Like many rural California state parks, Anderson Marsh State Historic Park has suffered from poor funding, neglect, and the threat of closure. But now, in a twist of fate, the latest state parks funding crisis might prove to be the best thing in recent years that’s happened to this park with an ancient history.

Thanks to the support of a cadre of volunteers, the park has a new lease on life with a deal to stay open through June 2016 and funds to rebuild the only trail that leads to the park’s namesake, a marsh teeming with wildlife that is currently limited to water access.

Anderson Marsh’s revival is somewhat of an unusual case. Most rural California state parks languish in obscurity, with few visitors and thin community support to keep them going in tough times. But Anderson Marsh has been buoyed by those who value its history as one of the few sites in North America where artifacts attest to 12,000 years of continuous human settlement.

“This is not a wealthy county, but we had a big response,” said Henry Bornstein, a board member with Anderson Marsh Interpretive Association (AMIA).

The all-volunteer organization used the funding crisis to knock loose some funding from the state, win a foundation grant to make critical repairs, and put Anderson Marsh on the map. The 1,100-acre nature preserve protecting the habitat of a tule marsh and archaeological sites is located about 100 miles north of San Francisco and one mountain pass away from the famous wine region of Napa Valley.

And there’s more. California State Parks archaeologists teamed up with a university’s anthropology program to produce a new documentary film for distribution to Public Broadcasting Stations in Northern California, on the rich cultural resources here that the park protects.

Archaeological values

In 1982, the state acquired Anderson Marsh as the first and only state park purchased exclusively for its archaeological value, according to Leslie Steidl, a California State Parks archaeologist for the Northern Buttes District.

“It is the most important park that I take care of,” said Steidl, whose district represents one-fifth of California. “The archaeological sites represent the totality of human occupation in North America. It is unusual to have continuous human use in one area for over 12,000 years. It’s rare for the planet.”

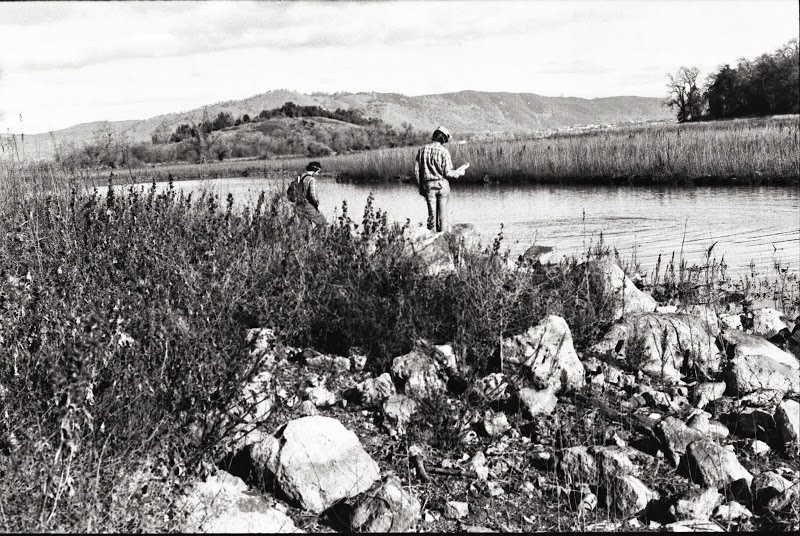

Before becoming a state park, Anderson Marsh achieved protection under the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 because of the work of a local archaeology student and resident named John Parker. Because of Parker’s fight to protect the area, the state purchased the property.

“Without his drive that could be another development,” said Steidl.

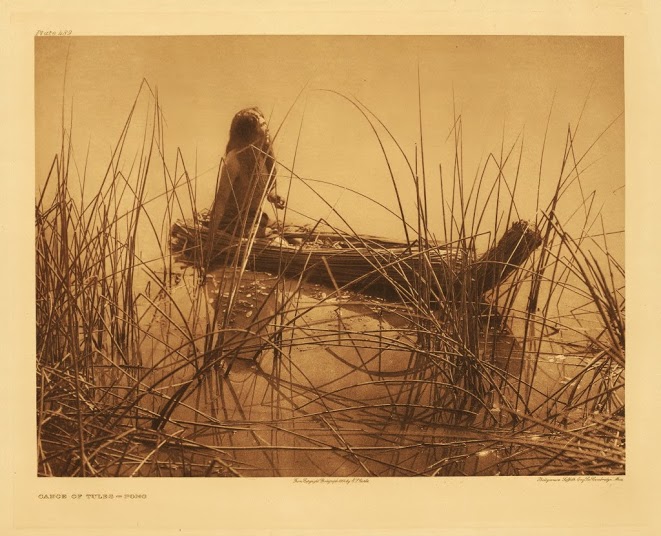

Parker rallied the community to stop a plan to build condos on the marsh and established a need to protect the cultural sites where the Southeastern Pomo developed the now world-renowned baskets, made arrowheads from obsidian, created rock art and traded beads from magnesite and clamshells. They also constructed canoes, dwellings, dance lodges, sweathouses, sleeping mats and clothing from the abundant tule here.

A homeland

Anderson Marsh was the homeland of the Koi tribe of the indigenous Pomo. The nearby island village of Koi, named Indian Island on park displays and maps, was the “capital for the Koi people,” said Dino Beltran of the Koi Nation tribal council. “My great grandfather was born on that island,” he added.

California State Parks was unable to outright acquire the island, located less than a quarter-mile from the shores of Anderson Marsh. But to protect the village, which holds special significance to the Koi’s descendants, the state purchased 1.5 acres of the island through a conservation easement. This area is not open to the public.

