Technically, we’re cheating. Or we would be, if we were competing in the Dipsea Race, the nation’s oldest cross-country running competition, dating back to 1905. The grueling 7.4-mile trail starts in downtown Mill Valley, climbs the slopes of Mount Tamalpais, and then drops nearly 1,400 feet to Stinson Beach. I’m hiking the famous trail a month before the June race with two National Park Service scientists. We skip the first two miles of trail, which crisscrosses paved roads, in favor of setting out on dirt near the Muir Woods National Monument visitor center. On my own, I’d focus on the old-growth redwoods and ocean views as I tackled the steep terrain. But there’s far more here than legendary trees and vistas, my guides tell me. The Dipsea passes through a shifting suite of habitats that supports remarkable biodiversity. You just have to look for it.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Mount Tamalpais: A Mountain of Stories

A Mountain of Stories was produced by Bay Nature magazine with the generous support of the Tamalpais Lands Collaborative for publication in the October-December 2017 issue of the magazine. Read more stories from the mountain:

- Meet Mount Tamalpais, by John Hart

- Nature and Culture Mix in a Theatre Among the Oaks, by Claire Peaslee

- The Nature of the Dipsea Race, by Alisa Opar

- Alice Eastwood and the Plants of Tamalpais, by John Hart

- On the Hunt for Mount Tam’s Two Known Badgers, by Mary Ellen Hannibal

- Snorkel Surveys Reveal the World of Mount Tam’s Creeks, by Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

We step onto the trail and enter the shaded redwood understory along Redwood Creek, a 6.5-mile waterway that begins in the peaks of Mount Tam and spills into the Pacific Ocean at Muir Beach. On race day, most of the 1,500 runners who pound over the creek on wooden planks won’t know endangered juvenile coho salmon are swimming in the inches-deep water below. Today the makeshift bridge is missing. The National Park Service removes it, every winter through late spring, to ensure it won’t impede the two-foot-long adult coho and steelhead trout that journey from the ocean to spawn in these shallow waters. Coho need all the help they can get. Habitat loss, pollution, and poor ocean conditions mean fewer than a dozen adults return to Redwood Creek each year, despite restoration efforts. To boost their numbers, Michael Reichmuth, a fisheries biologist for Point Reyes National Seashore, and his team have partnered with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, along with other groups, to begin collecting juveniles from the creek, rearing them to adulthood in captivity, and then re-releasing them here to breed. Reichmuth points out a couple youngsters—tiny silver flashes in the shallow water—and we hike on.

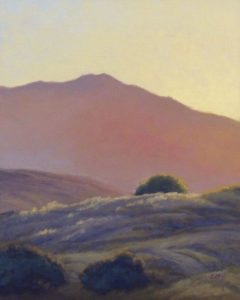

Up, up, up we climb, moving out of Muir Woods and into Mount Tamalpais State Park—and direct sunlight. Alison Forrestel stops us. I gratefully catch my breath as Forrestel, a vegetation ecologist with the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, goes into detail about the landscape. This seven-mile trail winds through many of the ecosystem types found within the 53,000-acre One Tam area. We’ll see oak woodlands in a couple of hours, when we reach the coast. Behind us are towering redwoods, and green-gray shrublands cover a distant hillside. Immediately in front of us is a sweeping grassy hillside, called Hogback. In the One Tam area, grasslands comprise about 10 percent of the open spaces, providing herbaceous expanses for American badgers and dozens of species of songbirds to forage and raise their young.

Forrestel explains that keeping meadows like this healthy requires intense vigilance and person-power. She points to a stand of Douglas-fir at the edge of the grasses; fires formerly prevented the trees from encroaching on and taking over the grasslands, but now land managers must remove them. Invasive plants are an even bigger challenge. French broom, for instance, the fast-growing evergreen shrub likely introduced to the Bay Area as an ornamental in the mid-1800s, today swiftly chokes out natives—from iconic purple needlegrass to rare star tulips. There’s no French broom in sight on Hogback, thanks to the staff and volunteers who clear the intruder by hand and keep close watch for seedlings. They concentrate on clearing invasive nonnative plants from trail edges, where humans unwittingly pick up, transport, and deposit seeds. (The quirky rules of the Dipsea race allow runners to take shortcuts, but Forrestel suggests sticking to the trail—if not out of concern for the ecosystem then for personal well-being, as poison-oak is rampant along the course.)

