By the time I got out of my car at the Petaluma headquarters of Point Blue Conservation Science on the morning of November 8, the sky had already turned a sickly yellowish tan. On the drive up from Berkeley, I had started noticing what first appeared to be yellow fog to the northeast, while the sky remained clear and blue to the west. Strange, I thought; fog usually comes in from the west. By the time I reached Petaluma, the whole sky was blanketed by the sickly yellow haze; the acrid smell when I got out of the car told me immediately this was not fog. Inside the office, Ellie Cohen, CEO of Point Blue, was already communicating with Point Blue field staff about the fast-moving wildfire that had ignited just a few hours earlier near the town of Paradise in Butte County. “Get inside and be safe,” she pleaded. What we couldn’t have known at that point was that this was the start of the deadliest wildfire in California history, leaving 86 people dead and thousands displaced.

This was an all-too-appropriate segue to my interview with Ellie Cohen, on the occasion of her impending departure from Point Blue Conservation Science (founded in 1965 as Point Reyes Bird Observatory/PRBO). Because if the world at large had been heeding Ellie for the past 12 years, we might already be on track to make the choices and changes necessary to avoid this apocalyptic, smoke-filled vision of the future of California … and the planet.

Despite the grim message she has been delivering about climate change, Ellie’s just not a downer type. She has an upbeat way of engaging her audience – whether it’s an audience of one or one hundred that disarms you for the powerful message she is about to deliver. And that says you don’t have to be discouraged, at least not yet, while there’s still so much we can do—and should do—to make the world a better place.

I’ve been fortunate to know Ellie for most of her two decades at the helm of PRBO/Point Blue, a tenure that more or less coincided with my years working at Bay Nature. I can’t possibly count the number of times I called on her for advice on everything from fundraising to climate change. Despite the fact that she was an influential, overextended, and constantly-in-demand CEO of a growing and well-respected conservation organization, she never failed to respond to those queries. Now that she was on the verge of leaving the organization she had built into such a major force in both the local and global conservation arenas, I was eager to hear her reflections on 20 consequential years.

After shutting off her computer, Ellie leads me into a small conference room where we spent the next 90 minutes tracing her career, leading up to her decision to relinquish the reins of Point Blue at the end of this year.

“I couldn’t just study butterflies, it was too esoteric. I needed to do something that would more directly impact people’s lives.”

Where did this journey start for Ellie Cohen?

Ellie grew up in a racially diverse part of Baltimore, with politically and culturally active parents who took her and her siblings to civil rights protests, anti-war demonstrations, and Broadway musicals. But visits to the woods or the beach were rare. “No one mentored my love of nature; no one took me camping or birding,” she says. So it wasn’t until college at Duke, where Ellie majored in botany, that she really began to explore the natural world: “I took every field class I could, and loved it!” Her interests turned to entomology, and she first came to California as an intern for a study on Edith’s checkerspot butterflies.

After graduating in 1978, she was accepted into grad school at UC Davis to study butterfly ecology under eminent entomologist Art Shapiro. But then came the traumatic nuclear disaster at Three Mile Island, and the political side of Ellie’s background kicked in, hard. “I couldn’t just study butterflies, it was too esoteric,” she says. “I needed to do something that would more directly impact people’s lives.”

So she left butterflies behind to help build a coalition to oppose nuclear weapons and nuclear power in Orange County—“behind the Orange Curtain”— where a lot of defense contractors were based. (No one has ever accused Ellie of taking the easy road!) As part of her education as a political organizer, she was trained by Fred Ross Sr., a veteran activist who had developed the successful house meeting strategy for Cesar Chavez and the United Farmworkers to win recognition of their rights. This direct person-to-person style of organizing is clearly part of Ellie’s persona, and has been one key to her effectiveness in other arenas, including fundraising and public education.

For most of the 1980s, Ellie worked as a political organizer for different organizations in the anti-nuclear and anti-intervention movements, including as National Field Director for Neighbor to Neighbor doing grassroots organizing to pressure Congress to cut off military aid to the right-wing Contras in Nicaragua. At the same time she enrolled in the graduate program for public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. “Combining work and school, and commuting between Cambridge and targeted swing districts across the country, made this one of the busiest period of my life,” she recalls, “but I was fully engaged and achieved more than I ever thought possible. And it was fun! And by that spring [of 1989], Congress defeated aid to the Contras. It made me believe in democracy again!” (I apologize for the excess of exclamation points, but that’s the way Ellie talks!)

After the successful conclusion of that campaign, Ellie yearned to return to California, and a year later she was back in the Bay Area, working with groups that ran campaigns and did fundraising for unions, Democrats and progressive nonprofits. But after seven busy years in those trenches, she decided it was time to step back and re-focus. “I was trying to figure out what to do next, asking myself what is it I truly love? And I decided it was the combination of ecology and helping to make a difference for our collective future.”

