The Hayward regional shoreline consists of over a thousand acres of marshes and seasonal wetlands. At low tide sandpipers and black stilts wander about the mud flats searching for food, while cyclists and runners exercise along a 5-mile trail.

It’s hard to imagine that more than a hundred years ago, mounds of salt covered these same Hayward marshes like a fresh blanket of snow. The salt attracted harvesters, going way back to the original inhabitants.

“Ohlone tribes were the first to gather salt crystals from the grass along the marshes, but it wasn’t until the 1850s that settlers began harvesting salt from the ponds,” said Hayward Shoreline Interpretive Center naturalist Patti Workover during a historical tour of the Oliver Salt trail in April.

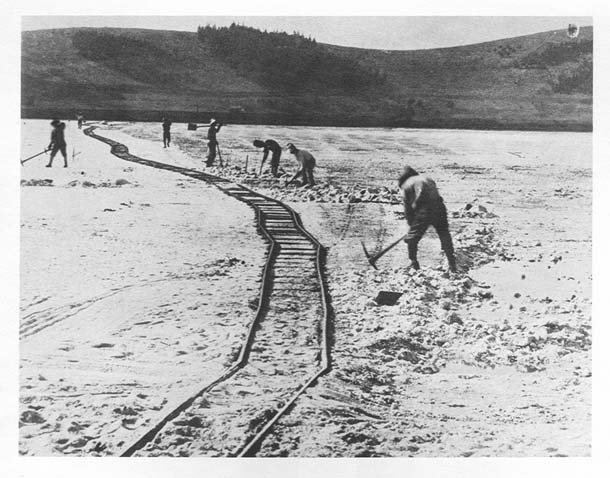

While he didn’t strike gold in 1852, Scandinavian sailor Josh Johnson was the first pioneer to commercially harvest salt from the Bay. To create the ponds, Johnson had Chinese laborers construct channels to drain the marshes and corner off areas where salt could be evaporated. The laborers built levees from wood, stone, and mud to hold off the tides. In fact, one of the wooden levee rollers used by the salt farmers can be spotted on the Oliver Salt trail today.

“Johnson used his boats to bring salty bay water back to the shoreline,” said Workover.

Brine or seawater was fed into large ponds, then moved to shallower ponds and drawn out through natural evaporation allowing the salt to be harvested. Once the pond had evaporated, workers would shovel the crystallized salt by hand and put them into wheelbarrows.

In 1852, Johnson sold his first salt harvest for $35 a ton.Johnson later sold his land to Swedish sailor August Ohleson in 1872. Ohleson would later change his name to Andrew Oliver, whose descendants provided salt to tanneries, food processing, and packaging companies until 1982.During the 1900s, the Oliver family introduced several innovations to the salt harvesting industry, remnants of which still exist on the trail.

One such installation, the 4-inch perforated pipe, worked as a generator said Workover. Similar to native tribes scraping salt off plants, the Oliver’s built a modernized version raising perforated pipes around pine boughs that were placed in the mud.

“Water would pump into the pipes and spray onto the wood. Workers would then scrap the salt off the stumps of the wood — advanced for its time but it was very labor intensive.”

Archimedes screw pumps originally designed and built by Andrew Oliver in the 1870s were the longest surviving wind-powered pumps until electric pumps were built in the 20th century. The 4-bladed wooden windmill was used to funnel water from one pond to another, aiding the evaporation process. On the Oliver Salt trail, you’ll notice two archimedes screw pumps. The remains of the original wooden windmill from the 1870s, and a mechanical windmill.

Another byproduct of the salt trade has been the shoreline’s contribution to aquaculture and the pet fish industry. Unlike many organisms, brine shrimp flourish in salty waters, proving to be a valuable food source to stilts, snowy plovers and other wildlife. Their shell-encased case eggs are sold as fish food and even as a novelty gift: you may know them as Sea Monkeys!

Brine shrimp and algae are also responsible for the ponds’ chameleon-like appearance. There are five ponds along the salt trail, each pond can reflect several vivid colors depending on the salt concentration level. In low-to-mid salinity the ponds reflect a greenish algae color, during high salinity levels you could mistake the ponds for a pool of red wine.

Decades of pillaging the shoreline for salt did come at a cost. Much of the tidal habitat was destroyed due to salt production and its estimated that the San Francisco Bay lost 85% of its wetlands due to development, hunting and landfill.Restoration projects in the late 80s helped bring the wildlife and forage back to the Hayward shoreline.

The seasonal wetlands have become a favorite spot for migratory birds, who feed off the habitat’s many invertebrates. In many ways, the wetlands contribute greatly to the health and biodiversity of the bay.

.jpg)

-300x133.jpg)