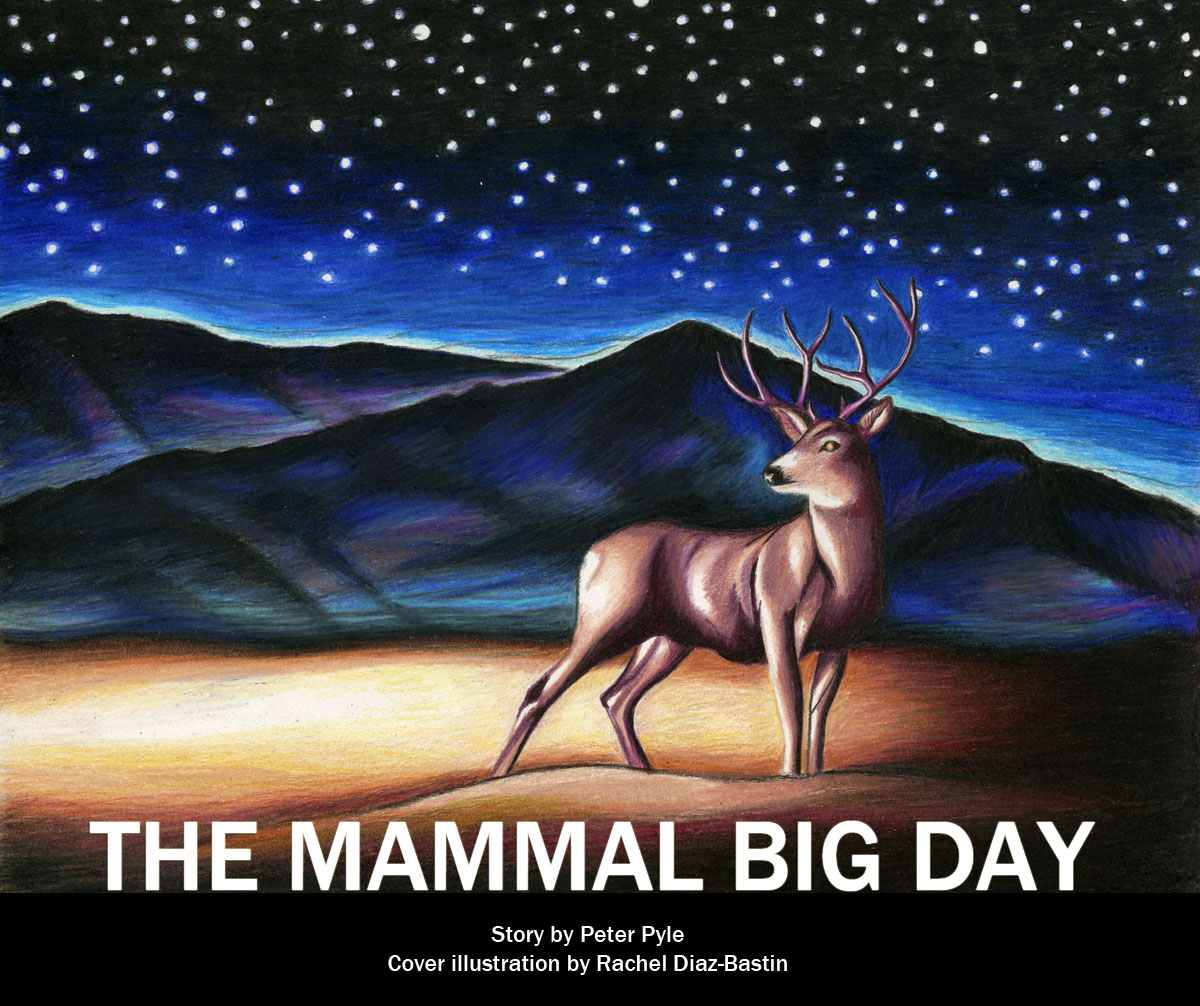

The idea of recording as many mammals as you can see in 24 hours hasn’t caught on the way the birding big day has. But when a team of longtime biologists set out into the field, their efforts netted them some important new information about Northern California’s wild mammals — and a new North American record.

