When I started the Ph.D. program in Environmental Science, Policy & Management at UC Berkeley 12 years ago, I knew two things for sure: I loved islands, and I loved insects. But I was in love with the wrong things.

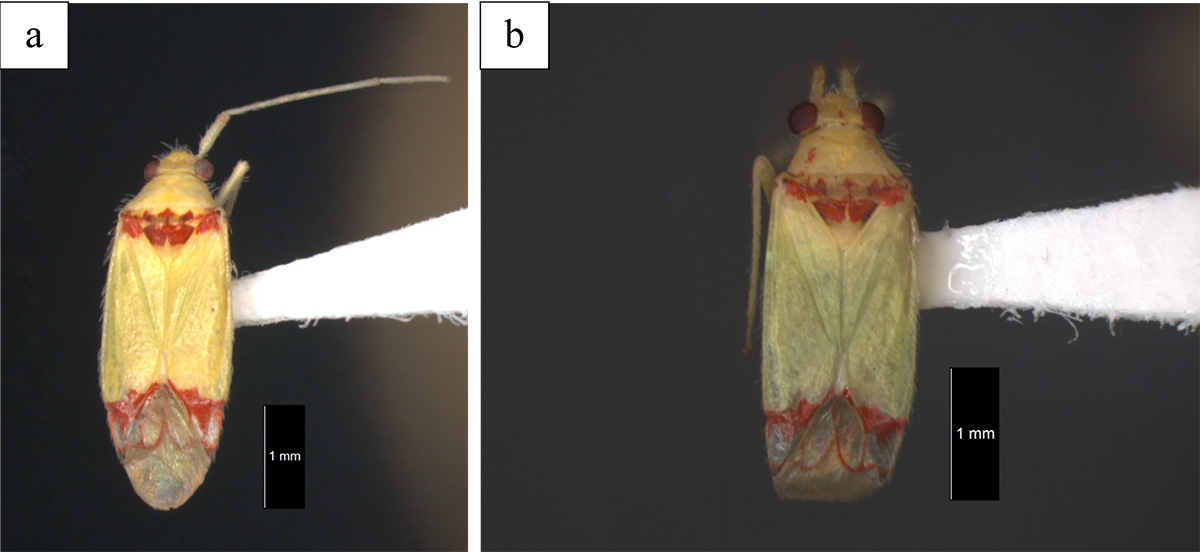

To make it in the rarefied atmosphere of research academia, I had to be driven by mechanistic questions, not places or organisms. A passion for the beautiful colors of butterflies or the verdant landscape of a tropical forest is quaint and nice and all, but in the eyes of my professor mentors, the gatekeepers of funding and peer review, a line of inquiry based on the “what” or “where” versus the “why” was just not rigorous enough. In my case, I had read a line in a government report about some unusual looking insects in the remote Austral Islands of French Polynesia and how they appeared to represent “undescribed species,” and I knew right then that my dissertation would be about discovering and describing them. I rushed into my advisor’s office (a wonderful person, by the way) to announce the good news, and was met with a befuddled look.

“That’s great, Brad, but what is your question?” she said.

“Um, what are these bugs?” I replied, adding extra intonation at the end of the sentence to emphasize that I was indeed addressing a question in my research.

But it just wasn’t the right type of question; it was too descriptive. A Ph.D. should be about higher-order thinking, like asking the question what causes new species to form? rather than what are these species?

I was heartbroken—I had paid my dues as an undergrad, slogging through all those calculus classes and other pre-requisites so I could fully indulge my inveterate passion for invertebrates. And now I was being patted on the head and essentially told I would make an excellent graduate student in 1860.

I think many biology academics have done a great disservice to the broader impact of our field by approaching research in this way. We have only described an estimated 15 percent of the species on our planet, and yet the study of species documentation, taxonomy, is derided as being too old-fashioned to deserve funding (natural history is similarly dismissed). If the point of basic scientific research is to advance knowledge for society’s greater good, why aren’t we listening to what society wants to know? The general public wants to learn about the natural world because it is intrinsically fascinating; that instinct that E.O. Wilson called “biophilia” is what keeps zoos, aquariums, and natural history museums immensely popular attractions around the world. Life is cool for its own sake.

