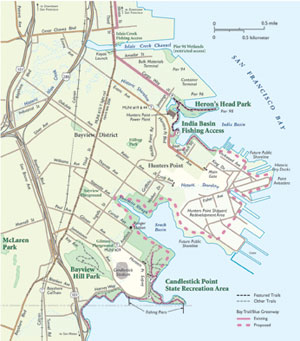

The vision is a compelling one: a string of healthy bayshore parks, well-used by people and wildlife, connected by a near-continuous stretch of regional trail, running from AT&T Park down along San Francisco’s often-neglected southeastern waterfront, through Bayview-Hunters Point, all the way to Candlestick State Recreation Area.

As I stood in Heron’s Head Park in the Bayview, at the foot of Cargo Way, on a sunny day this January, the feasibility of that vision seemed to vary based on which direction one faced. Look out toward the Bay, and you’ll see some of the city’s only remaining tidal marsh habitat, which hosts an astounding array of birds. At last count, over 100 species have been spotted from this tiny 27-acre park, home to the only nesting American avocets in San Francisco proper.

Turn around, though, and you’re face to face with the towering stacks of Pacific Gas & Electric’s aging and controversial Hunters Point Power Plant. One of the few existing stretches of the hoped-for trail connecting southeastern waterfront parks in this case from Heron’s Head to India Basin Shoreline Park runs right along the power plant’s fence. The plant’s roar and the churning water flowing out of its cooling system into the Bay make it hard to forget the long and sordid history of industry in this neighborhood.

Yet there’s still that view out to the Bay, and all those shorebirds which started coming back to this area when it was still an abandoned patch of debris and Bay fill, originally meant for a pier and then as a terminus for a never-built southern Bay bridge span.

And then there’s the work of nonprofits like Hunter’s Point based Literacy for Environmental Justice (LEJ), manager of the park since its inception in 1999, and Golden Gate Audubon, which first documented shorebirds’ returning to Heron’s Head and is now involved in other restoration projects nearby.

On my second visit to Heron’s Head Park in early January, the tide was lower than it had been a couple of days earlier, which meant that LEJ’s Ben Stone-Francisco and I could wade through the water over to the southeast shore, where resident American avocets would soon be nesting on raised areas in the tidal marsh. Most pairs begin breeding by late April, and newly hatched juveniles and their parents hang around the nesting ground until September. The spunky creatures were kind of pushy, considering their size; one chased off a western gull who had come a little too close for comfort.

I could feel the spongy pickleweed underfoot as I tried to keep from slipping on the uneven rocky surface below my rubber boots cumbersome yet necessary appendages. The partly submerged path gave us a closer view of the birds hanging out along the shore, far enough away to feel safe from intruders.

A slender snowy egret perched on one leg, head tucked under its wing. A few western sandpipers were on the shore also, while the coots, green-winged teals, American wigeons, and double-crested cormorants were diving for fish in the pool opposite the beach area near the “eye” of the heron-head-shaped park.

When we returned on the upland path to the park entrance, another cormorant stood on a raised platform, wings open in what Stone-Francisco called a Dracula pose, air-drying its feathers.

That kind of scene might become more common up and down the southeast shoreline, if planned parks and a “Blue Greenway” trail initiative become a reality. “The idea is to have the whole eastern shoreline connected through trails and parks,” says Arthur Feinstein, former conservation director at Golden Gate Audubon and now a consultant with an organization called Arc Ecology. “[We’re] working to make Yosemite Slough [just south of Hunters Point] into a place that rivals Crissy Field and the Presidio in terms of its attraction for the region and the community.”

- Much of the restoration work at Heron’s Head has been doneby local students, including this group of juniors from Sacred HeartHigh School. Photo by Benjamin Stone-Francisco.

A lot has changed at Heron’s Head since 1991, when Golden Gate Audubon members brought the area to the attention of the Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), the regulatory agency for San Francisco Bay. Birders found that the illegal fill at Pier 98, as Heron’s Head was then known, had attracted quite a number of migrating shorebirds. That meant the Port of San Francisco, which owns the parcel, could not remove the fill, which BCDC had been pressuring it to do.

In one sense, removing the fill would have been logical; this whole shoreline is made of fill. Heron’s Head, and much of Hunters and Candlestick Points, had been open Bay water just over a century ago. But the natural shoreline to the west had its own wetland habitats all obliterated in the development of the city. With the natural wetlands gone, the birds made the best of what they found in their place.

Under pressure from Feinstein and other activists, the port hired consultants to test the soil, capped the uplands with clay, then covered this surface with topsoil one way of handling contaminated land. It also hauled away more than 5,000 tons of concrete, asphalt, and other fill. Next came a fishing pier and a bird-watching station with cement walls to block the often gusty winds, along with a picnic area and walking paths on both sides of the shore.

“People walk their dogs; employees at the nearby warehouses and factories drop by for lunch, a walk, even a swim,” says Carol Bach, the port’s environmental and regulatory affairs manager. “It’s not unusual to see families fishing–the warm water from the power plant is an attractive habitat for fish.”

- A common loon with lunch in the waters off Candlestick Point. Photo by Photo by Peter LaTourette.

LEJ’s interpretive nature programs at Heron’s Head, also funded by the port, are the only such available in the area. And a new project called the Living Classroom will extend these programs further, says project director Simon Hurd. The proposed single story facility, with 1,500 square feet inside plus an outdoor meeting area, received a greenlight from the city last fall; building permits are expected in June. The building will use 100 percent solar energy and have a living roof planted with vegetation to minimize storm water runoff and increase energy efficiency.

