Tom turns to Jake and raises his crown. Elsewhere, Jenny eyes her mother hen and emits a distinctive “Putt!”

Watch out, it’s hunting season.

As turkey naming convention goes, Jenny and Jake are juveniles. Tom is a globber—that is, an adult male turkey. And each fall, the gregarious Meleagris gallopavo frolic across California’s countryside in search of acorns and wild grasses.

If the young turks had more presence of mind, this year they’d be especially cautious. For the first time in 14 years, California hunters are allowed to take two (rather than one) turkeys in the fall hunting season, and they get an extra 16 days to do so, into early December.

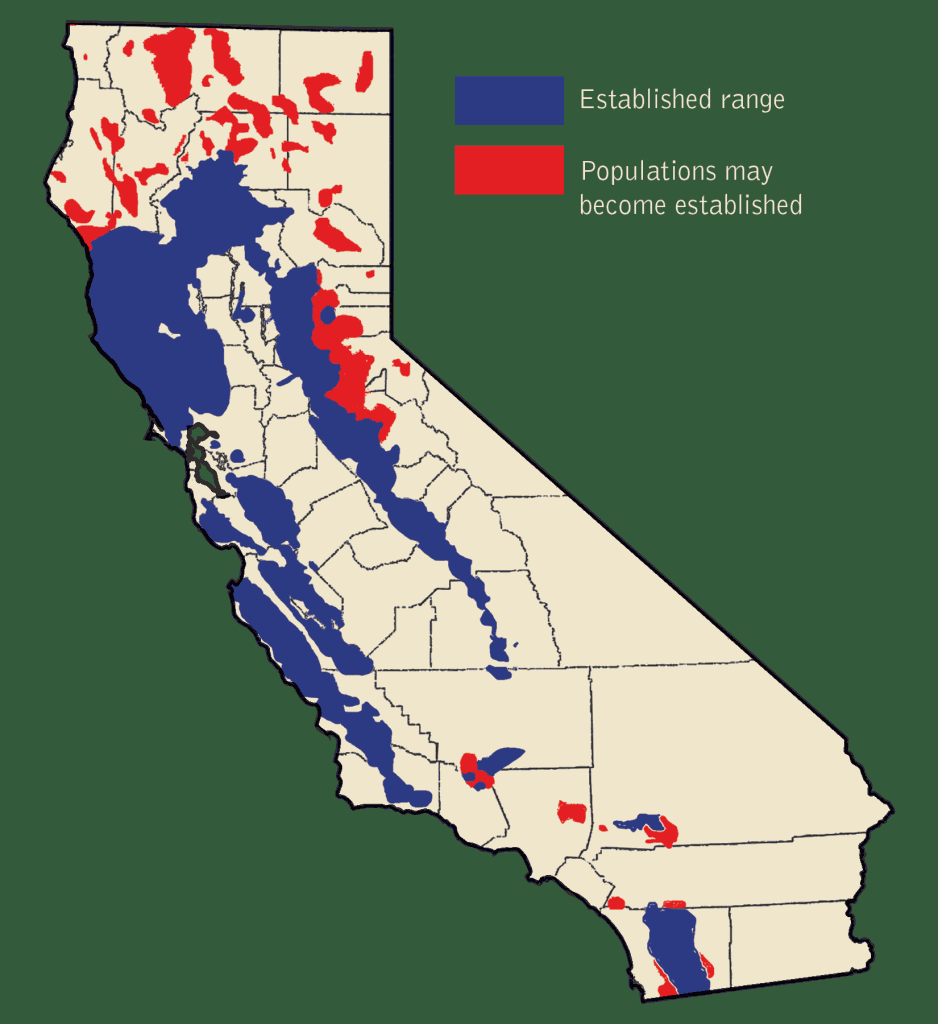

The California Department of Fish & Game made the change in response to a sizable growth in the population of wild turkey, a species first introduced to California in 1877 as game for hunters. Paradoxically, hunters are now seen as part of the solution to keeping wild turkey numbers in check.

Too many turkeys can be a stress on the local acorn crop and they can out-compete ground-nesting and grassland birds. They also make a nuisance of themselves by damaging gardens, defecating on sidewalks and harassing people for food. Wild turkeys can reach 20 pounds and become quite aggressive, occasionally even charging people.

Consequently, the number of nuisance cases has grown from few to many in recent years, especially in areas east and north of the San Francisco Bay as well as in the Sierra Nevada foothills.

The fall is the time when hunting can have the most impact on turkey populations. Trimming down the number of females before the breeding season means fewer chicks will eventually hatch.

But only the patient hunter can capitalize on fall hunting. Since food sources are widespread during November, turkeys roam vast areas of oak woodlands in search of a meal, which means locating rafters can be quite a challenge. (The spring hunt, on the other hand, coincides with the mating season, a time when Toms and hens are easy to lure with the lascivious calls of “clucks” and “gobbles.”)

Interestingly enough, outside of spring mating season, the bearded Toms stick with the Jakes and the Jennys with the hens. They exist in tight groups, segregated by family and sex and characterized by a strong pecking order.

The success of wild turkeys in California might come down to the fact that some 10,000 years ago, a turkey species existed here that potentially filled the ecological niche. Remnants of an extinct California turkey, Meleagris californica, have been found in the south, including Santa Barbara, Orange, and Los Angeles counties. More than 11,000 California turkey bones have been unearthed in the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits. It was smaller than today’s wild turkeys and had a wider, shorter beak, and it’s speculated that it went extinct because of climate changes in rainfall.

Turkeys say way more than just “gobble.” Here’s your guide to speaking wild turkey. Go here for audio recordings of their calls.

Putt: Watch out! Something dangerous is afoot.

Purr: I’m so happy.

Cluck: Hey, I’m talking to you.

Cackle: Hello, or goodbye,

Cutt: Come check this out!

Kee-kee run: Where are my peeps?

Gobble: Why, hello ladies.

Courtney Quirin is a Bay Nature editorial intern. Alison Hawkes, the online editor of Bay Nature, contributed to this story.

.jpg)

.jpg)