1. After Midnight

We started the big day exactly at midnight at Chimney Rock near Point Reyes. The coastal marine layer descended as mist upon us, but the air was still and cool. As Saturday turned to Sunday we pointed our flashlights into the eerie night, catching the eye shine of three or four mule deer, for native mammal species number one. Six minutes later a northern elephant seal trumpeted from the beach below, and then a striped skunk crossed in front of our car as we drove away from the deserted parking lot. At 1:33 a.m. a bobcat slunk into the night at the base of the Estero Trailhead. We had earlier found a dead Pacific jumping mouse – a species I’d barely even heard of before — on the road near the Bull Point Trailhead (we gathered it up to send to the California Academy of Sciences), and then, as we debated whether or not to count roadkill, a live jumping mouse went ping-ponging across the Abbott’s Lagoon parking lot. Fifteen minutes later, at 2:10 a.m., we heard northern river otters whistling from the lagoon.

By car and on foot we kept moving around the park, looking and listening. Drakes Beach, Marshall Beach Road, the park headquarters, Point Reyes and south on Highway One. The horizon lightened over Bolinas Lagoon as dawn broke. Checking our list, we had recorded 20 native mammals: mule deer (12:01), northern elephant seal (12:06), striped skunk (12:12), northern raccoon (12:33), elk (12:50), brush rabbit (1:09), deer mouse (1:29), bobcat (1:33), Pacific jumping mouse (1:55), northern river otter (2:10), common gray fox (3:11), Brazilian free-tailed bat (3:35), black-tailed jackrabbit (3:41), pallid bat (4:10), California myotis (4:15), big brown bat (4:18), dusky-footed woodrat (4:48), Townsend’s Big-eared Bat (5:25), harbor seal (6:05), and California vole (6:11).

Before the sun had risen we’d already recorded more mammals in a 24-hour period than anyone, ever, in North America.

Now only one question remained: how much higher could we go on our inaugural mammal big day?

2. The Listers

Birders, and I am one, love their competitive listing. We have life lists, state lists, big-year lists, county lists, yard lists, tree lists, sitting-on-phone-wire lists. “Big days” are a special favorite: how many bird species can you see in 24 hours? Driving like crazy or carbon free? How many do you see pooping in a day; how many do you see copulating? My favorite is the “big-foot hour,” which my Bolinas birding friend Keith Hansen came up with: how many birds can you see in one hour traveling only by foot. Another Bolinas birding colleague, Steve Howell, and I, listed 83 species during a big-foot hour, twice (!), once in Bolinas and once on the Farallon Islands. This may be the birding big-foot-hour record, as far as we know. And some of the largest “yard lists” in North America occur in the Bay Area: 278 species of birds from the house over Bolinas Lagoon that Keith and I shared for a decade in the 1980 and ‘90s, 224 from a single room at Keith’s wildlife gallery, 224, as well, from my yard in between, and 366 species of birds from the small yard that we outlined around the old Victorian house on the Farallon Islands.

But how often do you hear about competitive mammal listing? Mammals are generally a lot drabber, more nocturnal, and harder to see than birds, the primary reasons “mammalling” has never taken off like birding has. In addition, people are often drawn to animals that reflect their own personalities, and perhaps mammal enthusiasts are more sedentary and nocturnal than birders are, preferring to hole-up nearsightedly in their dens than to flit around, hyperactively, keeping track of everything in all directions, as birds and birders do. That’s why, no doubt, it took a birder – actually, several birders – to think about moving on to other animals.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

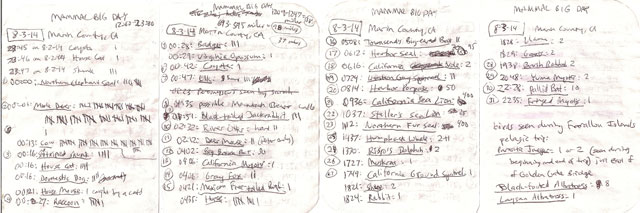

The Mammal Big Day Table of Species

List of Native, Introduced, and Domesticated mammals observed during the Mammal Big Days in 2013 and 2014. Sequence, common names, and taxonomy follows the Smithsonian’s 3rd Edition of Mammal Species of the World (Wilson and Reeder). Numbers in parentheses are estimated observed totals of the species for the day.