“There’s a shared understanding now that we’re a conservation science institution. We do research, but it’s applied research. Our mission is to conserve ecosystems through science and partnerships.”

Taking Over at PRBO

Ellie doesn’t believe in fate, so it must have been just a coincidence that at the same time, in 1998, Point Reyes Bird Observatory was looking for a new executive director. I spoke recently with Jack Ladd, a retired Bay Area magazine consultant who was then chair of the PRBO board and a member of the hiring committee. As he tells it, “There were 33 applicants for the position. Thirty-two of them were natural scientists with PhDs. And then there was Ellie.”

He knew as soon as he interviewed her that she was the right person for the job, the person who could build the organization to support the work of the scientists. As Ellie explained, “Because I had been an executive director before in a nonprofit setting, and because I had done fundraising, it turned out to be a great fit. I didn’t want to be a scientist myself, but to this day, I love learning from scientists. I told them I would be an active advocate for our scientific findings and make sure they didn’t just sit on a bookshelf gathering dust. That they would be used to make a difference.”

Ellie’s first charge from the board was to “make the organization more functional, capable of scaling up its effectiveness.” Back then, PRBO was a collection of scruffy, bird-loving, fieldwork-oriented scientists doing great work, but each in his or her own silo. Ellie’s first challenge was to break down those silos and instill a common, shared sense of purpose. “It was a cultural shift for the organization, but we got there,” she says. “There’s a shared understanding now that we’re a conservation science institution. We do research, but it’s applied research. Our mission is to conserve ecosystems through science and partnerships.”

When Ellie came on board in 1999, PRBO was living hand-to-mouth on a budget of about $2 million, operating out of a run-down farmhouse near the edge of Bolinas Lagoon, leased on the cheap from Audubon Canyon Ranch. Its only asset was the Palomarin Field Station, site of the longest-running dataset of bird populations on the West Coast. Valuable in theory, but essentially worthless as a liquid asset, since it’s on national park land and as such could never be sold.

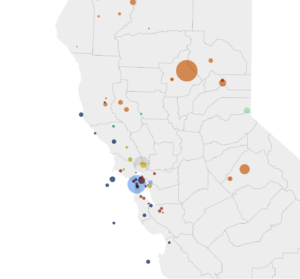

The rustic, edge-of-the-continent locale was definitely part of PRBO’s identity and self-image. But there were problems. First of all, as West Marin became ever more expensive, it became harder for staff people to find housing nearby. Secondly, as PRBO expanded its work on bird populations and their habitats into San Francisco Bay, the Central Valley, the Sierra Nevada, and the California Current, the commuting challenges became even greater. And as staff grew beyond 30 people, there was no place to put everybody. Finally, as PRBO became more of a hub for the collection, maintenance, analysis, interpretation and distribution of scientific data, it became harder to tolerate the outage-prone electrical service and poor internet connections at the Stinson Beach site. So in 2003, Ellie and the board began a search for a new home for the growing organization.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

For the full list of Point Blue’s collaborative accomplishments under Ellie Cohen, click here.

Who would have expected this organization housed in a funky old farmhouse on Bolinas Lagoon to wind up in a gleaming new office park in south Petaluma. But the site was right next to a bird-friendly wetlands (Shollenberger Park) and conveniently located just five minutes from the 101 freeway. A wildly successful capital campaign in 2004-08, overseen by Ellie, raised over $9 million, and allowed the organization to take over two-thirds of the new building: 20,000 square feet of modern, high-speed-internet-enabled office space overlooking the marsh, with its trails and shorebirds. It also established PRBO’s first reserve fund of $3 million. Ellie is clearly proud of the transition that the building and reserve represented for the organization.“It was hard to leave West Marin, because it was so much of our identity. But we realized that we needed to spread our wings. Having this new headquarters was an amazing step forward. It gave us an accessible hub and has become a reflection of the solidity of the organization and the excellence of our work.”

Another step in the evolution of the organization that Ellie oversaw was the name change from Point Reyes Bird Observatory to Point Blue Conservation Science in 2013. Ellie says this was actually the hardest thing she had to do in her time as CEO, because it crystallized the changing culture of the organization, and there was such a strong emotional attachment to the old name and the community it represented. But, she says, “The old name didn’t capture the cutting edge work we were doing, nor the geography we were working in, nor the biology.” With all the work on San Francisco Bay, on range management in the Central Valley, on watershed restoration projects in the North Bay, and expanded coastal and ocean research, the organization was doing so much more than observing birds in West Marin. In hindsight, Ellie says, she wishes she had done more consultation with outside stakeholders on the change. “But name changes are like paint colors – it’s really hard to find the right one. But we had to make a change.”

“It wouldn’t be enough to look at the habitats and life cycles of these bird species. We would have to look at overall ecosystem function in the context of the entire biosphere. Climate change would be the thing we had to address in all our work.”

