Spiders — and their webs — hold a special place in our cultural mythology.

Tattered webbing is a feature of any horror flick, an icon of the evil that is lurking about with the spiders themselves often taking the role of vicious instruments of a higher, dark power. But then there’s also the great children’s novel, Charlotte’s Web, which gives a well-meaning spider a hero’s role for her mastery in manipulating events by writing messages in her webs. Clearly, we have ambiguous feelings about these small creatures, whose industry and skill can be both admired and loathed.

Download Our Printable Bay Nature Guide to Spidering!

In any event, it’s easier to appreciate the main work of most spiders — namely their web building — when you’re an order of magnitude larger than insect-sized. To see webs for what they are, chiefly as a strategy to catch prey, is to understand that a spider’s survival hangs on a thread of silk and what it’s able to engineer with it.

In constructing a web, a spider has created an ideal trap. Delicate and transparent, a web can seem ethereal; spiders often have to repair or rebuild from scratch every day. Yet, they are also incredibly strong and sticky, able to stop an insect hurling through space at a tremendous speed. A spider achieves these dualities by spinning with different types of silk, which emerge from silk glands in its abdomen by way of the spinnerets.

Indeed, the spider’s evolution into some 40,000 known species coincides with the diversification of silk and what that’s allowed in web designs, each type enabling a species to exploit a new ecological niche. Spider webs can be found in almost every imaginable place — even underwater — and have allowed spiders to populate every continent except frigid Antarctica. And there’s probably some spider out there working on how to exploit that last frontier (maybe with a penguin-snaring web?).

We’ve broken out five basic spiderweb designs (although there are more types) to give you a flavor of the range of hunting strategies spiders deploy. Any back porch can be an adventure in spidering if you know what to look for.