I realized that I had to play the game to get through my Ph.D. “What are these bugs?” became “The relative role of geography and ecology in the radiation of Pseudoloxops (Hemiptera: Miridae) in French Polynesia” in my thesis—but for the next seven years I quietly plotted my next move—I would zig where everyone else zags. I had discovered the joy of teaching, and decided that I would put those skills to use in a very different academic environment, one more closely aligned with society’s wants and needs: community college.

Community colleges prepare students directly for the workforce, and as I thawed from the carbonite of grad school, I realized how many non-academic natural history job opportunities exist in the Bay Area, from government agencies (East Bay Regional Parks District and EBMUD, to name two) to environmental consulting firms to non-profit organizations. While the research universities turn their backs on the traditional “-ology” classes (herpetology, ornithology, etc.), we in the community colleges have a unique opportunity to double down on them. It’s nice to know signatures of population structure in the genome of the acorn woodpecker, but what good is it if you don’t know what an acorn woodpecker is?

And so I set out to build the new Natural History & Sustainability program at Merritt College, one of Oakland’s two community colleges (Laney College is the other). The goal of the program is to train college kids for careers in nature, providing a solid foundation in geology, environmental science, and those “-ology” courses shunned by research academics. We are developing Certificates of Achievement (a credential emphasizing specific job skills) in the areas of Conservation & Resource Management, Urban Agroecology, and Natural History & Resources to address job needs.

So besides training, why else start a natural history program in 2018? On the first day of my introductory natural history class, I ask my students to walk around the classroom writing on the world’s largest Post-Its answering the question: “Why is nature important?” Several write things they think I want to hear, things that are true but banal: “To know where we came from;” “so we can plan for the future.” But what I rarely see is arguably the most important answer: “Because it’s good for me.” More and more research is demonstrating how time spent in nature, even as little as twenty minutes, improves our health by changing our physiology: cortisol levels (a stress hormone) drop; heart rate decreases; attitudes soften. Some of this best research is happening right here at home—Dr. Nooshin Razani of UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in Oakland’s SHINE (Stay Healthy In Nature Everyday) program provides prescriptions and transportation for low-income families to visit nearby parks, and has documented the health benefits. So to corrupt the old Wall Street Gordon Gekko quote: “Green is good.”

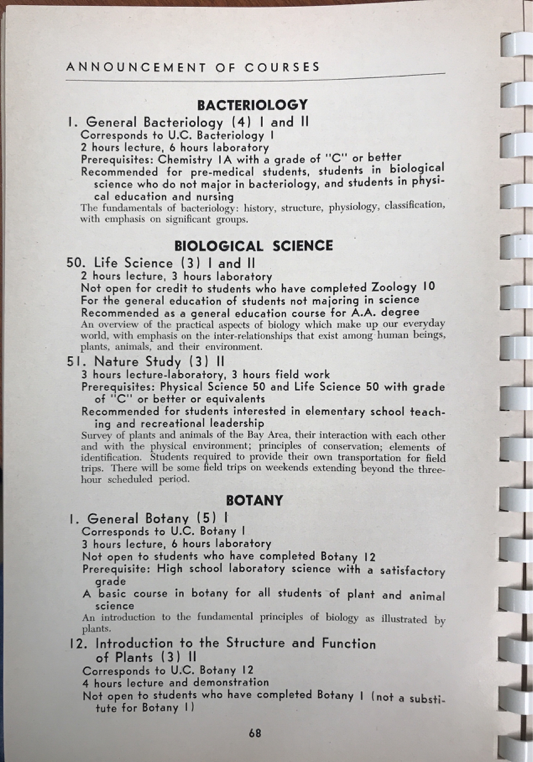

Merritt College has a long and proud tradition of environmental science and natural history dating back to the late 1950s and the seeds of the environmental movement—a recent deep dive into the library archives revealed this gem from the pages of the 1959-60 catalog, our first natural history course with the charmingly antiquated title “Nature Study.”

