We’re standing in a sanctuary that nearly didn’t happen. A paradise almost lost.

This lush green meadow in the Coyote Valley, which runs north-south along Coyote Creek from San Jose down to Morgan Hill, has been targeted for residential and commercial development several times since the 1970s.

But the tech industry’s ups and downs have been this landscape’s salvation, as a series of economic downturns delayed development and created opportunities for the conservation community to buy and protect this precious property.

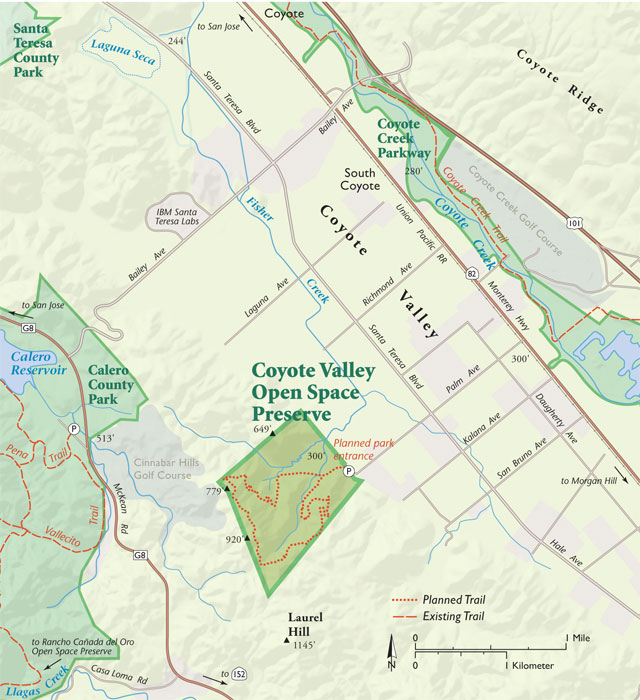

So our hike today is not on asphalt but instead along a new trail up to splendid views in the brand-new Coyote Valley Open Space Preserve, a 348-acre rolling expanse of hills, oak trees, and serpentine outcroppings—all just a short bus ride away from a city of one million that’s a national symbol of suburban sprawl.

“Perfect timing. This could have been tract homes,” says Derek Neumann, a field operations manager at the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority, which purchased the property five years ago. “It was going to be one- to two-acre home sites.”

In summer 2015 the park’s two loop trails will be completed and the former ranch will open its gates to the public. One trail, three miles long, ascends a ridge to picnic tables and sweeping views of the South Bay. The second is a mile-long perimeter trail around the 26-acre meadow—perfect for anyone looking for a short, scenic, relatively flat walk.

It’s no surprise that much of the Bay Area’s public open space is found in the hills, where development pressures aren’t as strong as in the valleys. That makes the new Coyote Valley preserve all the more valuable. “This is one of the few places where the public has access to the actual valley floor, not just the hillsides. That was critical to us,” Neumann says.

The preserve also protects one corner of Coyote Valley’s critical habitat here at the southern narrowing of the broad Santa Clara Valley. And it represents another step toward a trail connecting 10 county and regional parks in the heavily populated South Bay—from Lexington Reservoir near Los Gatos to this Coyote Valley parcel, spanning a distance of 15 miles.

In springtime the landscape seems almost ebullient. The sun strengthens, the air warms, and great billowy clouds sail over the valley like a caravan of tall ships. Insects fill the air and wildflowers appear in these pastures, still grazed by a small herd of Black Angus. “This whole area turns into a carpet of yellows and golds and oranges and whites,” says Matt Freeman, assistant general manager of the Open Space Authority. Peak bloom usually comes in mid- or late April.

We’re flanked by two outcroppings of serpentinite, a metamorphic rock that produces soils with high concentrations of iron, magnesium, and other minerals that are toxic to many plants. But a number of native California plants have adapted to this nutrient-poor soil, including the only two plants eaten by the larvae of the threatened bay checkerspot butterfly—California plantain and owl’s clover—which have found a home in the preserve. The checkerspots’ greatest stronghold is just across the valley on Coyote Ridge, and while the rare butterflies are still unusual in the acreage of the new preserve, protection and restoration of these outcroppings could provide additional habitat, and help expand their range, says Stuart Weiss, chief scientist at the Creekside Center for Earth Observation and a leading expert on the checkerspot.