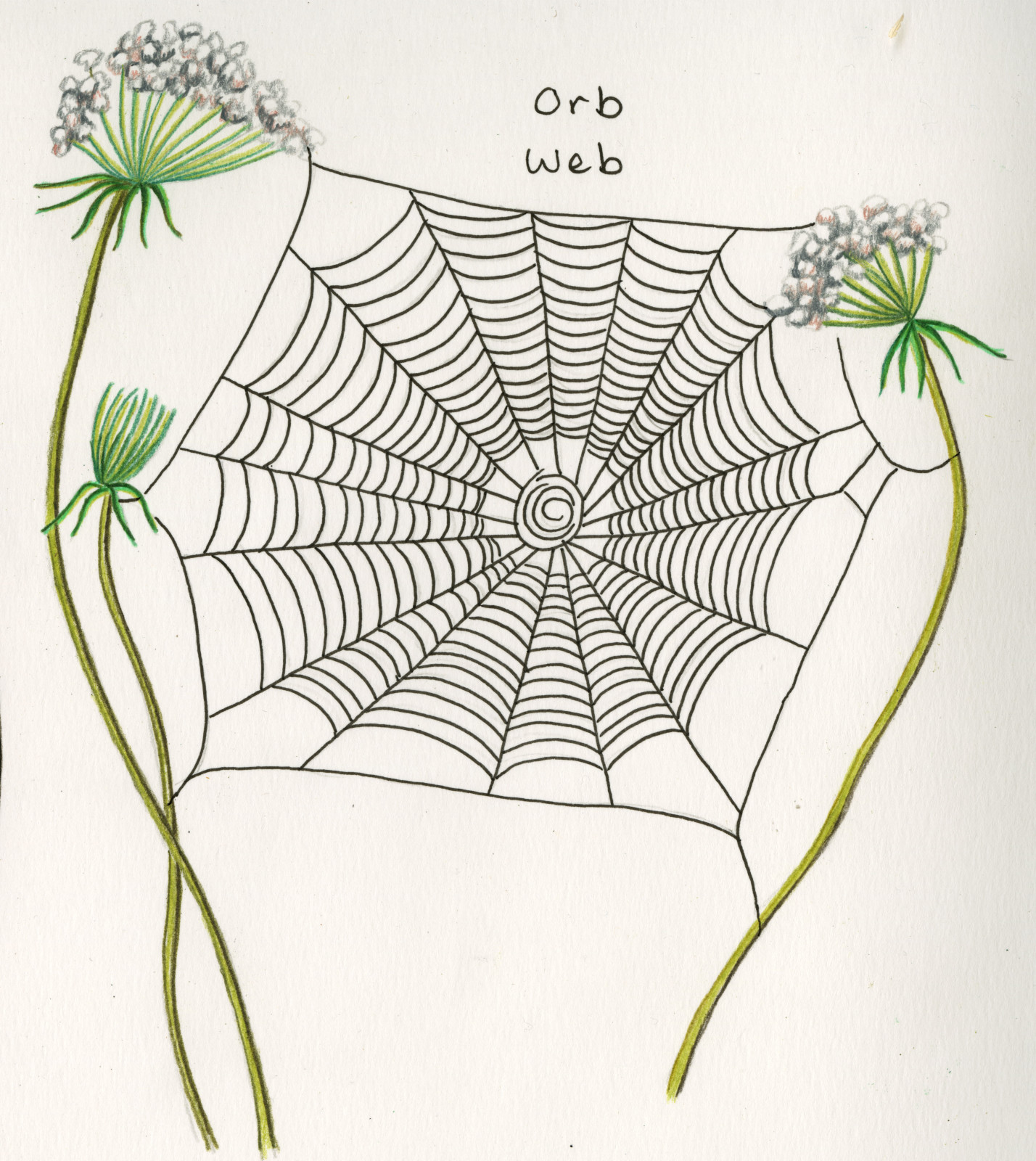

Orb Webs

Orb webs are the classic, wheel-shaped webs that have inspired everyone from engineers to poets to, well, designers of computer networks. They are primarily associated with their namesake, the family Araneidae, commonly known as the orb-weaver spiders, and have allowed spiders to fully enter vertical space. It’s speculated that orb webs came into being with the evolution of flying insects more than 100 million years ago.

The web consists of a durable silk frame made up of the outer bridge lines with internal anchor lines that are pulled downward to create spokes. An elastic capture thread is then used to make the spiral lines that connect the spokes together, giving the web the ability to absorb an oncoming insect. The spirals are bounded by sticky droplets to secure the victims. Additionally, some orb webs have extra flourishes — zig zags, spirals and bands — made up of bright white non-capture silk, detritus or even egg sacs. The purpose of these individual markings is unknown, although there’s a lot of conflicting theory around whether stabilimenta, as they are called, disguise the spider from predators or help attract its prey, or even (unintentionally) repel prey.

Crafting such a web is a highly cognitive endeavor, requiring a spider to size up a space, pick out anchor points and assess how much silk it has available. Orb weavers often redo their webs daily and have a memory for spaces they’ve used before. Orb webs can be viewed as highly functional predatory devices and when the weather cooperates, a spider can capture as many as 250 insects in a single day!

