East Homestead Road runs with aerospace-engineering-grade straightness for four miles through the core of Silicon Valley. It is bookended, depending on your interest, by two highways, the Lawrence Expressway to the east and West Valley Freeway to the west, or by two creeks, Calabazas to the east and Stevens to the west. (The highways run more or less on top of the creeks.)

One day a few months ago I stopped in the middle of a crosswalk at about the midway point of East Homestead and turned in a slow circle. The street before and behind me resembled a worksheet exercise in perspective: draw two parallel lines extending to a point at the horizon. The sun was high overhead, the concrete a perfectly flat plane beneath me.

It has been a joke for decades that Silicon Valley has no sense of place. There’s no skyline, little iconic architecture, nothing to snap a selfie in front of to give you a sense that you’re here in the dynamic beating heart of one of the unique moments in human history. In The Nudist on the Late Shift Po Bronson describes an ABC Nightline television crew coming out to capture the exciting new things happening and then wandering aimlessly in a search for an appropriate “establishing shot” to tell the viewer where they are. “The irony was acute,” Bronson writes. “The industry that gave us the Macintosh smiley face and a screenful of icons that make computers touchy-feely familiar never coughed up an icon for the whole shebang.” When Santa Clara hosted the Super Bowl in 2016, CBS promotional photos showed the Lombardi Trophy in front of the Golden Gate Bridge 45 miles away.

“As a human landscape, it’s a crushingly boring sunny suburban slab of freeways, fast food, traffic, and long smoggy boulevards of faded retail sprawling out to endless housing developments of sand-colored stucco boxes,” wrote Ken Layne in a 2010 Gawker essay about walking Silicon Valley. “It’s Phoenix with milder weather, Orlando minus the mosquitos.”

Why does Silicon Valley looks so particularly bland? There’s the obvious wide streets, soulless office parks, big box retail, and earth-toned houses. But there’s another cue that may go less noticed: the nature of its streets. People navigate by trees and hills as much as by concrete and stucco. And if you stand in this intersection on East Homestead, or any of the thousand intersections in Silicon Valley, you look down a suburban street absent contour or texture at a row of globally ubiquitous mass-produced trees.

I happened to be looking at a dozen London plane trees. The London plane tree is a hybrid of the oriental plane, Platanus orientalis, and the American sycamore, Platanus occidentalis. It is by far the most common street tree in London. It is a common street tree in Rome, Buenos Aires, and Sydney. It is the most common tree in Szczecin, Poland. It is the tree that lines the Champs-Élysées in Paris. It is the most common street tree in New York City. It is the tree in the orchard that separates the California Academy of Sciences from the de Young Museum in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. It is the tree I can see out the window of my office in Berkeley. The London plane is the sand-colored stucco box of trees. If you are standing in an otherwise featureless intersection and looking at a row of London plane trees you might be in any city on Earth. Instead of rooting us in place the trees of Silicon Valley free us from it.

“Why have people moved across the world spreading a similar ecosystem type?”

Ecologists have coined a term for this phenomenon: ecological homogenization. The more influence people have on the world, the more the world’s urban ecosystems are coming to resemble each other more than they resemble the natural areas that preceded them. You can see this in soil microbial processes, which in one study of six American cities slowly grew to resemble each other. There’s evidence city microclimates across the continent are becoming more similar as people choose the same plants, and neighborhoods have a similar mix of trees, shrubs, grass and pavement. Since every city is more or less built from the same materials and is exposed to similar atmospheric chemistry, city soils are more or less polluted with the same heavy metals while urban soil pH is slowly rising from calcium leaking out of concrete and drywall. There’s evidence that even the shapes of urban water bodies are converging. In a 2014 paper in the journal Ecosystems a team of researchers reported that the hydrography of residential neighborhoods in Miami and Phoenix is more similar to each other than to the hydrography of the Sonoran Desert and Everglades natural ecosystems that they replaced. “You sit there in Phoenix,” says Peter Groffman, an ecologist at the City University of New York Advanced Science Research Center, “and a lot of people have moved there from the northeast because they’re allergic to tree pollen. And then they planted all these trees. Pollen counts in Phoenix can be really high. Why have people moved across the world spreading a similar ecosystem type?”