Other unique wildflowers of these serpentine rocks include the rare Santa Clara Valley dudleya. “It is a hotbed of diversity,” Weiss says. “A remnant valley oak savannah, with beautiful blue oak woodlands and then serpentine grasslands on rocky outcrops.”

From a nearby field, a harrier keeps a watchful eye. A pair of magpies, pretty much at the western extent of their range, exchange a harsh, chattering “wock-a-wock, weer, weer” as they fly between valley oaks. In the distance to the east, commuters race by on Highway 101.

The commuters are a big part of the story here in the fastest-growing county in the Bay Area, with a population projected to increase by 36 percent—another 700,000 residents—by 2040. In 2001, the Coyote Valley was named a Last Chance Landscape, one of the 10 most endangered landscapes in the nation, by Scenic America, a nonprofit group in Washington, D.C., whose goal is to preserve the scenic character of communities.

For Neumann, the place is a reminder of the agricultural center the big valley once was. He’s watched as the fields and orchards of his childhood were transformed into endless suburbs, factories, parking lots, shopping centers, freeways, and cloverleaf exchanges and he marvels at the rapid rate of change.

“I grew up in San Jose back in the day, when Highway 101 was only two lanes, in either direction,” he recalls. “There were orchards in the valley. We’d pick crops when farmers wanted help, and sometimes when they didn’t,” he laughs. “Those were the days.”

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

GETTING THERE

Coyote Valley Open Space Preserve opened in summer 2015. From most of the Bay Area, take Highway 101 south past central San Jose. Exit Bailey Ave; turn right on Bailey, left on Santa Teresa Blvd, and left on Palm Ave. A paved parking lot, with turnaround for horse trailers, is at the end of Palm Ave. Bathroom facilities on site. For details on trail conditions check with the Santa Clara County Open Space Authority: openspaceauthority.org/.

To get a view of some of what’s been lost—and saved—we climb out of the meadow toward the park’s best view: a rocky perch on the southern ridgeline, overlooking the trough of the wide Santa Clara and narrower Coyote valleys.

The trail takes us under a canopy of blue oaks, which thrive in these lean and dry soils. We smell fragrant California bay laurels and step over California buckeye seeds, looking polished and lacquered. We startle a pair of deer, who bolt into the woods.

It was on a trail like this that Neumann first fell in love with the outdoors. He was in eighth grade, just another suburban kid from San Jose, on a school field trip. “I still remember that, to this day, 30 years later,” he says. “If I can do that same thing for one person, I have really succeeded. If I can do that for a whole host of people? Wow. What a legacy to leave.”

Now he oversees construction of trails—“an art and a science,” he says—on several Open Space Authority properties. His team studies maps to learn the contours, elevations, and presence of any fragile species. They chart six or seven potential routes, taking care to keep the grade at an average of five to six degrees, never exceeding 12 percent. Each route is assessed for landslide risk and tagged with flags. To prevent erosion, Neumann has learned to build small retaining walls rather than carve into the hillside and gently “outslopes” the path, so water won’t puddle. “A lot of trail-building is about ‘feel,’” he says. “I ask myself, ‘Does this feel right? Does it have enough swooping curves to it?’”

Checking out Neumann’s handiwork, we climb out of the woods and emerge onto a vantage point on a windswept knoll, along the edge of a razorback ridge overlooking the South Bay. Immediately below is a view of the entire 7,400-acre Coyote Valley. Beyond, to the east, is the 4,000-foot massif of Mount Hamilton, crowned by the University of California’s Lick Observatory. To our west, we see the white ball of the National Weather Service’s Doppler radar, on the shoulder of Mount Umunhum. Oak-studded hills roll off along to the southern horizon, beyond Gilroy.

Standing here, we can see the landscape through geologic time. We look down on what geologists call the Santa Clara Basin, a broad, flat alluvial plain which for the past 1.5 million years has been accumulating water and sediment from the Santa Cruz Mountains to the west and the Diablo Range to the east. It is bounded by restless faults: the San Andreas Fault on the southwest and the Hayward and Calaveras faults on the northeast. Coyote Creek has its origins above this basin, in a smaller eroded valley created by the incessant grinding of rocks along the Calaveras fault.