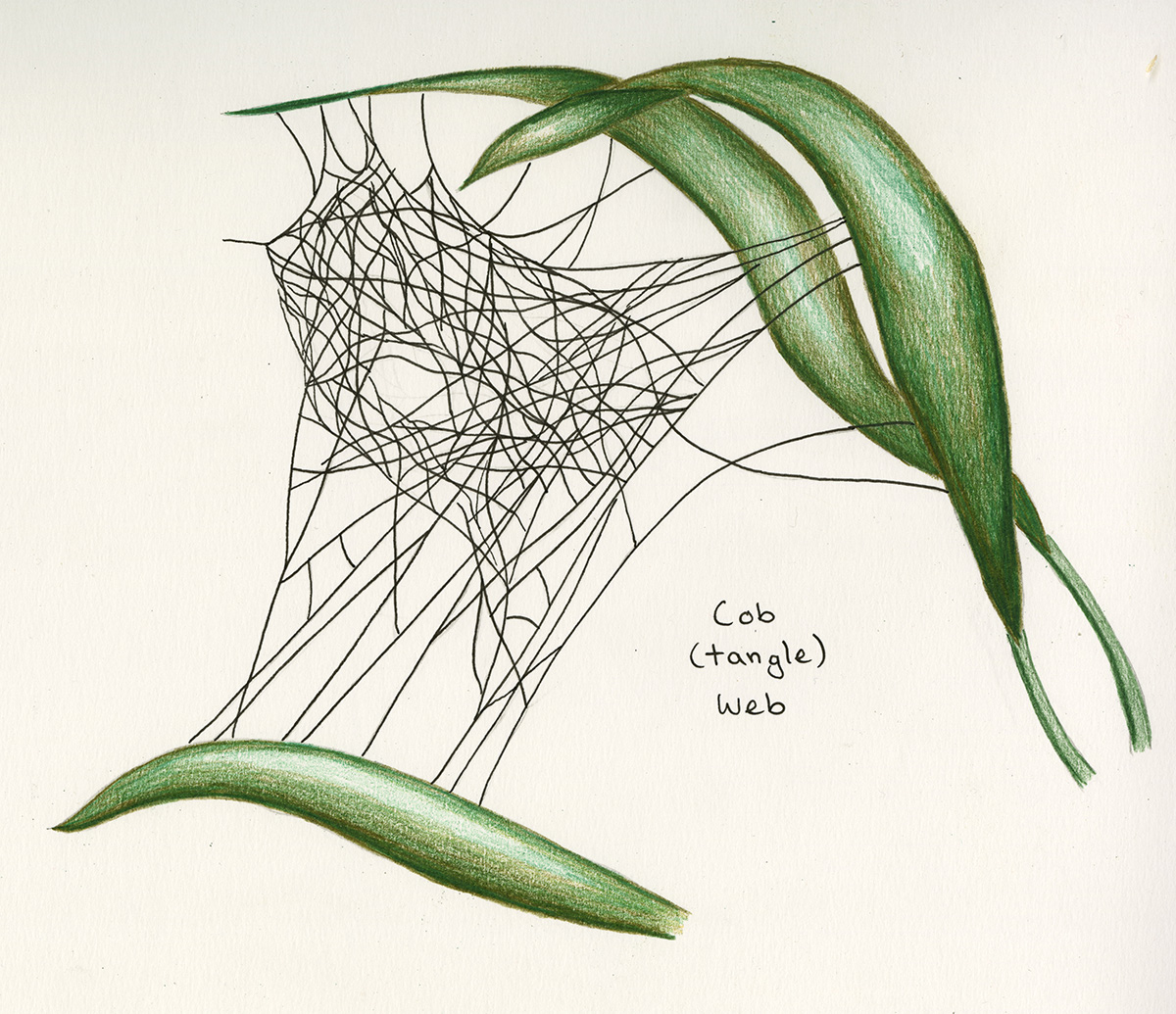

Tangled Webs

Tangled webs are also known as cob webs as they appear messy and shapeless. But they should not to be confused with the disused, dust-collected mats that appear in unswept rooms. Far from it, tangled webs are intentionally designed to be a jumble of threads, anchored to the corner of a ceiling or some other support beam — what better way to entangle an unsuspecting ant or cricket. Tangle web spiders, also called cobweb spiders, chiefly belong to the family Theridiidae and are known for building three-dimensional space webs. Among them, the common house spider and the notorious black widow.

The basic design is a littery web that is secured in space by a upper trellis with strands of high-tension catching threads that reach to a floor or substrate. On the end of these catching threads are sticky droplets and when an unsuspecting insect crawls across the thread, it breaks and the insect is stuck in the gum and drawn up into the central tangle as the thread contracts. Struggling only furthers its entanglement until the spider arrives, at which point the insect is finished off with a bite.

