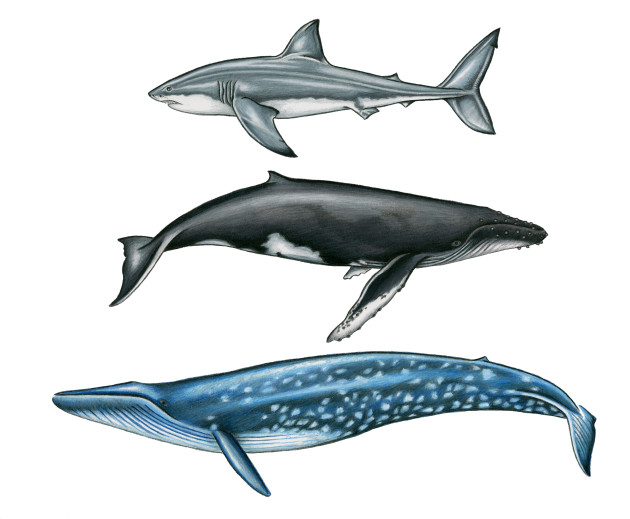

The Gulf of the Farallones and the Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuaries cover roughly 1,800 square miles off the California Coast and provide rich feeding grounds for populations of endangered blue, humpback, and gray whales, as well as some of the largest great white sharks in the world. They’ve been recognized since they received sanctuary status in the 1980s as vibrant ecosystems, abundant not only in marine wildlife, but in the benefits they provide to fishermen, researchers, tourists, and the the coastal economies that depend on them. They’re a success story for conservation – and a story, scientists and legislators say, could be better if it was bigger.

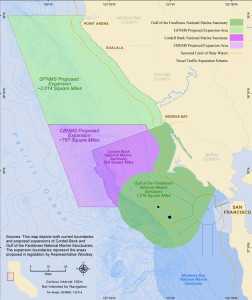

But growth hasn’t been easy. Senator Barbara Boxer and former Congresswoman Lynn Woolsey spent almost a decade trying to expand the sanctuaries, introducing legislation in each of the last four Congressional sessions only to have each effort stalled by Congressional Republicans. So in 2012 Boxer and Woolsey asked the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to pass a law administratively — a process that takes more time and incorporates public feedback, but also one likely to pass. The proposal now under NOAA consideration, which supporters hope to make final by the end of next year, would more than double the size of the sanctuaries, and protect the entire Sonoma County coastline and part of the Mendocino coastline to Point Arena, as well west to the edge of the continental shelf.

“It’s been a labor of love, and is still a work in progress,” said Mary Jane Schramm, the public outreach specialist at the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary.

An important part of the expansion process, Schramm said, has been communicating the value of the sanctuaries in public meetings, talking through concerns with residents of the most affected areas — Bodega Bay, Gualala, and Point Arena — and making sure they are addressed in a draft management plan. So far, she said, the expansion has received broad support from environmental organizations, coastal cities, and fishermen.

Sanctuary designation wouldn’t mean fisheries restrictions, says Schramm, but would protect the area from oil exploration and drilling. Although there are considerable shale deposits offshore, California has had a moratorium on offshore oil drilling for decades, and Tupper Hull, a spokesman for the Western States Petroleum Association, said the major oil producers that make up the WSPA “have no publicly stated interest in looking for, or developing whatever oil resources may exist in northern California.”

Sanctuary status could also limit coastal development and the construction of erosion-control barriers such as seawalls, which change the distribution of sand on the seafloor and affect aquatic animals that live in sandy habitats, such as halibut and Dungeness crab.

Although no coastal development or research project would be dismissed out of hand, Schramm said, the designation would subject such proposals to a review process. “It is a very special area and we don’t want to mess with what Mother Nature gave us,” she said. “It’s special because that’s how it evolved.”

The Farallon Islands lie 30 miles outside the Golden Gate, but they are a world apart. You can see them from the mainland on a sunny day, their wind-worn peaks rising above the water line like a row of shark fins. As the California Current flows south around Point Reyes, and spins around in gyres and eddies, it brings up nutrients into a burst of phytoplankton and krill, making the waters surrounding the islands a favorite spot for fish, birds, and marine mammals to feed.

That abundance underlies the desire to expand the sanctuary, Schramm said. “It’s amazing that these tiny marine organisms can sustain something as large as a whale,” she said. “One single blue whale will eat 4 tons of krill in one day. One whale, one day. There aren’t many places in the world that can do that.”

You only have to look up to see evidence of the abundance below. As many as 250,000 seabirds can be found breeding on the Farallon Islands and feeding in the surrounding waters. And they aren’t all local nesters. Albatross that live in northwest Hawaii fly all the way to the sanctuaries to feed, a journey that covers over 2,000 miles and takes 3 weeks. That journey might seem excessive, but as Schramm says, “it must be worth the commute.”

Cordell Bank, an entirely undersea sanctuary, lies just north of the Gulf of the Farallones. Its centerpiece is a seamount that sits at the edge of the continental shelf and rises to within 115 feet of the water’s surface. Its rocky face is abloom with sponges, corals, anemones, sea stars, and its nooks provide shelter for juvenile rockfish, a favorite snack of Coho and Chinook salmon.

Of course the ocean has no real boundaries. “We just draw lines on a map — the fish don’t see those lines,” Schramm said. “They have their own dynamics.”

Maria Brown, superintendent of the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, said she hopes to have a draft management plan completed sometime after Feb. 1, 2014. There will then be a 90-day public comment period with at least four more public scoping meetings to incorporate and address further concerns. Congress would have 45 days to object to the final proposal, Brown said, although historically Congress has not objected to administrative proposals. She said she’s optimistic that by the end of 2014 the sanctuaries will be more than double in size.

And while the final expansion may happen by administrative route, Brown credited Woolsey with keeping the idea alive. “Congresswoman Lynn Woolsey, who previously represented this area, carried the legislation and worked for years to bring about this National Marine sanctuary extension,” Brown said. “Achieving these important protections will be part of her legacy.”

Rachel Diaz-Bastin is a Bay Nature editorial intern.