A few days ago, lepidopterist Liam O’Brien was sitting at the J-Church trolley stop at 18th Street and Church in San Francisco, admiring the Dolores Park construction, and his trained observer’s gaze rested on the above scene.

Yes: A hole filled with water! Plenty of explanations you could think of to account for that, to walk right by and not look twice.

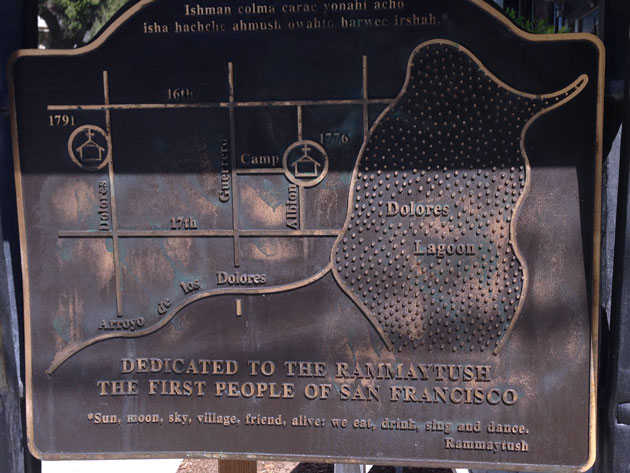

But O’Brien remembered something from the past. A plaque, somewhere in the Mission District, which he went looking for, and found here, a few blocks away at the corner of Camp and Albion Streets.

So maybe not just a hole filled with water. Maybe a bit of old, old San Francisco, poking through.

“They had excavated just low enough to reveal Lago de Los Dolores (Lake of the Sorrows) — the Dolores Lagoon, still there after all these centuries below the soil,” O’Brien wrote in an email post for Nature in the City.

The heroic persistence of our vestigial landscape, poking through just before Earth Day to remind us all that, no matter how many layers we add, nature is still there. Waiting.

There’s just one minor detail: What lake?

Christopher Richard retired from his role as curator of aquatic biology at the Oakland Museum of California and grew obsessed with the legend of Dolores Lake. “And legend,” he likes to say, “is not the same as scientific fact.”

He remembers the first time his co-investigator, consulting geologist Janet Sowers, saw the plaque. “She’s looking at that and saying, ‘I don’t see any way that could have been there,’” Richard says.

Based on the diaries of early San Franciscans, based on surveys and maps, based on the very geography of the land, Richard says, there wasn’t — couldn’t have been — a lake there. The plaque is wrong.

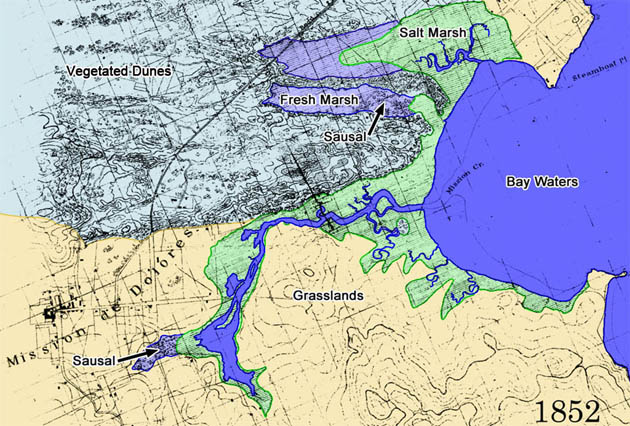

Here is Richard’s take on what the Mission and Potrero Hill areas would have looked like instead, based on a United States Coast Survey map from 1852:

The Mission is the black cluster on the left edge of the map. The early predecessor to Mission Street is the curved black line — a road of wood planks running off through the dunes to the north.

The main feature you see there, near-ish to the mission, is that blue water-looking thing. That’s not a lake, though — it’s an estuary, a place where tidal flows mix fresh and salt water. A tidal channel, fringed by marshes, wrapped around the north edge of Potrero Hill and then pooled somewhere around the modern San Francisco General Hospital. Wetland grasses grew along its edges, and a small willow grove — the “sausal” — clustered on its southern edge.

“Yeah, there was a body of water there,” Richard says. “But it was a tidal slough.”

The mission was supported by small creeks and springs — “ojos de agua o fuentes,” as Juan Bautista de Anza, the first Spaniard to visit the site labeled one of them. One of the creeks ran down what became 14th Street from the rocky outcropping where the old San Francisco Mint stands. Another ran down what became 18th Street, almost directly under the spot where O’Brien sat and photographed the Dolores Park excavation filled with water. San Francisco Recreation and Parks project manager Jacob Gilchrist wrote by email that he thought the water was those springs re-emerging.

So maybe it wasn’t a lost lake come to life. But it was a glimpse of the old way of the land pushing its way back into the modern world. And I’m not sure it loses any romance for brimming instead with long-buried ojos de agua.

“I gloried in this moment as the sun hit the water,” O’Brien wrote. “Some life forms, some amoebas sprang to life, soon to be buried again. Nature in the City.”