Three hundred years ago, to walk from the site of the modern-day Apple Campus in Cupertino to the bayshore site of the modern-day Google headquarters in Mountain View would take about four hours. You would start in an oak savanna at Calabazas Creek on the west edge of Tamien Ohlone tribal lands, walk west through oak woodland and chaparral to Stevens Creek, then turn north to follow the waterway through oak woodland and oak savanna, until the water fanned out into willow woodlands and the lazy water of the South Bay near the Ramaytush Ohlone village of Puichon.

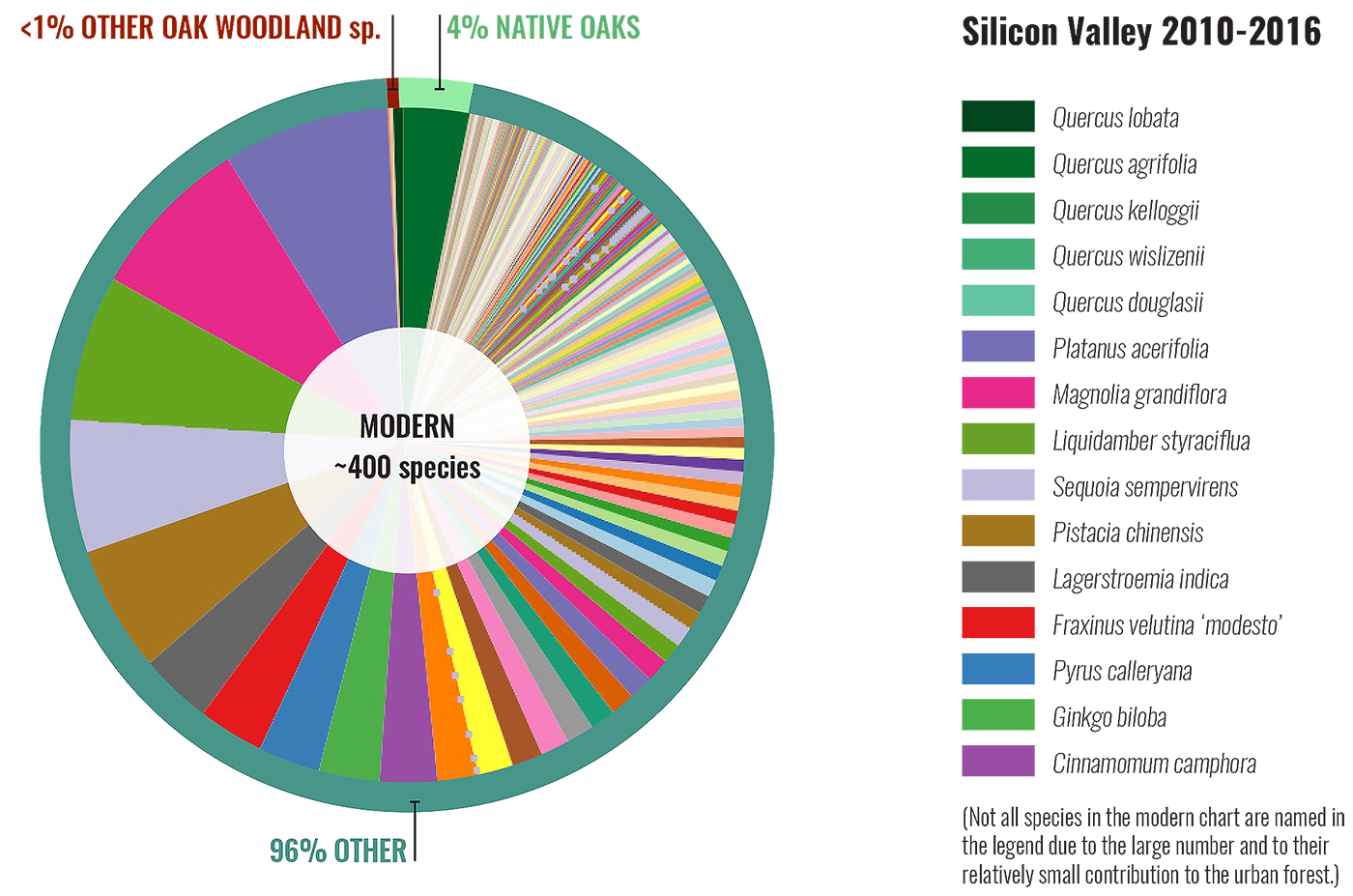

In the entire Silicon Valley you would have encountered fewer than 20 species of tree. Lord among them would have been the oak. As recently as a 1850, according to a recent report from the San Francisco Estuary Institute, 80 percent of the trees in Palo Alto, Mountain View and Cupertino were oak trees. Another 13 percent of the trees were those commonly found alongside oak trees in oak woodlands: buckeye, madrone, sycamore, and California bay laurel. Willows, alders, and redwoods rounded out the final 7 percent.

Oaks created the place. Postcards from San Jose in the early 1900s show farmers standing in the shade of skyscraping oak trees. Spanish explorers called Silicon Valley the “plain of the oaks.” The Peninsula is still home to two Roblar Avenues, a Robles Drive, and a Robles Park, as well as the North Fair Oaks and Menlo Oaks neighborhoods of Menlo Park.

Most of Silicon Valley’s oaks were valley oaks, the largest and longest-lived of North American oak trees. They grew tall and towering, and “in such numbers,” a one-time gold miner named Thaddeus Kenderdine wrote in 1898, “that I wondered the farmers tolerated them.”

The farmers, of course, did not tolerate them. Valley oaks thrive in the rich soil of creek floodplains, which happens to be prime agricultural land. The farmers cut the oak trees down and replaced them with fruit orchards. Later developers paved over the orchards and cut down what oaks remained to build sprawling residential neighborhoods. Over 150 years, scientists at SFEI estimate, there has been a 99 percent decline in valley oak populations in some parts of Silicon Valley.

Recently, to try and get a sense of the modern valley’s nature, I walked over the buried oak woodlands from the new Apple Campus in Cupertino to the Googleplex in Mountain View. On the default view of Google Maps there were only three green areas on this entire 10-mile route: two school baseball fields and a playground. I saw no valley oaks. As I walked I tallied coast live oaks in the neighborhoods and kept it to a single sheet of paper. But once I was looking it was also easy to see the green in this gray, flat, sprawling corner of the world. There are trees everywhere. There are trees by the thousands. And in place of lost valley oaks we have invited in an absolutely staggering increase in tree diversity.