California State Parks is contracting with The California State University, Chico, Anthropology Department to produce a 26-minute film to highlight the rich prehistory of Clear Lake, the cultural history of the Koi and the unique and abundant natural resources of the area. Faculty and students in the university’s new National Science Foundation-funded facility will create the film with technology used by major Hollywood productions. They anticipate a fall 2014 release date to celebrate the park system’s 150th anniversary.

Chronically underfunded

I first learned about Anderson Marsh State Historic Park in December of 2012 when I spoke to Bornstein. At that time, Bornstein said that the park had been woefully underfunded since the 1990s. “The park’s incredibly rich in resources and basically ignored,” said Bornstein.

Anderson Marsh is not a developed park like the only other state park in Lake County, Clear Lake State Park. Yet it is a popular destination for school groups, senior groups, local residents and other visitors who come to learn about the park’s unique human history and view the abundant bird life including a large heron rookery. Bornstein and his wife Gae Henry retired and moved to Lake County from Berkeley more than six years ago. As birders and kayakers with encyclopedic knowledge of the cultural and natural history here, they think Anderson Marsh is one of the most beautiful spots on earth.

“We looked at this place and fell in love with it,” he said.

Bornstein and Henry are among 100 active volunteers who contribute thousands of hours to the park each year, and were on the ground and ready to respond when State Parks put Anderson Marsh on the closure list in 2011.

“We were No. 1 on the closure list. Alphabetically we were right there at the top,” said Bornstein.

Community rescue

To keep the park open past September 2011, AMIA’s board of directors, with the help of a local volunteer policing program, agreed to open and close the park gates on the weekends, take out the trash and pay to service the portable toilet. Then, they put a budget together and began to raise money to negotiate an agreement with State Parks to keep the park open. AMIA organized a benefit concert, joined the Chamber of Commerce and spread the word through community events and by talking to local businesses and groups like the Rotary and Lions Club.

“Lake County is not a wealthy county – in fact, it is a community afflicted with significant unemployment and relative poverty,” said Bornstein. “This makes the generosity of the community in supporting AMIA in keeping our park open even more amazing.”

AMIA more than doubled memberships and secured three years of pledges, from individual residents to conservations organizations and other educational nonprofits whose missions aim to protect Anderson Marsh. Other supporters include the local chapters of the Sierra Club and Audubon Society, Clear Lake State Park Interpretive Association, Lake County Land Trust and the Children’s Museum of Arts and Science.

After several months of negotiations, AMIA’s Board President Roberta Lyons signed a partnership agreement with California State Parks in April 2013. The agreement guarantees that the park will stay open through June 2016 and made the AMIA eligible to receive additional funding from the state under a legislative match program that’s been made available from $10 million in unreported state park funds discovered in the summer of 2012.

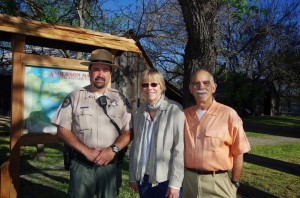

Having the backing of Clear Lake Sector Superintendent Bill Salata throughout the negotiation process was critical. It’s important to “work on the same side” with State Parks, said Bornstein. “We do not think of this as us and them,” he added.

Salata agreed. “We work well together,” he said of AMIA’s board of directors. “They are a small organization but they do big things with the help of local community.”

Natural abundance

Anderson Marsh’s rich cultural heritage stems from its natural abundance. Long before the name it acquired in the late 1880s, the tule marsh and wetlands here were so rich that as many as 1,000 native people were in settlement at a time, making Anderson Marsh one of the most densely populated areas of California in prehistoric times.

Here the waters of Clear Lake empty into Cache Creek and then snake through the park’s tule marsh, forming islands and a rich habitat for thousands of birds and other wildlife.

Trail access to the sites has been made better with new funding. The Cache Creek Nature Trail Boardwalk, newly repaired with grant funds from the California State Parks Foundation, the nonprofit that supports state parks, takes visitors along a wooden walkway to riparian habitat that otherwise could only visited by water. Tule reeds grow in thick stands along the shoreline.

“This was a major plant in the lives of the Native Americans,” said Henry on a recent tour of the trail.

They boiled and ate the roots, made clothing and swaddling for babies and bundled it to construct canoes, she said.

A trail to the marsh

State matching funds will help pay for restoring the popular McVicar Trail – the only land trail that leads to the marsh and the former Audubon McVicar Wildlife Sanctuary. This trail has been closed due to unsafe conditions caused by landslides and fallen oak trees.

“Given the fact that the name of the park is Anderson Marsh, it seems appropriate that some trail exists that actually leads to the marsh itself,” said Bornstein.

Additional funding has also allowed State Parks to assign a maintenance worker to the park — the first since 1995 —to do grounds keeping, trail maintenance and other routine maintenance.

“Having at least some park employee presence at the park on weekends is the first step to what we hope will expand into a full staffing of the park,” said Bornstein.

Under the new agreement, AMIA has promised to contribute $32,000 through a combination of in-kind and direct park expenses. The association will pay the bills for the park’s water, electricity, portable toilets and security alarm service for the 19th Century ranch house museum. It has reached about half its fundraising goal and must raise the remaining $17,000 by January 2014 to secure the matching funds from the state.

Bornstein is confident that community support will continue to pull them through.

“The people here truly love Anderson Marsh and are hoping that somehow, a way will be found to fund our state parks that goes beyond the current crisis mentality,” he said.

Christine Sculati is a Bay Nature contributor to our ongoing coverage of the state parks funding crisis, and also covers California state parks on her blog.