We visualize the ancestral winter storms that washed rich soils from these hills, rinsing them into the valley’s Fisher and Coyote creeks corridor. The meadow below us was likely once a wetland, home to reeds and willows, and is still a site of frequent flooding. (The Laguna Seca, a seasonal wetland a half-mile beyond the gates of the new preserve, still draws hundreds of birds, including long-billed curlews, ferruginous hawks, the occasional bald eagle, and flocks of tricolored blackbirds, the latter a once-common visitor whose population has plummeted in recent years.) For millennia, wildlife has used this valley to travel both north-south and, more important, east-west between the large wildlife reservoirs of the Santa Cruz and Diablo Range mountains. So as the concrete of the Santa Clara Valley has filled in around it, the new preserve remains the edge of a critical modern wildlife corridor, where mountain lions, bobcats, deer, coyotes, and badgers can gather to head east across the valley and up into the Diablo Range, or complete their crossing of the valley and disperse again to the west.

Not all of the human footprint here is concrete, though. From our perch 700 feet above the valley floor, we admire the geometry of what remains of the valley’s agricultural heritage: pastures, row crops, greenhouses, barns, and an old picket fence line. This landscape, once dubbed the Valley of Heart’s Delight, was among the most productive farming areas in the nation, producing plums, apricots, cherries, walnuts, garlic, hay, and more.

We gaze north at distant subdivisions and the big white rectangles of Metcalf Energy Center, producing power for San Jose and the tech industry that began after World War II, triggering the housing boom that continues to this day. The valley air is stained by brown haze—toxic gases and particulate matter emitted by vehicles. But directly above us, where the air is clear, a golden eagle and two turkey vultures wheel on thermals.

As the tech industry burgeoned and Silicon Valley expanded southward, the peaceful Coyote Valley became the South Bay’s last undeveloped frontier. Tandem Computers eyed it as a site for expansion. Then Apple Computer made plans. More recently, Cisco Systems had visions of a sprawling new campus. Land developers, high-tech businesses, construction firms, and politicians hatched plans for a mini-city of 75,000 people—bigger than San Rafael, Walnut Creek, or Mountain View. This small parcel where we’re standing now, ranched by the Tilton family since 1917, was part of that urban high-tech dream. “My grandmother sold it to developers in 1993 so she could cover inheritance taxes,” says Janet Burback, who now runs her family’s 2,700-acre Tilton Ranch, adjacent to the preserve. “Before then we had the land in oat hay and cattle.”

But before the property could be developed Silicon Valley’s bubble burst—not just once, but twice. Home values plunged. The troubled economy, uncertain housing market, and costly planning delays created too much downside for the developers. Taking advantage of the developers’ misfortunes to save a piece of the valley floor, the Open Space Authority negotiated a $3.48 million deal for these 348 acres—a bargain for property that could have commanded up to $1 million an acre if sold for residential housing. “The economic pressure came off,” Neumann says. “The property owners decided to sell to us, rather than holding and waiting for development potential.”

Now the property has a new mission: hiking, outdoor education, a wildlife corridor, and agricultural rights, which are leased to Tilton Ranch for grazing. “I like the fact that it’s not developed,” says Burback, who will run 30 Black Angus cattle on the land once owned by her grandmother. “If they keep their promise and maintain it with grazing leases they’ll be able to acquire more land, because ranchers will want to work with them.”

We reach the end of our trail, marked by a pile of rocks and rubble. It’s a reminder of how much is yet to be done. Soon a helicopter will land on this site, delivering 10,000 pounds of materials for the construction of five bridges. When complete, the trail will continue over swales and along a steep upper western ridge, then descend, in a series of graceful switchbacks, through woodlands before joining an old ranch road.

It will end where we began, in ankle-deep grass under the graceful canopies of valley oaks. Soon this will be the site of an outdoor education pavilion, with interpretive signs. In the next decade, it is hoped, the trail will go much farther, linking to other public parks so people—and animals—can take long excursions up mountains, across scenic ridgelines, and into redwood forests.

The day will come, Neumann predicts, when Silicon Valley’s development pressures will bear down on this stretch of Coyote Valley once again. Even now, standing in this serene meadow, we hear its distant menacing hum.

But this valley will not suffer that valley’s fate. Through luck, timing, and hard work, the Open Space Authority has found a way to keep one valley from destroying another. “The bulldozers stop here,” Neumann says.