Interesting factoid: Some tangle-web spiders form groups of as large as a thousand to create webs stretching hundreds of yards to catch everything: flies to birds and other vertebrates. These social spiders have elicited the interest of evolutionary biologists studying the basis of altruism in group behavior.

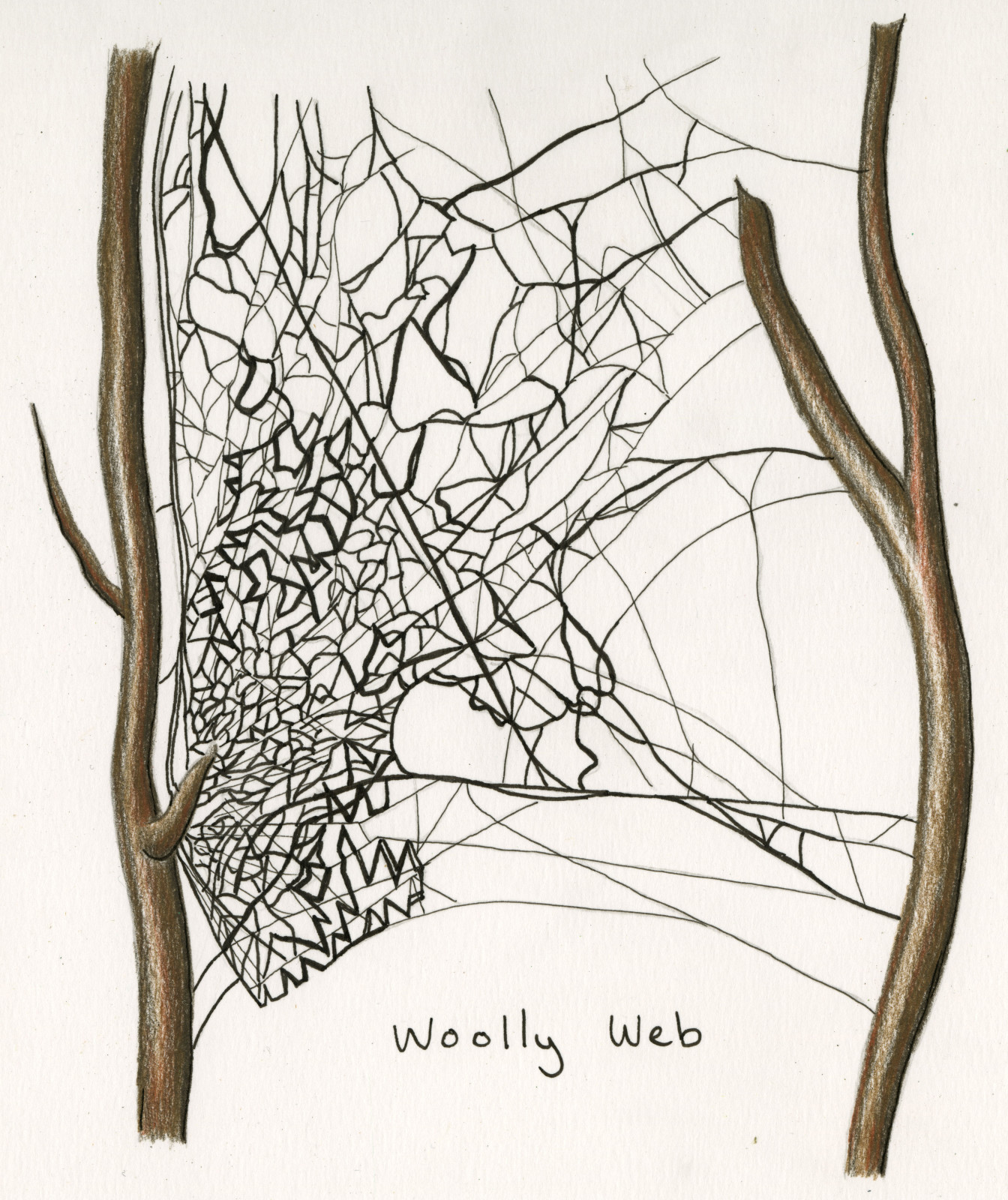

Woolly Webs

Woolly webs are distinctive not by shape as much as by texture. These webs consist of an adhesive silk that snags prey not with a sticky glue, but by electrostatically-charged silk nanofibers.

