Seven and a half-mile loop trail on paved and gravel paths from San Francisquito Creek to Charleston Slough.

It’s nearly dusk on the salt marsh, and the setting sun bathes the scene in a fading golden glow. Suddenly the calm is broken by a raucous barrage of sound, an uncoordinated clattering chorus that echoes in all directions. This clattering, or “clapping,” as the signature vocalization is known, is heard long before the shy birds that produce it are ever seen, giving the species an aura of mystery—and its name: clapper rail. At dusk and dawn these contact calls bounce over the marsh from nest to nest, like iterations of an ancient watchman’s “All’s well!”

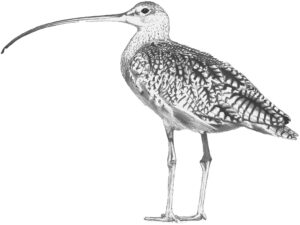

The California clapper rail (Rallus longirostris obsoletus), the Central Coast subspecies, now resides only in remnant tidal marshes around San Francisco Bay. First declared endangered in 1970, the species is now making a slow comeback from its low point of 300 individuals.

How does one go about glimpsing this elusive rare bird, so emblematic of the struggles to save San Francisco Bay? A visit to the Palo Alto Baylands segment of the Bay Trail at the right tide provides the best opportunity. The most reliable time to spot the clappers (and their even more elusive relatives the sora, Virginia rail, and black rail) is at the peak of the highest winter tides, typically near full moon or new moon, when rising waters force them out of hiding. The other time to look for clappers is at any low tide, as they feed in the marsh channels.

Like the clapper rail, these tidal marshes have had a close brush with extinction. Along the edges of the marshes, we humans encroached on a wetland that once stretched far beyond the freeway: golf course, airport, roads, businesses, and landfill all make this, at first glance, an unlikely place to find a reclusive endangered bird. Here, as elsewhere, the higher marsh—easier to build on—went first. The remaining marshes had a close call in the 1950s. As Palo Alto resident Harriet Mundy later explained, it was only because she went to the city council to complain about a broken sidewalk that she discovered a big Baylands development plan ready to roll, complete with condominiums, a hotel, and a marina—but no marsh. Mundy and other citizens harassed and educated the council for a decade, until the city dedicated the Baylands Nature Preserve in 1969.

Thanks to the preservation and subsequent restoration of the marshes, the Bay Trail at the Palo Alto Baylands has become a prime location for seeing all sorts of marsh and water birds. Trail access starts at the end of Geng Road and then follows San Francisquito Creek, a steelhead stream now the focus of cooperative restoration efforts by several groups. (Note: Access from Geng Road is closed through November 2002 due to construction; until then, visitors should proceed directly to the Baylands Nature Center.)

As the levee trail leaves the creek, true saltmarsh vegetation takes over. Resident shorebirds—stilts and avocets—demonstrate their feeding styles in the shallows of the lagoon and tidepools. The stilts balance on the long legs that give them their name, and reach down to pluck small invertebrates from the water. The closely related avocets swing their recurved (upturned) bills back and forth along the surface of the mud. In fall and winter, look too for ducks and shorebirds of all descriptions, attracted to the food-rich edge of the Bay on their migration along the Pacific Flyway. Soon the Lucy Evans Baylands Nature Interpretive Center—named for another Baylands heroine—comes into view, balanced on stilt-like legs over the marsh tides and attached to one end of the boardwalk.

Inside the center you’ll find plenty of information about birds and other denizens of the marsh. Outside, you can try out the new spotting scopes. One scope, like the Bay Trail itself, is friendly to wheelchair riders.

Descending to the marsh on the boardwalk, look for tracks in the mud and the stories they tell; for example, it is only because of its oversized toes that the rail can move about on this spongy surface. At winter high tides song sparrows, marsh wrens, and common yellow-throats perch on tall plants. Look too for salt crystals exuded onto the leaves of cordgrass and salt grass, and for the lingering autumn red of the dominant marsh plant—pickleweed—a hiding place for the marsh’s most secretive animals. If you visit in fall or winter, pickle-weed’s peculiar twining parasite, marsh dodder, will have changed color too, its orange summer tendrils turning into a brown mat. Like other marsh plants, its winter destiny is to become detritus, the broken-down bits of biomass floating on the surface waters or sprawled over the mud. This detritus is the crucial base of the Bay’s food chain.

“Rail Alley” is the deeply cut channel that runs under the boardwalk. Here rail watchers and photographers tarry quietly, waiting for their visual quarry, which eventually appears nonchalantly probing and picking along the channel. If you sight a clapper at high tide, wait until the water begins to recede. That’s when the clapper has its feast, wandering about in the open and picking stranded spiders, insects, and even rodents off their vulnerable plant perches above the flood.

- The endangered California clapper rail likes to hide in tall marsh grasses. Photo by Joe DiDonato.

Why is this spot such good “rail estate”? Note how plants overhang the deep channel here, so even a chicken-sized bird like the clapper rail is hard to see from above. Tiny tributaries, even more private, offer quick exits off the main channel. Notice how high these banks are, compared to the rest of the marsh. When banks overflow, the tide drops its largest soil particles first — an advantage to the clapper, who needs a high, dry nesting spot near the best food sources and escape routes. Happily, the tall yellow-flowered gumplant chooses the high marsh too and affords perfect cover for secret nest sites. It’s no wonder that clappers nest no farther from a marsh channel than the spread of a human’s arms.

Though the clapper rail gets most of the press, its small and even more secretive relative, the black rail, is virtually impossible to see anywhere else in its range. Perhaps that is why winter high tides at the Baylands bring another phenomenon: flocks of black rail seekers, as many as 125 at once, from across the nation. The high corner of the marsh by the parking lot is probably the best place anywhere to catch a glimpse of this bird of a lifetime, but only if you are very patient.

Another avian treat awaits those who continue along the trail between the harbor and the Byxbee Park Hills to Adobe Creek. From July through December hundreds of huge white pelicans take advantage of Adobe Creek’s protected habitat. Watch for their cooperative fishing behavior: Several birds swim abreast, herding fish with their feet, then dip their voluminous bills into the “fish pond” they have created. To the left of the trail, Charleston Slough is home to a small colony of black skimmers, another species otherwise rarely seen in the Bay Area. These sturdy tern relatives fish on the fly, stretching their overgrown lower bills into the water as they skim over it.

The skimmers are a fitting exclamation point to a day on the Palo Alto Bay-lands section of the Bay Trail. It has been a day of many birds, many sights, and many sounds, climaxing in the thrill of having briefly entered the world of the California clapper rail, the elusive bird that has become a symbol of both the threats fac-ing the Bay and the hopeful signs pointing toward its long-term revival.

Getting there: From Highway 101 (Bayshore Freeway) take the Embarcadero/East Embarcadero exit in Palo Alto. Turn left at second light, Geng Road, and continue to Baylands Athletic Center parking lot. (While Geng Road access is closed through November 2002, proceed directly to Baylands Nature Center: Stay on Embarcadero past Geng until the “T” intersection, then turn left and follow road to the Center.) There is no direct public transit access.

The Bay Trail Project is a nonprofit administered by the Association of Bay Area Governments that plans, promotes, and advocates for implementation of the 400-mile multiuse Bay Trail. For more information about the trail, or to order the set of six new Bay Trail maps, call (510)464-7900 or visit www.baytrail.org.

.jpg)