| COMMON NAME | SCIENTIFIC NAME | 2013 | 2014 |

| Native | |||

| Californian Myotis | Myotis californicus | 04:15 (5) | 04:06 (20) |

| Fringed Myotis | Myotis thysanodes | 22:35 (1) | |

| Yuma Myotis | Myotis yumanensis | 19:55 (1) | 20:48 (2) |

| Big Brown Bat | Eptesicus fuscus | 04:18 (10) | 04:02 (30) |

| Townsend’s Big-eared bat | Corynorhinus townsendii | 05:25 (100) | 05:08 (2) |

| Pallid Bat | Antrozous pallidus | 04:10 (3) | 22:28 (10) |

| Brazilian Free-tailed Bat | Tadarida brasiliensis | 03:35 (6) | 04:21 (1) |

| Brush Rabbit | Sylvilagus bachmani | 01:09 (2) | 19:38 (2) |

| Black-tailed Jackrabbit | Lepus californicus | 03:41 (3) | 01:51 (2) |

| Mountain Beaver | Aplodontia rufa | 01:35 (2) | |

| California Ground Squirrel | Otospermophilus beecheyi | 18:18 (2) | 17:49 (1) |

| Western Gray Squirrel | Sciurus griseus | 06:55 (2) | 07:24 (2) |

| Deer Mouse | Peromyscus maniculatus | 01:29 (3) | 02:12 (2) |

| Dusky-footed Woodrat | Neotoma fuscipes | 04:48 (2) | |

| California Vole | Microtus californicus | 06:11 (1) | 06:16 (2) |

| Common Muskrat | Ondatra zibethicus | 17:27 (1) | |

| Pacific Jumping Mouse | Zapus trinotatus | 01:55 (1) | |

| Coyote | Canis latrans | 00:42 (1) | |

| Common Gray Fox | Urocyon cinereoargenteus | 03:11 (1) | 04:06 (3) |

| Northern Fur Seal | Callorhinus ursinus | 11:25 (100) | 11:12 (400) |

| California Sea Lion | Zalophus californianus | 10:30 (100) | 09:36 (400) |

| Steller Sea Lion | Eumetopias jubatus | 10:30 (5) | 10:37 (25) |

| Harbor Seal | Phoca vitulina | 06:05 (100) | 06:12 (95) |

| Northern Elephant Seal | Mirounga angustirostris | 00:06 (4) | 00:00 (10) |

| Northern Raccoon | Procyon lotor | 00:33 (8) | 00:27 (6) |

| American Badger | Taxidea taxus | 00:28 (4) | |

| Northern River Otter | Lontra canadensis | 02:10 (1) | 02:32 (2) |

| Striped Skunk | Mephitis mephitis | 00:12 (2) | 00:13 (4) |

| Bobcat | Lynx rufus | 01:33 (1) | |

| Humpback Whale | Megaptera novaeangliae | 12:31 (2) | 14:37 (3) |

| Common Bottlenose Dolphin | Tursiops truncatus | 15:33 (2) | |

| Risso’s Dolphin | Grampus griseus | 13:30 (1) | |

| Harbor Porpoise | Phocoena phocoena | 08:20 (5) | 08:14 (50) |

| Dall’s Porpoise | Phocoenoides dalli | 12:02 (10) | |

| Elk | Cervus elaphus | 00:50 (1) | 00:47 (3) |

| Mule Deer | Odocoileus hemionus | 00:01 (50) | 00:01 (71) |

| Introduced | |||

| Virginia Opossum | Didelphis virginiana | 00:58 (2) | 00:29 (1) |

| House Mouse | Mus musculus | 00:21 (1) | |

| Fallow Deer | Dama dama | 04:41 (5) | |

| Domesticated | |||

| Domestic Man | Homo sapiens | 05:25 (450) | 06:00 (600) |

| European Hare | Lepus europaeus | 18:24 (2) | |

| Domestic Dog | Canis familiaris | 03:51 (3) | 00:16 (8) |

| Domestic Cat | Felis catus | 05:57 (2) | 00:16 (3) |

| Domestic Horse | Equus caballus | 05:05 (10) | 04:35 (8) |

| Livestock Cattle | Bos taurus | 00:30 (30) | 00:13 (100) |

| Domestic Llama | Lama guanicoe | 18:28 (1) | |

| Domestic Goat | Capra hircus | 18:32 (5) | 18:29 (2) |

| Domestic Mouflon Sheep | Ovis aries | 18:21 (2) |

On a spring day a couple of years ago, Floyd Hayes, a birder, and his wife happened to see nine mammals during an early morning drive to the Sacramento Airport and back to their home in Napa County. In Bodega Bay later that afternoon they spotted three marine mammals, and they finished with a bat in the evening, for a total of 13 native species in one day. Floyd posted something about his mammal big day to the North Bay Birds listserv, went looking online to see if anyone had done mammal big days before, and if so, what they’d found. The top list he could find for North America was for 17 native species, seen by the late beloved birder Rich Stallcup during a birding big day in Marin County. (A much higher total of 42 species of mammals was reported in one day from Africa.)

