In the 150-plus years that we’ve been tracking rainfall in Northern California, it’s never been this dry. It was the driest December in many places, and this week’s drizzle wasn’t enough to keep San Francisco from its driest-ever January. And if there’s an end in sight to the big-picture weather pattern that’s led to the drought, forecasters haven’t spotted it.

“When will it end? That’s the million dollar question,” says Logan Johnson, the meteorological warning coordinator at the National Weather Service Forecast Office in Monterey. “We don’t have any observations to compare with what’s happening now.”

The dry weather has been caused by a high-pressure ridge of air that rises four miles above the Earth’s surface and stretches from Canada to Mexico. The air on top weighs heavily on the air below, causing it to sink under its own weight. As the air gets closer to the Earth, it circles away in a clockwise pattern that pushes colder, northern air to the East and draws warm air from the south up toward the West. As long as the ridge stays put, it blocks the air underneath – our air – from rising, cooling, and condensing to give us rain or snow. The precipitation we need keeps getting shunted away. And while ridging is a common part of California’s weather pattern in both summer and winter, the ridge usually builds for a few weeks then breaks down as storms move through. Not this time.

The “ridiculously resilient ridge,” a term coined by Stanford graduate student Daniel Swain, has hung over us for more than a year. Its persistence has everyone puzzled. Even though a few 10-day forecasts have included the possibility of rain showers, the sunshine keeps showing up.

“In essence, these pressure systems are like eddies in a stream and can stay in place for long periods of time,” Johnson says. Ridge-busting storms usually ride into the West Coast with the polar jet stream – often described as a powerful ribbon of air that travels from west to east at even higher levels in the atmosphere. But the jet stream has shifted upward from its typical winter path, now hugging the northern boundary of the anchored mass of air and taking the storms with it. While that accounts for where the storms went, no one is quite sure why this particular high-pressure ridge won’t budge.

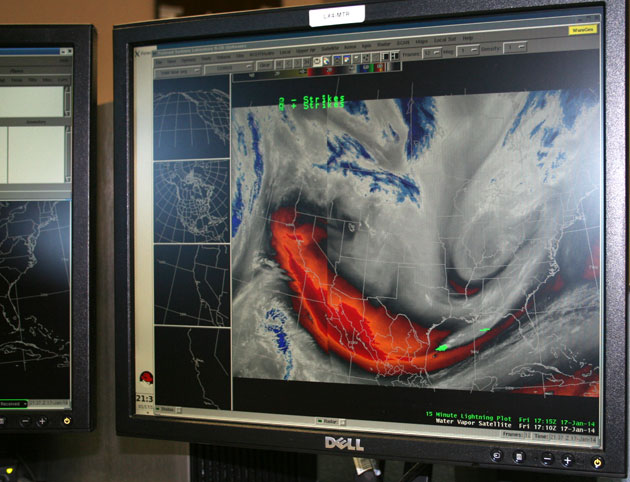

Despite all our technological advances, predicting weather can be a tricky thing. Johnson sits at a bank of computer screens, each monitor flashing with undulating bright lines, multicolored grids, or dream-like swirls of colors that depict recordings of air pressures, temperatures, and water vapor from sites around the Bay Area. Remote radar images come from the station on top of Mount Umunhum, the fourth-highest peak in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Data is collected from a weather balloon launched from the Oakland airport every morning. And twice a day the National Weather Service, based in Silver Springs, Maryland, sends long-range reports that the Monterey meteorologists interpret according to local conditions. But it still comes down to feeding all that information into mathematical equations, or models, that use the history of weather patterns to forecast what will happen in the future. And in forecasting the ridge, there’s that problem again: “No one has ever seen this before,” Johnson says.

It’s hard to pin down the long-range forecasts. Weather modeling follows the chaos theory, developed by Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Edward Lorenz, which says it’s difficult to predict weather beyond two or three weeks with any accuracy. In a 10-day forecast, any incorrect factor in the mathematical models gets amplified during that time frame and all those incorrect assumptions can add up to another day without rain.

While the resilient ridge means Johnson and his colleagues haven’t had to revise the forecast much this winter, the 24/7 forecasting station still has plenty to do. “Even though the weather looks the same, new information is always streaming in,” says Johnson. Two meteorologists work the public affairs section in eight-hour shifts while a hydrometeorological technician handles media inquiries and monitors the reporting instruments to make sure everything is reading correctly. One section is dedicated to aviation and ocean traffic. Every six hours the Monterey forecasters issue reports to the airports in San Francisco, Oakland, Santa Rosa, Salinas, and Monterey. With the high-density population around San Francisco Airport and the potential for international air-traffic jams when the fog rolls in, it’s critical to get the weather details right. The San Francisco Bay is also one of the world’s biggest shipping ports and recreational sailing vessels ply the same waterways as massive ocean tankers. Normally this is the busiest time of year because storms are coming in. But there’s no storm watch now. The forecasters are still tracking fire weather.

For up-to-the-minute weather reports Bay Area residents can follow the National Weather Service on Twitter @NWSBayArea or join the weather-watching community on the US National Weather Service San Francisco Bay Area Facebook page.