We soon get some respite from the strong sun as we cross back into Muir Woods and enter a patch so noticeably sodden that runners nicknamed it “the Rain Forest.” Thick summer fog accumulates here, causing moisture to drip like rain off the redwoods, tanoaks, and Douglas-firs. These old-growth woods receive about twice the annual precipitation of Stinson Beach, only a few miles away. Redwoods and other fog-dwelling plants have evolved to take advantage of the moisture by absorbing it through their leaves, not just their roots like most flora. So far, the coastal redwoods have survived the extended drought, but how the trees will fare in the future is uncertain (in part because fog is tricky for climate models to forecast). If rising global temperatures lead to more frequent droughts or decreased fog, some trees and organisms living beneath their soaring canopies could suffer—including coho salmon, which live primarily in the cool, shaded streams of redwood forests, Reichmuth points out. Another concern, Forrestel says, nodding to two dead trees in front of us, is Sudden Oak Death. The pathogen, a mold that scientists believe came over from Asia in the nursery trade (though that remains unconfirmed), is killing tanoaks in Muir Woods and beyond: The disease has infiltrated 90 percent of One Tam’s oak woodlands and killed tens of thousands of its trees. Besides tree loss, it’s worrisome because dusky-footed woodrats, the preferred prey of the endangered northern spotted owl, dine on acorns.

I’m despondent to learn there’s no way to stop the pathogen, but my mind turns elsewhere as we approach the infamous Cardiac Hill. For years a “No U-Turn” sign at the base goaded runners, signaling they were about to trudge up the Dipsea’s steepest section. A sign marks the trail’s highest point, at 1,360 feet, and relates the history of the race, accompanied by a black-and-white photo of dozens of men dressed in suits, ties, and flat caps jauntily cresting Cardiac.

We take in the Pacific stretching to the horizon, sip from the only water fountain on the trail, and then head (mostly) downhill for the final three miles. For half that distance we cut across hillsides, passing through grasslands and shrubland dominated by coyote bush; its fluffy white seeds look a lot like that canid’s tail. We startle a deer and her white-speckled fawn, and a lone turkey vulture wobbles overhead. Biological surveys of One Tam’s coastal shrublands reveal that they’re healthy, supporting a rich mix of songbirds—something that’s obvious even during the non-birdy midday hours. Bushtits and orange-crowned warblers zip around low in the shrubs, and the insistent, bright “chip” of the California towhee pierces the air, though the large brown sparrow remains invisible.

I cringe when I see the sign for our turnoff; if Cardiac Hill busted my lungs, Steep Ravine seems certain to strain my knees. We drop sharply through redwoods, and a few minutes later, the dirt trail becomes stairs, slick with moisture. I lose count somewhere north of 100, distracted by the recollection that top runners were rumored to take the steps four at a time. Finally, we reach Weill Creek at the bottom of the ravine. Reichmuth spots a rainbow trout. It’s the same species as the steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Redwood Creek, he explains as we move on, but rainbows live only in freshwater, while steelhead take their chances in the ocean.

Suddenly, we emerge from the woods onto a hill with a spectacular vista of Stinson Beach. We’ll soon make our way down to the sand to rest our tired legs and eat lunch. But first Reichmuth points out Bolinas Lagoon, a tidal estuary north of Stinson where leopard sharks prowl and harbor seals haul out. The marshy trough, he says, was formed by the San Andreas Fault, which runs directly beneath it.

On a day filled with discovery, forced to slow down and observe my surroundings instead of breezing through, I’m struck by this revelation. The San Andreas Fault, born millions of years ago when the Pacific and North American plates first collided, shaped this landscape. Those ancient geological forces wrought the mountains, streams, and rugged coastlines we’ve traversed on the Dipsea, paving the way for abundant biodiversity within a few short miles.