This post about McClures Beach is the second-to-last post in Jules Evens’s yearlong quest to hike and write about every trail at Point Reyes National Seashore, which turned 50 years old in 2012.

Note: We just heard from reader Sandy Steinman that McClures trail was close don Dec 29, 2012 due to rock slides. For now, we’ll have to enjoy Jules’s words and photos while awaiting news on the trail’s reopening!

——

In every outthrust headland, in every curving beach, in every grain of sand there is the story of the earth. —Rachel Carson

Overcast, rain imminent, late afternoon, minus tide with Terry Nordbye.

These two short trails lead to one of the most dramatic and ecologically interesting stretches of beach on the peninsula—Kehoe Beach and McClures Beach. The walk from the end of one trail to the other along the outer beach is difficult and dangerous unless you time the trek to coincide with an extremely low tide. Three granitic “outthrust headlands” intersect the shoreline, jutting into the tidal reach from the coastal cliffs. This afternoon was a minus 1.5’ tide, so we decided to try to walk from Kehoe to McClures, about 3-miles northward along the shore.

The geology is well-exposed north of the entrance to the beach, bound on the upland margin by steep cliffs of Laird sandstone (of the Miocene) overlying granitic basement rock (of the Cretaceous). Even without plumbing the depth of their geomorphology, these cliffs lend interesting insight into the tumultuous and mysterious origins of the peninsula—rising-and-falling seas, and uber-tectonic tumult.

The rocky intertidal is all about real estate; “personal space” is sacrificed for a small patch of property, every millimeter matters. The granitic boulders that extend out into the intertidal off Kehoe Beach are covered with dense colonies of intertidal invertebrates. In the high intertidal the California mussel (Mytilus californicus) is the dominant resident, securing a foothold with its ability to attach to the rocky substrate. A glue-like secretion anchors the “beard,” or byssal threads, and allows the mussel to remain in place despite intense wave action. The “mussel-barnacle” zone rarely extend into the lower intertidal, because at lower elevations, ochre sea stars (Pisaster ochraceous) are highly effective predators of both mussels and barnacles.

Pisaster is not the only predatory invertebrate in the lower intertidal. Anemone’s are common here too, although they are passive (sessile) predators, laying in wait for whatever the tide sweeps into their tentacles. The tentacles are fully extended when submerged, and each contains spring-loaded stinging cells (nematocycts) that paralyze the prey, be it detached mussel, urchin, crab, or small fish. Two species of anemone are most common along these shores—the Giant Green Anemone and the much smaller Aggregating Anemone.

The low tide has exposed the subtidal community, and we search the smaller pools for some of the rare and seldom seen critters that can be found here. Nudibranchs, the inelegantly named “sea slugs,” are the most sought after because of their striking beauty—the butterflies of the invertebrate community. The common ones along our shore have names as exotic as their beauty—Hermissenda, Dialulua, Catalina, Aplysia. Our time is limited and we are exposed to incoming tide, so our search ends unsuccessfully. For an excellent introduction to these mysterious and gorgeous creatures, see California Academy of Sciences’ brief video.

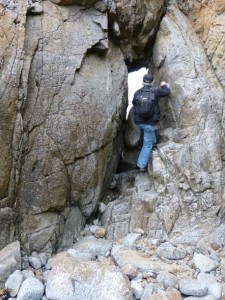

After crawling through a fissure in the rocks that separates Kehoe from McClures Beach, we find the tide pools and slippery rocks too daunting and too dangerous to continue, so we turn around, retrace our steps back to the car and drive to the McClures Beach trail.

The half-mile trail that descends from the McClures Beach Trailhead passes through an ancient dune system that was deposited by wind within the last two million years. The cliff faces, well exposed where the trail reaches the beach, are beautifully fluted by the persistent forces of wind and rain.

As I’ve discovered before, one of the pleasures of a desultory walk taken with open eyes and an open mind and heart is to happen upon unexpected or ephemeral beauty in familiar places. Such serendipity is sometimes amplified by its ephemeral nature.

At the end of the day, in the fading light, the shoreline and the skyline converge to provide yet another alluring panorama. As we’ve said to each other several times today, how fortunate we are to be in a place of such spectacular radiance.