Today there are something like 400 species of trees in Silicon Valley. Oak trees, mostly coast live oak, make up about 4 percent of the total number of trees. London plane, magnolia, and sweetgum make up about 8 percent each. Surprisingly the percentage of canopy itself hasn’t changed particularly over the centuries. SFEI scientists estimate the canopy cover in 1850 Silicon Valley as ranging between 25–60 percent. They estimate that it now averages 30 percent in the urban areas of the valley. Imagine the potential, they conclude, if we started thinking about how to make the best use of that canopy across the entire region.

“This is an area of literally hundreds of thousands of acres around the Bay, and probably a million or more trees,” says Robin Grossinger, a historical ecologist at SFEI and co-author of the report Re-Oaking Silicon Valley: Building Vibrant Cities With Nature. “In the Bay Area we’ve done a pretty remarkable job protecting the hills and the Bay and the baylands, of protecting and preserving a greenbelt and a bluebelt. But we’ve tended to ignore the gray area in between, just leaving it to be a blank from a conservation perspective.”

We’ve all stared at Google street maps enough to internalize a color-coded message about developed areas as gray wallpaper. But gray-blue-green isn’t a mirror of real-life. Even in urban Mountain View in 2017, vegetation accounts for more than 40 percent of the land cover. “It’s only recently with urban ecology that they’re starting to notice there’s a lot of biodiversity in cities,” says Erica Spotswood, an ecologist at SFEI and the lead author on the Re-Oaking Silicon Valley report. “Can you help support regional goals by supporting conservation goals in cities, so the city isn’t just this giant gray blob that everyone has to move around?”

The realization that city nature exists led ecologists quickly to the realization that people’s choices matter. We’re not just homogenizing the landscape, says University of Washington urban and environmental planner Marina Alberti; cities could be driving rapid evolution in urban plants and animals. In a 2017 article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Alberti and colleagues reported that they’d identified an urban “signature” in the changing phenotypes of more than 150 species. “In cities today we are running a planetary experiment of Earth’s evolution,” Alberti told me recently. “The findings received very much attention not only among scientists but by a diversity of people with great curiosity about this amazing power of our species.”