As a biologist on the Farallon Islands, I would sometimes try casually to see as many mammal species as I could on the days in which I traveled from the island, via a Farallon Patrol boat, back to the mainland and home to Bolinas. An average day would result in five pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) and four cetaceans (typically two or three whales and one or two dolphins or porpoises) before the boat docked in San Francisco Bay. Then, during my drive home, I’d look for deer, squirrels, chipmunks, and rabbits during the afternoon and foxes, raccoons, skunks, and bats during the evening. My record was also 17 native mammal species in one day.

When I saw Floyd’s NBB post I replied with my list, and he immediately threw down the gauntlet: surely with an organized effort 17 species of mammals in one day could be topped! We began to strategize a Mammal Big Day.

People are often drawn to animals that reflect their own personalities, and perhaps mammal enthusiasts are more sedentary and nocturnal than birders are, preferring to hole-up nearsightedly in their dens than to flit around, hyperactively, keeping track of everything in all directions, as birds and birders do.

The first thing to do was to pick our route. We decided Point Reyes National Seashore held the highest potential in the immediate area, accommodating elk and American badger, both species impossible or difficult to find elsewhere in the Bay Area. I had friends and colleagues who worked for the National Parks who knew the seashore’s animals inside and out. Sarah Allen, a park service birder, ecologist, and mammalogist, had kept track of all of the seashore’s mammals. USGS ecologist and herpetologist Pat Kleeman and USGS emeritus research biologist and birder Gary Fellers have spent a lot of time prowling around the park at night, studying red-legged frogs and bats, and monitoring mountain lions, mountain beavers, and other mammals via motion-sensor trip cameras. Gary and I have one more thing in common, direct relatives who tramped around the Pacific in the early 1900s discovering and collecting animals, primarily off California and Hawaii. At one point Gary’s uncle and my grandfather were roommates on one of the Whitney South Sea Expeditions sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History. For us, a Mammal Big Day was in our blood!

We decided that a Mammal Big Day must also include a trip to the Farallon Islands to record pinnipeds and cetaceans, most of which cannot be found or seen from shore. We figured late summer would be the best time of year, offering an adequate amount of daylight to see diurnal mammals before and after a boat trip, plenty of darkness on either side, and a lot of newly weaned young mammals out and about. Debi Shearwater of Shearwater Journeys happened to offer a birding and nature trip to the Farallones on August 4, 2013, so we planned our day around this trip, which left Sausalito at 7:30 a.m. and returned to the dock around 4 p.m. On that day Pat was doing fieldwork in Yosemite National Park and Gary was in New Zealand, but Sarah jumped at the chance and we had our team of three for our first Mammal Big Day. If we were to beat the record, we decided to suck in our guts and go midnight-to-midnight, if possible. We set about planning the exact minute-by-minute itinerary, and checked online and with other colleagues for recent sightings of rarer mammals.

