Even on a weekday morning, Petaluma’s Shollenberger Park is a busy place. Joggers, dog walkers, parents pushing strollers, and bicyclists make their way along the main path, while bird-watchers raise their binoculars to catch a glimpse of a pied-billed grebe diving in search of its breakfast, or to watch a pair of avocets tending their nest.

History buffs can learn about this southern Sonoma County city’s commerce-driven past, and everyone can see a landscape that has been in transition, from better to worse and back again, for over 200 years.

Not bad for a park that started life as a dredge spoils site, and continues to be the receptacle for tons of mud dug up from the bottom of the nearby Petaluma River.

How did such a potential liability, tucked away behind a row of undistinguished office and light-industrial buildings, get turned into a magnet for walkers, joggers, bicyclists, and avian enthusiasts? The story could begin with a bit of river history, except that there isn’t one. A river, I mean. In geological or hydrological terms, the brackish Petaluma is actually a tidal slough, an arm of San Pablo Bay that extends approximately 14 miles up to the city of 55,000 people.

The landscape viewed by the Petaluma Valley’s native inhabitants, the Coast Miwok, was quite different from the one seen today. The slough meandered crookedly and formed a large oxbow just north of the present day park. The vast marshes and mudflats were a hunter-gatherer’s paradise filled with shellfish, shorebirds, and jackrabbits, not to mention tules and other useful plants. European explorers first made their way up the Petaluma in 1776, when Spanish sailors in a small boat conducted an unsuccessful search for an inland passage north to Bodega Bay. Sixty years later, Mariano Vallejo built a fort at the headwaters of Adobe Creek, which runs next to Shollenberger Park and empties into the Petaluma River. Soon, more Europeans began arriving, and by 1860, the river was being dredged and straightened, at first by Chinese laborers using shovels, reducing the distance from the Bay to the town of Petaluma by two miles. At the same time, farmers drained much of the surrounding wetlands, and the town grew into a major agricultural center.

As a result, the Petaluma River became the third-busiest inland waterway in the state, after the mighty San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers. An early-20th-century survey noted that in a single year 14,200 human passengers were transported along the river. So were 7,815 cattle and horses, 33,286 poultry, and 3,493,321 dozen eggs (it wasn’t for nothing that Petaluma billed itself “The Egg Basket of the World”), plus barges filled with grain, wine, pianos, caskets, trees, and more. However, as wetlands along the slough’s banks were diked off to accommodate agriculture, the slow action of the tides was unable to handle the increased silt load from ranching and farming upstream. Ships regularly ran aground, so frequent dredging became a necessity.

- Avocets are among the many bird species that frequent the centraldredge pond to feed and make their nests, which are often easy to seefrom the main path. Photo by Bob Dyer.

That’s how the slough became a river. In the 1950s, when the city tried to get the Army Corps of Engineers to take over the dredging, officials found out that the feds only scooped out “navigable rivers.” So, in 1959 then-Congressman Clem Daniels wrote a bill declaring that the Petaluma was no longer a slough. President Dwight Eisenhower completed the transformation with a stroke of his pen, and from then on, it was the Petaluma River.

Commercial traffic has largely shifted to the rails and freeway, and today pleasure boats make up most river traffic. But the few remaining barges mean that the Corps keeps paying for the dredging, which is normally done every four years. It’s up to the city to find a place for the 250,000 cubic yards of muck dug out of the river bottom.

Since the 1970s, that place has been the spot now known as Shollenberger Park. A 2.15-mile-long levee was constructed around a central pond into which the slurry of mud and water dredged from the river is pumped, which most recently happened last winter.

No one remembers exactly who came up with the idea of turning the dredge spoils site into a park. In 1985, the city decided that a small, county-owned recreational parcel a mile upriver from the dredge spoils site would make a good location for a fancy new convention center/marina/hotel complex. Sonoma County agreed to let Petaluma have the land if the city provided new public open space. Crews put a walking surface on top of the levee, and in 1995, the new Shollenberger Park was unveiled.

A few years ago, Bob Dyer was just one of the 400 or so local folks who visited the park every day. Newly retired, he thought that regular turns around the levee would help him drop a few pounds. But the walks aroused his curiosity. “For the first time in my life, I became cognizant of how many kinds of birds there are,” he recalls. Today, he’s become an expert on the park’s fauna and flora. He heads the city-sponsored volunteer docent program, leading the public and school classes on nature walks, and he’s active with the Petaluma Wetlands Alliance, a citizen’s group that keeps an eye on the park, organizes cleanups, and pushes for improvements and expansion.

A quick hiker could walk around the levee in well under an hour, but a tour with Dyer takes easily twice that long. He pauses frequently to check out the birds as well as to explain the varied habitats and the history of the park and its environs. Almost everyone seems to know him and stops to exchange gossip or tips about the latest avian sightings.

Dyer points out that there are actually numerous, intertwined habitats in the park and the surrounding area. The most obvious one is, of course, the central pond. At 160 acres, it’s slightly larger than Oakland’s Lake Merritt, but its ecosystem is quite different.

There’s no inlet or natural outflow, so in most years, the only water it receives is from the winter storms. These bring the water level quite high – in early spring the pond is an almost unbroken sheet of water. But by August, evaporation has reduced the pond to a few oversized puddles.

But that predictable Mediterranean wet/dry cycle is interrupted by the quadrennial dredging. In addition to a quarter-million cubic yards of mud, the dredgers deposit countless thousands of gallons of brackish water, along with invertebrates, fish, plants, and nutrients into the pond. “The dredging brings it back to life,” says Gerald Moore, chairman of the Wetlands Alliance.