Spiders in the Desidae family, among others, construct these webs by extruding a gooey, raw silk through thousands of tiny spigots aligned along an abdominal plate, then using the bristles on a rear leg to comb it into woolly strands. The cribellum organ evolved early on in arachnids, and its presence (or absence) is a distinguishing feature in taxonomy. (For more about local spider evolution, read Bay Nature’s “Evolution’s Tangled Web.”)

The webs are often horizontal and are arguably not as geometrically perfect as, say, orb webs, but they get the job done. Insects that venture into the gauzy web are enveloped in a kind of silky cling-wrap. One of the best known woolly web builders, the cribellate orb weavers, lack venom glands and instead covers its prey with regurgitated digestive enzymes for later consumption of the liquified body. Yum!

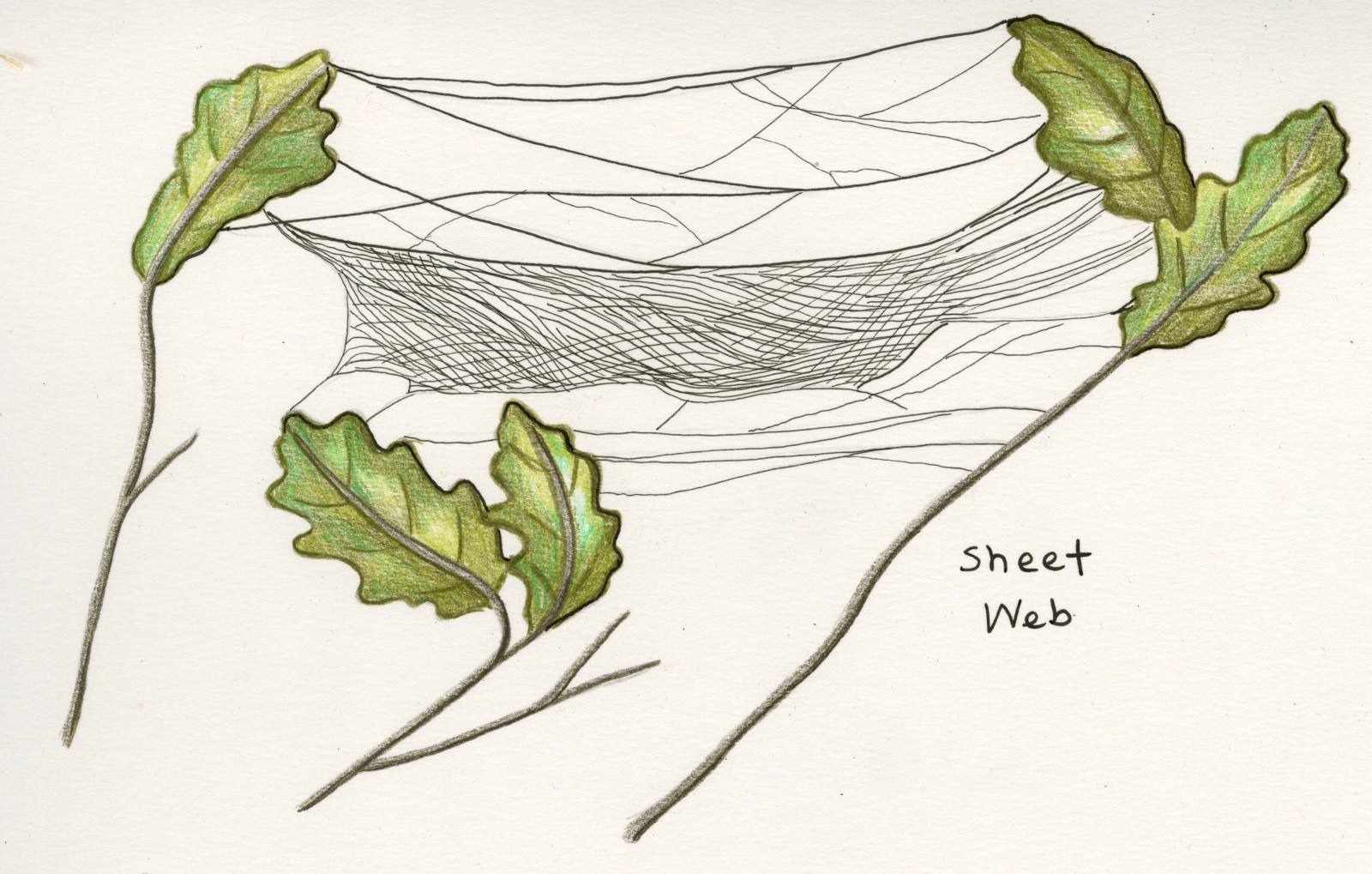

Sheet Webs

Sheet webs are slightly concave webs strung across bushes or blades of grass or branches of trees, sometimes dozens blanketing a single shrub. These webs act like a deadly hammock, crafted as a dense mass of threads with a maze of crisscrossing trip threads strung above the sheet. When an insect flies into one of these threads, it’s knocked off course into the net below where the spider lies in wait.

A sheet web is typically permanent and regularly repaired with the spider enlarging it as she grows. Sheet web builders may hang upside down below their sheets or they may create adjunct funnels where they eat and lay eggs.