We also had to establish Mammal Big Day rules. It turns out there are more things to consider than there are for birding big days. Could we use live traps? Could we put out seed or other food? Could we count mammals heard but not seen and, if so, does rustling count? What if we smell a skunk but don’t see or hear it? What about road kill? Scat? Sign? What about non-native and domestic mammals? And, finally, do humans count?

We decided to keep to the spirit of birding big days as much as possible, so we could not trap, but mammals heard but not seen would count. We could visit bird-feeding stations but we would not throw out seed or other food the day before, to prevent introducing non-native grasses or otherwise affecting the environment negatively. (Except for shining lights into fields along the road we kept our wildlife-disturbance levels to a bare minimum.) As for road kill, scent, scat, and sign, we decided to cross those bridges if needed. (Thus far, road kill, scent, and scat would not have added to our totals, and we decided not to count sign because we could not determine whether or not it had been affected that day.) We decided to make three lists, one each for native, introduced, and domesticated mammals, of which the first was by far the priority target list.

As for humans? Well, we debated all four possibilities: not counting them at all, or counting them on each of our native, introduced, or domesticated lists. All four outcomes could be defended, but we decided that the domesticated list was the most appropriate place for Homo sapiens. If any mammal can be considered “domesticated,” it would be us, and we preferred to be on the outside looking in on a non-domesticated arena.

3. Marine Mammals

On our way that first day from Bolinas to the boat in Sausalito, we picked up a western gray squirrel (6:55) giving us 21 native species. For the next eight hours we could relax somewhat on the Farallon tour, a trip I had performed nearly 100 times. We could not forge after mammals; rather, they had to come to us. Harbor porpoises (8:20) broke the water’s surface under the Golden Gate Bridge, for species number 22, but the two-hour passage to the island was foggy, gray, and uneventful, and we used this time to doze off. At the island we easily tallied California and Steller’s sea lions (10:30) on the surrounding rocks, as well as northern fur seals (11:25), which have recently re-colonized the islands as a breeding species. (In 1996 I happened to encounter the first pup to have been born there in more than 100 years.) We then ventured south of the island in search of cetaceans and saw Dall’s porpoise (12:02) and humpback whale (12:31). A small group of common bottle-nosed dolphin (3:33) below Lands End gave us 28 species for the day.

After the boat trip we were able to find only two more native species of land mammals, California ground-squirrel in Nicasio (6:18) and Yuma myotis at Five Brooks (7:55), for a total of 30, before capping the effort back in Point Reyes Station at 10:20 p.m., too bleary-eyed to go on looking and listening for a coyote, one of a few species we were surprised to miss. Nevertheless, we were quite happy with our total – we had topped the previous record in North America by 13 species!

And yet …

Based on what we’d learned from the day, plus a bit more scouting and research, we knew we could do better.

4. Finding the Mountain Beaver

We got our opportunity almost exactly a year later, on August 3, 2014. Sarah and Gary could not go on the boat trip in 2014, but Sarah joined Floyd, Pat, and I for the midnight-to-dawn portion of the effort while Gary joined us for late afternoon through the end. Based on our perceived success in 2013, we followed a similar early-morning route from Chimney Rock to Sausalito. Although we only tallied 19 species by boat-departure time, two less than in 2013, we had deferred looking and listening for a couple of bat species from the morning to the evening, so we were more or less on target. (We missed bobcat, Pacific jumping mouse, and dusky-footed woodrat, but we made up for it with a coyote and three American badgers, which we missed in 2013.) Undoubtedly the highlight of the 2014 morning, though, was our possibly being the first post-colonization humans ever to identify the vocalizations of the Point Reyes mountain beaver.