Ecologists and planners want to use that power to make cities a little softer for nature. Urban greening initiatives like stormwater runoff systems and low-impact development lead the way. Books and magazines encourage pollinator gardens and backyard wildlife gardens. But re-oaking Silicon Valley would move the field one step beyond the neighborhood to try restoring a shared ecology to an entire region.

“There aren’t a lot of people thinking about how to restore lost ecosystems in cities,” Spotswood says. “SFEI has done a lot of thinking about historical ecology and how to use it to inform what we do in the future. And we’ve done that for a lot of other systems, but not for cities.”

On a late-fall Tuesday morning the new Apple campus in Cupertino was an overturned anthill of fluorescent-vested workers. At the place where North Tantau Road crosses Calabazas Creek two of them were having a cigarette break and staring into their phones. The three of us stood over the drainage culvert, under the shade of a coast live oak tree. Across the street, in the median, were several dozen more live oaks. The campus itself contains hundreds, maybe thousands of oaks behind a tasteful green perimeter fence. It’s byword in the arborist trade the way Jobs and Apple cleaned out every nursery in California to acquire enough leafy adult trees for the campus.

Like the Pyramids or the Taj Mahal, the photogenic beauty of the new Apple Ring relies on selectively cropping out the surroundings. In an interview with Wired writer Steven Levy, Apple CEO Tim Cook made a clear distinction between the 9,000 trees they’d planted and … whatever it is on the other side of the fence: “When I really need to think about something I’m struggling with, I get out in nature,” Cook said. “We can do that now! It won’t feel like Silicon Valley at all.”

Apple’s signature monument was dropped into a perfectly rectangular Silicon Valley neighborhood. It is a block so large as to allow Cook to forget its surroundings, landscaped in a way to reflect the oak woodlands of old. But it is a rectangular block in a sea of suburban sprawl nonetheless. One way to look at the Apple campus is to stand on the sidewalk and look in, where there are thousands of oak trees, and then turn around and look across the street at the neighborhood, where there are none. Another way is to look at the oaks of the Apple campus as the heritage-honoring choice of a famously micromanaging CEO for whom money was no object, and the ecologically generic American elms and sweetgums across the street as the democratic choice of the less prosperous.

“Oftentimes it’s that bigger priority values are trumping environmental values.”

I left Apple and walked west on East Homestead for several miles. There were hardly any oaks, and hardly any people. Silicon Valley is, as Layne writes in his Gawker essay, an “anti-pedestrian landscape.” Walking in a straight line on a flat sidewalk I passed retail box stores, two-story apartment complexes, and single-family ranch-style houses ripped from the set of HBO’s Silicon Valley. I walked past Homestead High, home of the Mustangs. I walked past Cupertino Middle School, home of the Bears, who were having PE class.

In place of oaks I walked past elms, magnolias, sweetgums, planes, redwoods, firs, gingkos, cherries, pears, olives, pepper trees, water gums, strawberry trees, and countless others. I stopped in a yard to admire a small pomegranate tree, slouching toward one spectacular fruit that hung like a merry red Christmas ornament. It is relatively easy, if you are Steve Jobs designing a campus with 9,000 trees, to dictate that many of those trees are ecologically appropriate oaks. But how do you ask a neighborhood to make ecologically appropriate decisions when it is each person’s right to prefer a fruit tree in their yard? What if this landscape reflects not so much a knowledge gap — if only people knew what trees were here originally, they would prefer them to generic interlopers — as it is that with everything else in the world to worry about most people just don’t want to think that hard about trees?

“If you ask people they will express pretty strong environmental values,” says Kelli Larson, a sustainability scientist at Arizona State University who studies attitudes toward urban ecology. “Oftentimes it’s that bigger priority values are trumping environmental values. These other things — including convenience, aesthetics, leisure, and family — are bigger priorities for people.”