- A flock of white pelicans visits Shollenberger every summer. Photo by Bob Dyer.

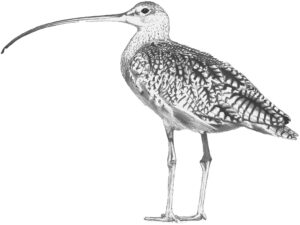

With all these complex changes, the pond is a Ph.D. thesis waiting to happen. Bird life is generally more abundant in the winter, with migrants like cinnamon and blue-winged teal, northern pintail, bufflehead, and goldeneye among them. A flock of white pelicans regularly visits in summer, and avocets, stilts, Canada geese, and a pair of nonnative but beautiful mute swans regularly nest here. A northern harrier and a red-shouldered hawk make frequent patrols. In all, more than 150 species have been seen in and around the park.

The levee trail’s overhead vantage point has given me some unique bird-watching experiences. A couple of years ago, I was walking along the levee when a pair of black-necked stilts suddenly bounded up from the grass at the foot of the levee. They screamed harshly as they careened back and forth, flying perilously close to my face. I was mystified until I looked down and saw two stilt chicks half hidden in the vegetation, their distinctive black and white markings just beginning to emerge from their downy plumage.

As Dyer and I follow a counterclockwise course around the levee, we come to the footbridge spanning Adobe Creek. The stream looks small and unimpressive, but it’s also a source of considerable local pride.

Twenty years ago Petalumans saw Adobe as a nuisance and used it as a dumping ground for old tires, household Creek appliances, and other garbage. The only visitors were local teens tearing up the streambed with their four-wheel-drives.

Then in 1984, Tom Furrer, a local biology teacher, had his students study the creek to find out what it would take to bring it back to life. An ongoing class project grew from there. The students planted thousands of trees, lobbied the city to rebuild the creek’s channel and tear down an old dam, and even started a steelhead hatchery at the school. The work, which continues to this day, has paid off. Not only is Adobe Creek much healthier, but the students’ energy and enthusiasm helped inspire efforts to restore other wetlands near Shollenberger Park and along the rest of the Petaluma River.

The main trail along the levee follows Adobe Creek for a quarter mile or so, and then curves left along the Petaluma River. The slough is a muddy brown no matter what the season, and it doesn’t have the variety of avian life that the central pond or nearby marshes do. In winter, Dyer frequently sees diving western grebe or rafts of scaup floating mid-channel. Across the river is a remnant of Petaluma’s industrial past—dilapidated buildings and half-submerged boats in various stages of disrepair. There’s also a small stand of eucalyptus that for the past two years has housed a colony of egrets and herons, who last summer built 30 nests and raised 50 chicks.

As we continue along the trail a new vista opens up. A broad mudflat, surrounded by low vegetation, lies before us. Dyer explains how Petaluma is again combining several projects—this time, parklands and sewage treatment.

- Raptors, like this juvenile red-shouldered hawk, regularly patrolthe park for prey, other birds or the jackrabbits that inhabit theupland areas. Photo by Bob Dyer.

Earlier this year, the city bought the 261-acre Gray’s Ranch, a former oat hay farm. About 45 acres will be used as a “polishing wetlands” for the new water treatment plant to be built nearby. Four new ponds will be planted with vegetation that removes contaminants as a final cleanup step, before treated sewage water is recycled or released into the river. The project is modeled after a marsh developed by the far-northern California city of Arcata, which pioneered the use of wetlands for sewage treatment in the 1980s. The ponds hopefully will become additional habitat for many of the species that now inhabit Shollenberger, and 3.5 miles of new trails will be constructed around the ponds and through the former farm’s uplands section, which provides nesting sites for Canada geese and habitat for jackrabbits, food for local raptors.

A few acres of hay farming will continue as a reminder of the land’s history. The mudflat, which was created when a levee broke during the 1998 El Nino storms, will be largely left to its own devices. But it will be a different ecosystem from the Alman Marsh. Because of the way the dikes broke, the land is flushed by the tides twice a day, so plants will have a harder time gaining a foothold here. That’s good news for the many species of shorebirds that forage on the bare ground exposed at low tides.

With the addition of the new property, there will be more than 400 contiguous acres of protected, publicly accessible wetlands in the south corner of Petaluma, one of the largest such parcels in the Bay Area. As the Coastal Conservancy’s Sam Schuchat notes, Gray’s Ranch is particularly valuable because the transition zone between the tidal marsh and uplands has been left intact-all too often it’s interrupted by freeways or housing developments.

Turning away from the broad panorama of Gray’s Ranch, Dyer and I encounter a more intimate landscape. A man-made water channel, bordered by thick cattails and bulrush, runs parallel to the final section of the levee. The channel serves partly as storm drains for city streets, and partly to accommodate overflow from the central pond. It’s a noisy place, thanks to the red-winged blackbirds and marsh wrens. On rare occasions, lucky hikers are treated to the sight of an elusive American bittern, Dyer says. As if on cue, we hear a rustling in the tules. There stands Botaurus lentiginosus, head stretched toward the sky and dark vertical stripes providing nearly perfect camouflage in the tall tules. The bird hesitates, as if to give us a chance to appreciate what we’re seeing. Then there’s a quick flash of movement, and it disappears, leaving behind a pair of spellbound bird-watchers.

.jpg)