such as Suisun Bay, where large stretches of wetlands remain relatively intact, and the land is managed for waterfowl and recreation so the possible environmental impact on the mice must be taken into account.

But trapping is very labor intensive and can be imprecise. To get a reliable estimate, trappers have to return to the same site multiple times a year. The more mice sampled, the more accurate their population density estimates will be, but time and funding are often limited. And just for a little extra fun, salt marsh harvest mice look an awful lot like western harvest mice, and can be very hard to tell apart in the field.

“Error rates are high for mark/recapture studies, which is why folks are reluctant to give population estimates,” Ennis said.

But pairing genetics with the trapping studies can help Ennis identify the mice to species. And based on the genetic diversity she sees at the MHC she will be able to infer how many breeding individuals there are in a population and how well the populations are moving in and between their fragmented habitat.

If she finds low genetic diversity it would be a worrying — but not entirely unexpected – result. It might suggest management by creating corridors to bring isolated populations into contact and maximize gene flow. But if the diversity is unique in salt marsh harvest mice from different areas, it could be an indication that the isolated populations have become locally adapted to their particular environment — in which case it might be important to continue keeping the populations separate.

“It’s complicated,” Ennis said. “But I believe that with more genetic information available for these populations, managers will be able to make more informed decisions about how to best design habitat restoration projects with the mice in mind.”

For now, Ennis has been mainly sampling mice in the North Bay — including Suisun Marsh — because there is more funding for California Department of Fish and Wildlife and US Fish and Wildlife Service biologists, who she tags along with, to do trapping up there. On a good night, in a relatively large marsh, they can catch 15-30 mice. In smaller, newly restored marshes like those in the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge, where they don’t have room to set up as many traps, they sometimes catch less than 10.

Ennis said she hopes to collect more samples from mice in the South Bay this season, where most marshes lack critical upland habitat and information on population size is particularly lacking, and hopes to publish her findings in the latter half of 2015.