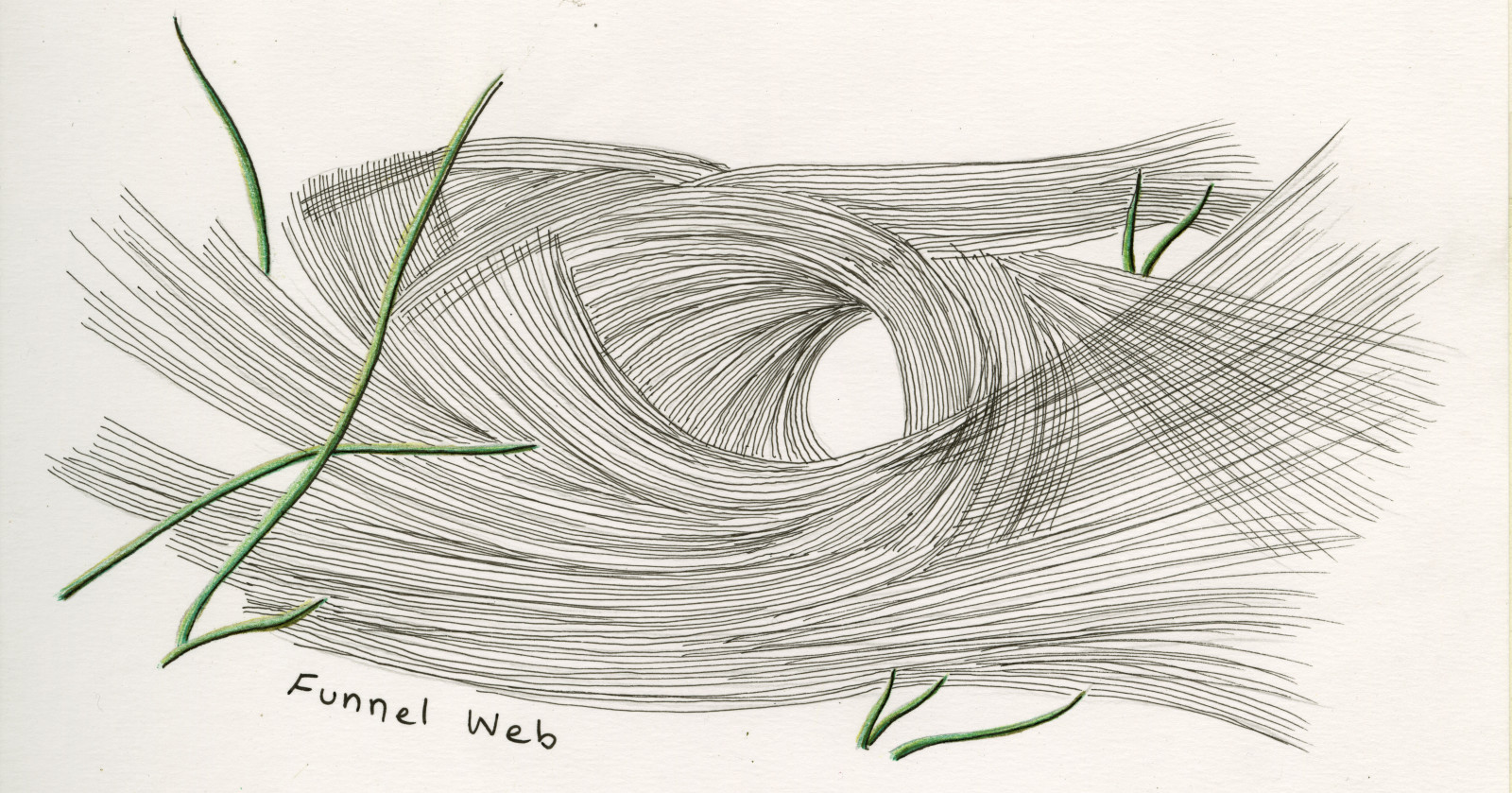

Funnel Webs

Funnels are worth mentioning as they are sometimes a main feature of a web design and can be quite impressive. A spider uses a funnel for a multitude of purposes: as a hideaway from prey or predators; to store eggs; and in the case of some males, to cohabit with a female spider and wait for mating time. Typically a sheet spans the exterior of the funnel, which is used to entangle prey, and the spider waits in its funnel retreat for the springy web to vibrate.

Some of the more impressive funnels are built by the family Agelenidae, known as the funnel weaving spiders with a common example being grass spiders. They are fast runners and their hunting strategy involves rushing out of their tunnels at a high speeds to deliver a venomous bite to their prey, after which they drag it back into their retreat to feed. They also have good eyesight and are sensitive to changes in the light, a defense mechanism to avoid predators.

Funnel-weaver spiders are almost entirely harmless to people, but they should not be confused with funnel-web spiders, a different family endemic to Australia with members that feature in many a “Deadliest Spider” list.

Get Up Close (and Personal) With a Spider

If the ancient spidering adventures of reporter Alisa Opar in the East Bay and Bay Nature’s guide to spider webs have you eager to examine spiders on your own, we’ve got a few more tips on what to look for and bring. Top of the list, the Field Guide to the Spiders of California and the Pacific Coast States is an invaluable resource.

There are also a few pointers for ancient spider seekers to keep in mind. “The interesting ones are much harder to find,” says Steve Lew, University of California, Berkeley entomologist. “That can mean a lot of poking around, which often puts you up to your elbows in poison oak. And you might draw unwanted attention from law enforcement.” (He declined to share any tales of the latter, unfortunately.)

The safest bet is to stick to trails, says Tilden Nature Area naturalist Trent Pearce. And not just because of the threat of poison oak. “The number one reason I tell people not to go off trail is because they might unknowingly trample turret spiders.”

Here are several basic tools that the pros carry with them in the field, in addition to spider guidebooks:

Pooter

Hand lens

Trowel

Headlamp or flashlight

Plastic vials or zip lock bags for safely inspecting specimens (Note: it’s illegal to collect any spiders from East Bay parks without a permit.)