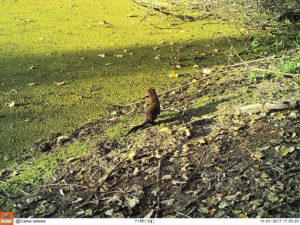

I have forever wanted to make contact with the mysterious Aplodontia rufa phaea, as science knows the local mountain beaver. These primitive, nocturnal, nearly tail-less rodents live in honeycombed tunnels under inaccessibly dense vegetation on steep slopes near streams, and are essentially impossible to see without considerable patience, effort, and a good pair of night-vision goggles. The Point Reyes population is nearly endemic to the national seashore area and it was quite rare, even before the 1995 Mount Vision fire wiped out about 40 percent of the population. We did not even look for them on our Mammal Big Day in 2013, so hopeless it seemed to see one. In 2014, however, I wanted to at least try to see a burrow, and Gary let us know of a semi-accessible colony area in which we could scrounge around. While we unsuccessfully peered through the impenetrable thickets for a burrow, a distinctive nasal sound, jee-jurr, emanated from the dense brush on the slope above us. It reminded me of one of the calls of the endangered black rail. But it was not a bird — rather, it had the distinct quality of a rodent call. At the time we figured it had to be either a mountain beaver or a dusky-footed woodrat, and when Gary later confirmed that woodrats were not found at that locality, we chalked up Aplodontia to our list. A few nights later, Pat set out an automated acoustic device and obtained a recording of the call. If it is that of a mountain beaver, as we suspect, not only is it new information on this species’ calls, but it could be used to survey and monitor this rare and potentially threatened subspecies in the seashore. The possible mountain beaver encounter exhilarated us in the same manner that an unusual or unexpected vagrant bird will put charge into a birding big day.

These primitive, nocturnal, nearly tail-less rodents live in honeycombed tunnels under inaccessibly dense vegetation on steep slopes near streams, and are essentially impossible to see without considerable patience, effort, and a good pair of night-vision goggles.

Following the same (unavoidable) route and schedule, we recorded six additional marine mammal species on the 2014 Farallones trip, for 25. Compared to the 2013 trip, Dall’s porpoise and bottle-nosed dolphin eluded us, while we picked up a Risso’s dolphin. As the boat pulled back into the harbor in Sausalito, we felt equivocal about meeting our record from the previous year. Although we had two “stake-out” bat species to get, this still left us one behind our 2013 pace. But ambivalence turned to hope again when we spotted a common muskrat at Las Gallinas Wildlife Ponds, and quickly got California ground-squirrel at the nearby Rush Creek Open Space Preserve. Back in West Marin, we easily found our two deferred bat species, getting us to 30 and equaling our 2013 total. At 10:35 p.m., Gary spotted a fringed myotis among other roosting bats.

Once again, the North American record had been raised. For now – until our next attempt, at least – that’s where the record will stand.

In achieving our 2014 total of 31, we missed five native species that we recorded in 2013, while recording six species that we had missed. We had bad luck in both years with cetaceans, recording four and three species, respectively. On a typical early August day we could have recorded up to seven or eight cetacean species: gray whales are nearly annual in summer near the Farallones (with the exceptions of 2013 and 2014), and blue whale, killer whale, Pacific white-sided dolphin, and northern right-whale dolphin were all encountered there during the previous week. Had we been able to see all land-based species observed in both years, plus four more cetaceans, it would have given us 40, just two short of the African record. And then, of course, there are the species we missed in both years.

5. Always Something To Miss

Every birding big day seems to have one or two species that are, unexpectedly, just plain missed, for no apparent reason, as if the birds move in patterns to avoid being listed. Chalk it up to bad luck, bad karma, a corporate plot, or all three of these things. Whatever the case, we had a couple of mammal species that we missed during both 2013 and 2014 that we did not think would be difficult to find.

Botta’s pocket gopher (a.k.a. “gopher”), for example. Gopher mounds are everywhere, correct? And they are always poking their heads up, right? Well, yes and no. In 2013 we figured we’d get them outside of Sarah’s office window at the Bear Valley headquarters, where there is a settlement of mounds from which they regularly poke their heads up … at least some of the time. But by the time we got there after the boat trip it was foggy and cooling down, and there was not even a bit of moving dirt among the mounds; they had all gone to bed! So, in 2014, we looked for them right after the boat trip in East Marin, where it was warmer and sunnier. We checked many fresh mounds up the Highway 101 corridor, including numerous digs in Novato schoolyards and lawns, but again, no movement. The holes at the tops of the mounds were all sealed up. We realized that none of us had any idea about gopher activity patterns! In addition to preferring warmer weather, they are probably more visible in spring than in mid-to-late summer, when lawns and fields have dried up.