A few years ago Larson, Peter Groffman and colleagues surveyed people about urban nature in the same six cities across America where they’ve found soil microbe communities are converging. They found that the priorities for a residential landscape seem universal. In all six cities people wanted beauty first, low-maintenance second, and “local cultural values” eighth out of eight. Ecological benefits may be the worst possible argument you can make in trying to sell native plants, Larson says. “It’s shown that traditional approaches to environmental education have not really been a good path to getting people to do what you want them to do,” she says. “So what I would not do is say, ‘But it’s native!’ People just don’t care. You’ve got to make it desirable somehow.”

They have also found, though, that what people perceive as beautiful and low-maintenance is not absolute. Therein lies the urban ecologist’s opportunity.

“Restoring elements of oak woodland ecosystems to urban environments could make California cities less similar to cities in other parts of the world.”

The London plane tree has spread around the world for a reason: it is the perfect tree for people who don’t want to care that much about trees. It is tall. It grows easily. It provides shade. It is easy to sculpt it to avoid power lines. It doesn’t bear annoying fruit. Its bark “exfoliates” regularly, allowing it to filter pollution — plane tree lore says it caught on originally in London at the height of the Industrial Revolution, when people noticed it scrubbing the grimy air. It changes colors at the right time of year. It drops nice, big, beautiful leaves that in autumn you can rake and pile and stomp with a satisfying crunch.

The argument for the oak tree is more intellectual than sensual. A coast live oak sequesters more carbon than many other common urban trees and twice as much as a London plane, according to data from the Center for Urban Forest Research Tree Carbon Calculator. Oaks tolerate drought yet draw up more runoff than many other trees in heavy rain. Oaks host diverse California wildlife. In the re-oaking report Spotswood paid close attention to the benefits of oak trees to acorn woodpeckers, oak titmice, and mournful duskywing and California sister butterflies. Finally, oaks are historic. The valley oak, in particular, only grows in California. “Restoring elements of oak woodland ecosystems to urban environments could make California cities less similar to cities in other parts of the world,” the report says, “reinforcing a distinctive identity and adding character that could complement local landscapes and architecture.”

After walking through the neighborhoods of Silicon Valley for several hours I crossed the West Valley Freeway on a pedestrian bridge and descended to Stevens Creek. The creek itself runs sluggishly through a deep-cut channel. It is lined with coast live oak trees, and a running and biking trail along its edge has been landscaped with native plants. After two hours in the sense-dulling suburbs the particular dusty late-summer look of the trail, the oaks, and the muddy creek felt inescapably Californian.

I walked north along the creek for a while until I reached a spot where the bank had eroded. Out of the oaks and matilija poppies a bright orange detour sign pushed me out onto the street, past an auto parts store, a Starbucks, a Burger King, and a towering row of sweetgum trees and redwoods on a grassy lawn. As an example of human aesthetics shaping a landscape, redwoods, once vanishingly rare on the valley floor, now account for about 4 percent of trees there.

Beyond the detour and a series of canopy-level overpasses a wide, algae-lined culvert funnels Stevens Creek under Highway 101 and into the Bay. At La Avenida I turned away from the water toward the future site of one of Google’s new campuses, Charleston East.

This recent push to re-oak Silicon Valley originates in the Googleplex. As the tech company’s real estate holdings increased over the last few years, its ecology team went looking for scientifically sound green landscaping options. They found SFEI, where Grossinger’s group had been studying the historical ecology of Silicon Valley for a decade, and asked for guidance. The result was a project called Resilient Silicon Valley, and then the more technical Re-Oaking Silicon Valley report. Google also sponsors the community group Canopy, which leads neighborhood tree care, planting and citizen science efforts in Palo Alto, East Palo Alto, and Mountain View.

(Disclosure: Google also sponsors Bay Nature’s annual fundraising event.)

“We’re not going to create oak savannas,” says Google Ecology Program manager Audrey Davenport. “But we actually can bring the function of an oak ecosystem back to these places. We can help wildlife. The re-oaking guidance has been great because I can turn to landscape architects and say, ‘Here’s what we want to see in your designs,’ and they can work with that.”

“The thing about ecology is it doesn’t optimize at the scale of a commercial building.”