The New Challenge: Taking On Climate Change

In 2005-06, about the same time the organization was moving its headquarters, PRBO scientists started reporting some troubling anomalies out at the Farallon Islands, where the organization had been staffing a research station and collecting data since 1968 in partnership with the US Fish and Wildlife Service. During those two years, there was a complete breeding failure for the islands’ population of Cassin’s auklets, a small pelagic fish-eating bird that nests on the island. “In March 2005, all the signals were ripe for a good breeding season, and the birds were there, laying eggs,” she says. “But then the krill were just gone. In 2006 it happened again. A number of us were convinced this was due to climate change, but you couldn’t say for sure, because there was no precedent for it. It turns out that instead of the normal upwelling, the ocean currents had changed. For me, this was a huge wake-up call.”

Ellie is not the kind of person to ignore wake-up calls, or to leave them to others to pick up. She notes that this was the year of An Inconvenient Truth and a growing public awareness that “global warming” wasn’t some issue about the distant future. She recalls, “At PRBO, we had dealt with climate change on an individual issue basis, but for the first time we started to look at it organization-wide, and we realized that there were things happening now that were indicating significant environmental change, and that looked like what scientists were predicting for a climate-changed future. So I realized that for us to stay relevant, we would have to adopt new approaches to our work. It wouldn’t be enough to look at the habitats and life cycles of these bird species. We would have to look at overall ecosystem function in the context of the entire biosphere. Climate change would be the thing we had to address in all our work.”

In January 2007, Ellie enrolled in Al Gore’s second national training for climate change communicators. In return for the training and a copy of the slides from An Inconvenient Truth, trainees had to commit to making 10 presentations over the next year. Ellie took that ball and ran with it, doing 26 presentations that year (and dozens more thereafter). She incorporated slides about the changes at the Farallones and in the ocean currents to highlight climate change impacts on natural systems, something missing from the original slide show. As Ellie explains, “My main message was, ‘Wherever we live on the planet—whether it’s in the middle of the Amazon or in the middle of New York City—we’re all dependent on nature to survive, so we need to be able to ensure that nature will survive.’ If we don’t look at protecting ecosystem services – the benefits to human beings from nature – if we don’t do that, then we’re goners.”

In 2008, Ellie was able to convince a major donor (no foundation would touch it back then, she says) to fund a seminal project to model the impact of climate change on San Francisco Bay’s tidal wetlands. Given the tremendous progress made in this area since, it’s hard to remember that just a decade ago, there was no hard data with which to address the threat of sea level rise on tidal wetlands. This study became a key component of “Our Coast, Our Future”—a collaborative project of Point Blue, the U.S. Geologic Survey and others —which developed the model now being widely used to design sea level rise adaptation projects for the entire California shoreline.

In order to promote more of this type of regional approach to challenges to the Bay Area’s natural systems, Ellie worked with Maria Brown of NOAA and Mendel Stewart of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to launch the Bay Area Ecosystem Climate Change Consortium. The purpose was “to bring together scientists and managers and policy makers—people who had never sat down at the same table together—to understand climate change impacts on natural resources and how to prepare for it.” Ellie says she’s particularly proud of BAECCC’s success in “putting the issue of climate change front and center on the Bay Area’s conservation agenda and promoting nature-based solutions to climate change adaptation. We really influenced the conservation community to think about climate change. There were people who didn’t want to, who pushed back. But there‘s been a huge shift in the last few years, when everyone in the conservation community, everybody who manages landscapes and seascapes, has come on board.”

In recognition of Point Blue’s leading role in the climate change arena, in 2017 the organization was selected to be an official non-governmental organization (NGO) observer of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). One of Ellie’s last official duties as CEO of Point Blue was representing the organization at the December 2018 conference of the UN Convention in Katowice, Poland. Ellie reported from the conference that she was encouraged to see that many other countries are embracing the concept of “nature-based solutions as an essential part of the way forward to a safe and stable climate.”

“So after 20 years, I guess I need a little time off the clock, a little time where I don’t have to follow all the rules. Where I can let go and spend more time outdoors.”

What’s Next?

It is hard to imagine that Ellie is going to actually leave this, her chosen field of battle over the past decade, when she steps down as CEO at the end of 2018. So I ask her what might be next.

She prefaces her answer with a family story. “A few years ago, I was driving my son to school when he was in the first grade and, out of the blue, he says, ‘I know what I want to be when I grow up; I want to be a boss.’ I burst out laughing and told him, ‘You know, being a boss is really hard. You have to follow all the rules, even more than everybody else. You have to set an example and you’re never off the clock.’ So after 20 years, I guess I need a little time off the clock, a little time where I don’t have to follow all the rules. Where I can let go and spend more time outdoors.” Along the way, Ellie says she’ll take time to figure out what her next “Help save the planet’s future” job will be. “I have one more major thing to contribute to life on this planet and I’m excited to see what it might be.”

So are we, Ellie; so are we.