The other big miss during both big days was Sonoma chipmunk, especially since, in both years, three or four were visiting birdseed I put out near our Bolinas yard. They are constantly tseeking along our block, and so we planned a post-dawn stop there to get these, along with California voles, which can be found on Kent Island in Bolinas Lagoon. In 2013 we had to leave Bolinas at 6:15 a.m. to get to the Sausalito dock by 7, and they simply did not appear or tseek that foggy morning before we had to leave. We then spent two afternoon hours driving Mount Tamalpais, visiting numerous locations where I know them to be present, but the woods were frustratingly silent. Like the gophers, the chipmunks appear to be early to bed and late to rise.

I paid more attention to our yard chipmunks in 2014. During the week before our Mammal Big Day, I put out seed at night and regularly heard or saw them by 6:30-6:45 the following morning. So I arranged with Debi Shearwater for an extra 45 minutes, giving us until 7 a.m. before we had to depart Bolinas for Sausalito. But, again, for unknown reasons, they were absent and silent until we had to hastily depart to catch the boat! We listened with open windows again later in the afternoon, but we never heard so much as a tseek. They were beginning to seem less cute in our minds.

The morning following the 2014 Big Mammal Day, I got up around 6:45 to be greeted by two chipmunks, tseeking at me because I had not cared to put out seed after stumbling home the night before. Now, I’m not a hunter, preferring we had the right to arm bears instead of what we ended up with today. However, perhaps mentally impaired by just 6 hours of sleep over the previous 48, I temporarily recalled William Leon Dawson’s account of the Bufflehead in his 1923 classic, Birds of California:

If any sight in nature could disarm the powder-lust, it would be that of a half dozen Buffleheads dancing upon the sun-kissed waters of some southern lagoon. Dapper, jaunty, bright-eyed, elegant, and altogether charming are these dainty duck children. Their white breasts gleam in the sun, and they ride so high in the water that they seem more like fluffs of floating cotton than creatures of avoirdupois. If that captivating drake, now, would only let us handle him, we should be perfectly satisfied. We would cuddle him in our arms, and stroke his puffy cheeks of rainbow hue, or give a playful tweak to his saucy little nose. But he does not fully appreciate our benevolent attitude; he does not immediately reciprocate our desire to fondle him — therefore, we will give him the left barrel.

Such letdowns and misses will certainly not stop us from more attempts at Mammal Big Days. Besides having a blast, was there any purpose to our using up carbon (we at least drove a Prius) for what could be construed as a completely goofball sport? Absolutely! Instilling an appreciation for nature is the best way to preserve it, and we have already enthused others with what we have learned, planning for and undertaking these Mammal Big Days. I’ve obtained a bat detector, which I’m now using year-round to learn more about bats in California, sharing their calls with excited kids and adults alike. We have learned a few things about mammal behavior in the area: where badgers can be seen and otters heard, how to identify jumping mice, and the daily snoozing regimes of chipmunks and gophers. And there is still more to learn: where and how might we find a shrew, or a mole, or a shrew-mole; a spotted skunk, a harvest mouse, or the affable but provocative ringtail? Had we not undertaken Mammal Big Days we would not have discovered what is likely the call of the clandestine Aplodontia, to help with their future monitoring and conservation.

And there is still one big quarry out there. After 35 years of living and stalking wildlife in Marin County, I have never encountered a mountain lion, and I have to wonder if I ever will. I’ve had friends who moved into the county and saw one their first week here. Beginner’s luck? Too late for me on that score. But someday I will, and when I do, it will be a “big mammal day” even if I don’t see anything else.

Epilogue

After publicizing our Mammal Big Day in 2014 we got word from Eileen and Brian Keelan that they had also been doing Mammal Big Days in the Santa Cruz Mountains and Pinnacles National Monument, winding up with 27 species during their 2014 attempt on August 23. The Keelans observed 10 land mammals that we missed in 2014, and they have kindly offered to combine forces on a future Mammal Big Day, an offer we are strongly contemplating for 2015!