Google has incorporated re-oaking into the designs for two of its new campuses and converted 50 acres of its existing campuses to native landscaping. The Charleston East design calls for planting 383 native trees, mostly oaks. Given their weight in the world, it might feel as if Google and Apple have chosen oak trees, so then what space is left for anyone else to fill. But the nice thing about walking is it acts as a corrective to the sense of scale that imagination suggests, in my case by revealing just how vast is the un-oaked valley between the two tech giants. A successful re-oaking of Silicon Valley hinges on what happens there, in the great gray suburbs where new trees are chosen one property owner at a time. Will the tech companies influence their residential neighbors — schools, suburban developers, office parks, homeowners — to choose oak trees instead of London planes, sweetgums, or magnolias?

“The thing about ecology is it doesn’t optimize at the scale of a commercial building,” Davenport says. “How do you think about ecology across a broader region? I think there’s good momentum toward moving it away from capital projects to district-scale investments. Those things that really make a place livable and create quality of life for people.”

On a strictly aesthetic level — the level at which people are likely to make decisions about what landscaping they’d like to copy — both homeowners and landscaping crews can find native landscapes challenging at first, says HT Harvey restoration ecologist Dan Stephens, who consulted on the Charleston East campus. Native plant landscapes tend to be messier and busier — well, they’re designed to mimic wild spaces, which are messy and busy. Oak trees, willows and California wildflowers wake people up with year-round color and texture, Stephens says. Because the plants are native you get more birds, bees and hummingbirds, and more seasonal change, so there’s more constant movement. Songbirds visit at different types of year, so there’s more sound.

“We’re taking the long view,” Stephens says. “Initially people may not understand, but the more of these landscapes you put out there, the more people will get used to them, and eventually they won’t want the conventional pattern anymore.”

Once, over lunch, I asked Grossinger and Spotswood what re-oaking success would look like. They thought about it for a minute. Much of the urban forest in Silicon Valley right now is 50 or more years old. Those trees will need to be replaced soon anyway. Maybe success looks like incremental small changes, one replacement oak tree at a time, for two decades.

“It’s great if you can take your kids camping on the weekends but what really matters is local, nearby nature that is accessible on a daily basis.”

At a recent ecology conference, Spotswood spoke about oaks in developing the identity of the city of Oakland, and how they’d mostly been cut down, and what that meant for people living there today and their ability to benefit from urban nature. She talked about sending her daughter to preschool in a mostly treeless neighborhood, and about trying to develop her daughter’s love of nature in the city where they spend most of their time. “It’s great if you can take your kids camping on the weekends but what really matters is local, nearby nature that is accessible on a daily basis, like in our urban gardens,” Spotswood said. “If we could bring back the oak trees…”

Twenty years ago scientists viewed urban ecology as a great unknown. Or less than that, as futile. But Alberti says it’s increasingly apparent that nature in the city is the best way we have to re-connect people to the world around them. “Humans are a dominant species on this planet,” Alberti says. “They’re going to determine in many ways the future of the planet. Whether they will be able to actually help — to evolve the planet in a direction that is mutually beneficial for our species and other species — really depends on whether we understand the power we have.”

Alberti says that after her paper on how cities might drive evolution, she started to think about cooperation among species. Humans building cities are just like other organisms constructing their niche, she says. Every species alters the trajectory of the planet in some way great or small. Maybe if we brought some nature back it would remind people of our potential to do good.

“I have been thinking about this idea,” Alberti says. “If microbes were able to transform the planet into a more livable planet, what could humans do to outperform microbes?”

Nonetheless it is hard to imagine a more complicated partner in a cultural shift toward honoring place and heritage than Silicon Valley. Google and Apple have chosen to use some of their wealth to landscape their campuses in oaks. You might then imagine the campuses as, well, trees, their roots breaking up the surrounding concrete and spreading ecological function. But you could just as easily see the direction reversed, all the resources and energy flowing through the roots into these leafy green campuses where high-paid workers surrounded by expensive oak woodlands create ever-more lavish virtual worlds, even as the sprawling concrete-and-generic-tree landscape around them falls further behind.

Near the end of my walk I turned a corner at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View. The museum bills itself as the recorder of Silicon Valley’s legacy. It advertises a 25,000-square-foot exhibit called Revolution: The First 2,000 Years of Computing. Its volunteers restored and maintain a working 1960s-era IBM 1620 computer. A new exhibit celebrates the vivid imaginative landscapes of World of Warcraft.

Outside, the museum is landscaped with London plane trees.