Every day, millions of people drive over it on a half dozen bridges. Ferries and freighters cross it. Windsurfers and kayakers and sailors ply its waters. It’s the picture-postcard backdrop for thousands of tourists along the San Francisco waterfront. And yet much of the real action in San Francisco Bay is hidden from us beneath murky waters.

Occasionally, we see some emissaries from the deep: sea lions haul out at Pier 39, seals bob in the water off Sausalito, pelicans and cormorants congregate over schooling fish or perch on posts. But, really, even scientists don’t know much about what’s happening down there, and where.

In contrast, if you’ve been walking along water much over the last decade, you might have noticed a lot happening around the Bay’s edges: ever-lengthening chunks of Bay Trail full of joggers and birdwatchers, increasing shoreline habitat at places like Heron’s Head Park and Crissy Field, and massive marshland restoration efforts in the South Bay and Napa, where former salt ponds are being transformed into marshlands.

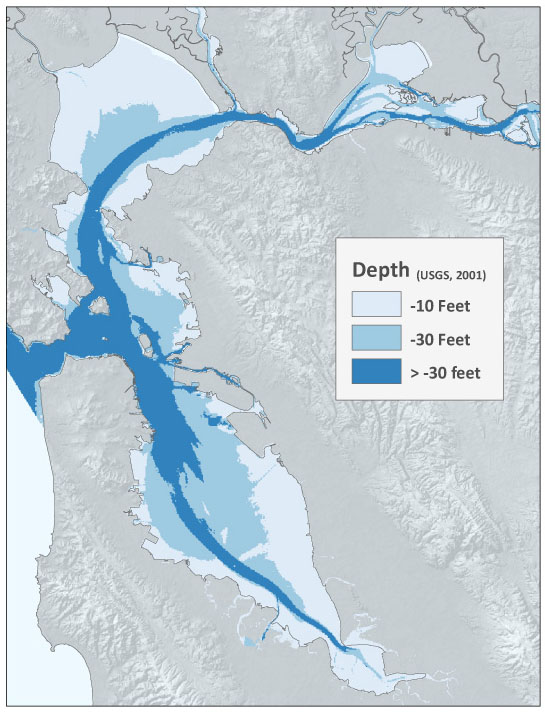

But those places, though easy to see, are dwarfed by 250,000 acres of what scientists call the Bay’s “subtidal habitat”–endless mudflats, occasional rocky areas, beds of bright green eelgrass, undulating ten-foot-tall sand waves, all below the lowest low tide.

“This is the predominant habitat in the Bay, but it’s always submerged, so it’s kind of out of sight out of mind,” says Marilyn Latta, who is managing an ambitious project for the state Coastal Conservancy to formulate 50-year goals for researching, protecting, and restoring San Francisco Bay’s underwater habitats.

The draft “Subtidal Habitat Goals” report was released on Wednesday, June 16, for a 45-day public comment period (through the end of July). A final report is expected in November, though any action on the ground, or water, will await both funding and coordination among the many nonprofits, agencies, and academic institutions at work in the Bay.

The draft report makes for wonky reading, but it’s peppered with surprises: Who knew that every year two million tons of sand are mined out of the Bay for use in local construction? Or that ancient oyster shell deposits are mined for chicken feed and dietary supplements? Or, perhaps more mind-boggling, that researchers with the San Francisco Estuary Institute painstakingly mapped 33,000 abandoned pilings in the Bay? The researchers estimate there are twice as many as that, and the posts present an ecological dilemma: they’re covered in toxic creosote (often derived from coal), so it seems like a good idea to get rid of them, but they also provide some of the few remaining places for certain kinds of animals to live (think of mussels that need hard surfaces to latch onto).

That’s the kind of data gathering, and tough decision-making, that the authors of the report hope to inspire, and coordinate, over the coming five decades. It won’t be easy, but the Bay has come a long way. Fifty years ago, the official vision for San Francisco Bay was as a glorified shipping lane and sewer channel, with thousands more acres filled and covered with housing. The nonprofit Save the Bay was born out of the successful fight to chart a different course. In 1999, government officials and Bay advocates developed a single, overarching plan for restoring tidal marshes that, a decade later, has helped attract researchers and funding that now fuel the largest restoration projects west of the Mississippi.

The new subtidal plan includes many open-ended research questions, but also specific goals, such as vastly improving local capacity to respond to oil spills, completely eliminating several invasive plants and animals, doubling the acreage of eelgrass beds (important nurseries and feeding grounds for fish and other marine life), and getting a much better handle on how sea-level rise due to climate change will affect seal rookeries, waterbird habitat, and other important elements of the Bay ecosystem.

Only time will tell if the Subtidal Goals project will be as successful as past efforts to protect and restore the Bay and its tidal wetlands. But Mary Selkirk, of Sacramento State’s Center for Collaborative Policy, who has worked on the plan, hopes it will be. “This is completing the picture of what we need to understand about what a healthy bay is,” she says, “including all the organisms we can’t see.”

.jpg)