When launching our new program, the decision to keep “Natural History” in the title was purposeful. Some feel that the term conjures images of moths and mothballs, too old-fashioned to keep up with what they say is the desultory attention span of today’s youth. But it was essential to me that it stay. People get thrown by the word “history,” thinking that it refers to nature in the past tense. But the term is borrowed from the Latin historia naturalis, meaning “inquiry into nature.” And so “natural history” is the perfect term to encapsulate a program dedicated to an exploration of all aspects of nature.

Once the name was down (we added “sustainability” to reflect the program’s commitment to a renewable future), we turned to our logo. While an iconic native plant or mammal may have been the obvious choice, we chose a lichen to be our poster organism for two reasons that reflect our mission. A lichen, a symbiotic organism consisting of a fungus, alga, and (sometimes) bacterium living together, represents the interdisciplinary nature of our program, with classes in the departments of Biology, Business, Environmental Management, Geology, Landscape Horticulture, and Native American Studies. The lichen is also an understudied and underappreciated organism, symbolizing the people of color who are underrepresented in the environmental sciences. Social justice is central to our mission, and Merritt College, where 79 percent of students are people of color, is the ideal place to grow the program.

Merritt has a particularly proud history in the African-American community, being the alma mater of Black Panther founders Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale and the site of the country’s first African-American Studies program. Unfortunately, the black community was not historically embraced by the environmental movement, one of the many reasons for why African-American participation in nature is so low. As scholar Carolyn Finney describes in her book Black Faces, White Spaces, even John Muir expressed racist attitudes in his writings, a fact few are aware of: “On his ‘Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf’ in 1867, through lands that had been devastated by war, he spoke of Negroes as largely lazy and easy-going and unable to pick as much cotton as a white man,” Finney writes.

I could teach my introductory natural history class without veering into the uncomfortable waters of environmental racism. I admit that when I first designed the course, I didn’t give a lot of thought to discussing race—what does the color of your skin have to do with learning about frogs or snails? But I was wrong. When a black person flips through a magazine and almost all of the ads set in nature feature white people (as documented in peer-reviewed research), what does that do to their sub-conscious? When a young person of color goes on a guided hike for the first time and none of the park rangers look like them, are they likely to follow that career path? As Finney told my class in a guest lecture last spring, racism is not just about explicit epithets, it’s about power, and minorities by and large do not feel empowered in the outdoor world.

I ask my students why they think people of color are not more involved in nature with activities like hiking (a 2011 study in national parks, for example, found that only 2.06% of park visitors reported their ethnicity as black despite comprising 14% of the U.S. population).

“In my opinion the percentage of people of color going hiking is low because they don’t have time,” one student wrote. “Most people of color spend most of their time working to get money as they didn’t grow up in a wealthy family so they have to work for it so there’s no time for hiking.”

“Hiking is for white people,” wrote another.

We have a lot of work to do.

When I started at Merritt, I also began to understand a more authentic version of diversity than the buzzword often thrown around university campuses. Beyond the straight-forward statistics of race and ethnicity, I encountered true diversity in the area of privilege, class, and life experience. I finally came to understand how lucky I am. In my first semester, one of my students missed a mid-term exam. Thinking he had just blown it off, I came to the next class ready to deliver a harsh reprimanding. I asked him what happened.

“My sister got shot,” he said. “I’ve been in the hospital ever since.”

And yet only a couple of days after losing a sibling to horrific violence, this student was in my class, ready to learn.

We’re a small college that struggles to hire enough staff. It’s an adjustment from the rarified air of “the relative role of geography and ecology in the radiation of Pseudoloxops.” But I love it. I finally get to work in an environment where my passion for nature is not only enough, it’s contagious.

Because as local environmentalist and Outdoor Afro founder Rue Mapp puts it: “Nature is a generous teacher; it’s there for all of us.”