The park’s 16 acres of upland habitat contain a surprising array of native plants, all thanks to recent restoration work: blue wild rye and red fescue, toyon, California coffeeberry, sticky monkey flower, and many others.

The work that went into those plantings has already made a big difference for local students, including those at nearby Malcolm X Academy. “[Our] partnership with Heron’s Head puts the concept of environmental responsibility and service learning into action,” teacher Heather Rothhaus says. “Over the past several years, I have taken my fourth-grade students to visit Heron’s Head about four times a year. We can walk to the park from school. We study the plants and animals, learn the risks to the park’s environments, what we can do to restore the park, and then do it. We are part of the transformation of Heron’s Head Park.”

Those immediate actions can have long-term effects. “The students take ownership of the park, [something that] will hopefully stay with them forever,” Rothhaus says. “In the beginning of the year, they knew nothing about the park. Then the discoveries happened. The random flower became the California poppy. Unnoticed birds became egrets or herons.”

But the habitat that brings fish and birds to the area also needs to be treated with some caution. Prominent signs warn people to limit their consumption of fish caught in the Bay, and some local residents are concerned that the measures to control pollution in the area have not gone far enough.

Tessie Ester, a resident of an adjacent housing project for nearly 50 years, remembers Heron’s Head when it was called Pier 98. Back then, it was a dumping ground and few dared eat fish from nearby waters. Ester, a member of Huntersview Tenants Association and Mothers Environmental Health & Justice Committee, still distrusts this area. She says she’d rather take neighborhood children to Crissy Field, which doesn’t have the same industrial history.

Opinions differ about toxicity at Heron’s Head—the successful avocet nesting augurs well for the area’s recovery but everyone agrees that other areas on the waterfront are quite contaminated. The former naval shipyard to the southeast of Heron’s Head is most famously so, but Yosemite Slough, farther to the south, also carries toxic baggage.

“The real issue is who’s responsible for all the contaminants in the slough itself,” says Feinstein. “No one is going to step forward and volunteer. There are some logical parties: the Navy for PCBs, and the City of San Francisco might also be responsible for contaminants. Yosemite Slough is the overflow for the city’s raw sewage.”

But even while those difficult questions are debated, people are working on the ground to make the parks and Bay Trail a reality people like LaConstance Shahid, who has worked with LEJ for three years and last year won a David Brower Youth Award from Earth Island Institute.

Shahid laments how little she knew prior to her advocacy work at LEJ about the ecology of Bayview-Hunters Point and its impact on her family and community namely that a wildlife habitat like Heron’s Head is an indicator of environmental health. She is now working at Candlestick Point raising native plants for revegetation in both the marsh and uplands at Heron’s Head Park, then later at Yosemite Slough.

“When kids come to work at the [native plant] nursery at Candlestick Point, they don’t want to get their hands dirty, but I tell them, ‘It’s just dirt and it washes off,'” Shahid says.

From stapling the tarp-covered floor in place to hanging the mesh awning, the entire nursery was built last year with sweat equity from young people ages 16 to 19. The teens also built the tables where the baby plants rest until big enough for planting at the monthly Heron’s Head Park restoration days. LEJ is well on its way to reaching its goal of 10,000 new plants, thanks to the Slough Youth Program.

One can see this native plant diversity in the uplands at Heron’s Head, where 3,500 native plants have been planted in the past year. The remainder of the plants are intended for local propagation and restoration of other wetland habitats along the Candlestick Point Regional Shoreline, including Yosemite Slough once it has been cleared of toxic contaminants.

Pier 94, two piers north of Heron’s Head, is another site where people are working to increase native plant diversity, says Elizabeth Murdock, Golden Gate Audubon Society’s executive director.

“We’re working to restore habitat for California sea-blite, a federally endangered plant species. At the same time we’re also doing it to create additional wetland habitat for shorebirds and waterfowl,” Murdock says. “This comes from the same vision that created Heron’s Head Park.”

The interconnectedness of habitat restoration and human access to open spaces is part of the Blue Greenway vision in San Francisco. Despite its small size, Heron’s Head Park—the only restored wetland park on the southern shore—plays a crucial role in this plan to open up green space in southeastern San Francisco. “We would connect Heron’s Head to the other green spaces and communities to make a network along that southern waterfront,” says Jeff Condit of the Neighborhood Parks Council. “[Heron’s Head] is one of the critical pieces.”

- Map by Ben Pease.

San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom threw his weight behind the Blue Greenway last fall by convening an official task force—a case of city leaders catching up with years of grassroots activism. Condit is hoping for quick results, in the form of new bike lanes on Hunters Point streets in May, as well as a long-term commitment to restoration. “Now,” he says, “instead of just coming from the bottom up, it’s also coming from the top down.”

Getting There

From 101, take the Cesar Chavez/Army Street exit. Go east on Cesar Chavez. Turn right on Third Street. Turn left on Cargo Way, which dead ends at the park entrance. To use mass transit, take #19 Polk bus to Evans Avenue and Jennings Street. Walk down Jennings to Cargo Way. The park is at the intersection of Jennings and Cargo Way.

For more about the park and the Blue Greenway, visit www.lejyouth.org and www.bluegreenway.org.

.jpg)