Imagine yourself a woman sitting on a barstool. “Last call!” the bartender shouts. Lights come up awhile later and the activity of the males picks up: some you’ve avoided all night, a few you smile at, some just won’t take a hint as they circle back for one last try. Now, imagine there is no roof on this bar, that you are actually sitting on the ground and the ground is at the top of a hill or mountain. Now finally imagine … you are a female butterfly.

Ladies and Gentlemen, the rules of courtship are not all that dissimilar between humans who go in for the bar scene and butterflies. Unlike humans who have many options as to how to live their lives, the purpose of the butterfly adult phase is reproduction. (Adult butterflies are also called “imago” — a word I’m determined to bring back: ova, larva, pupa and imago. It’s all butterfly, but somehow this phase got labeled ‘butterfly.” The plural — imagines. How cool is that?)

Imago is the stage we all seem to be fixated on. Why? Simple. Because they are beautiful, mesmerizing in flight and hypnotic to us at a rested, pulsating stance. But if you see a butterfly the way you think of butterflies, wings and color and flight, remember this is just the sex phase, folks: the find-a-mate-lay-some-eggs-and-die phase. Sex and the Single Butterfly is not for the faint at heart. It can be rather savage and antiseptic. If you are brave and willing to dial back your own anthropomorphism, I’m going to walk you through this secret world.

O.K. We’ve wheeled out the bar set and you are now that female on a summit. How did you get there? Well, after you eclosed (another cool Scrabble word: eclose — to emerge from the pupa or chrysalis or cocoon) a great deal of you execute the involuntary response of traveling upward to higher ground, one of the little developments evolution has given you to find other butterflies. Studies have shown that there are more males than females at a hilltop, on average a ratio of 20 guys for every girl. In the Bay Area, one can observe this primarily with mournful duskywings (E. tristis), all three of our Painted Ladies: the American lady (Vanessa virginiensis), the painted lady (V. cardui) and the West Coast lady (V. annabella). Both anise and pale swallowtails (Papilio zelicaon and P. eurymedon) are strong hill-toppers. Hilltopping is one of my favorite things to point out to folks on a walk. An apex, slam dance that always pleases the crowd.

For the non-hill-toppers, butterfly sex breaks down into two distinct behaviors: perching and patrolling. Males find a path or shoulder-height perch to wait for a gal to fly by. Examples of perching species: Lorquin’s admiral (Limentis lorquini), common buckeyes (Junonia coenia) and red admiral (Vanessa atalanta). What initially gets them going? Any type of motion. Remember, with a lifespan in general of a little more than two weeks as the imago, anything that moves might be the opposite sex. I’ve seen buckeyes dart up to hummingbirds, dragonflies. Once I watched a California tortoiseshell (Nymphalis california) go after a falling Bristlecone pinecone up in the high White Mountains of California.

A strategical tossed rock above them on a path can suss out this anticipatory behavior, before the males float back to their initial launch spot somewhat defeated.

A great example of the other behavior — patrolling — can be found in the western tiger swallowtail (Papilio rutulus) soaring above the heads of people in downtown San Francisco. Males follow pheromone trails left by the girls up in the canopy of the London plane trees that line both sides of Market Street. A friend of mine once said she disliked the term patrolling as it connoted “male domination.”

Unfortunately a great deal of butterfly courtship looks like sexual harassment from our vantage point. I once heard a rather violent bang above my head while standing in a meadow. It was a male monarch (Danaus plexippus), for lack of better words, “attacking” a female mid-air, pulling her to the ground and overpowering her to mate. The noise was created by such a large butterfly smashing into another. One may not like the semantics, but this behavior of monarchs has actually been referred to as a rape.

I don’t know about you but it is the wings of butterflies that initially rocked my world and had me drink deep from the Kool-aid of this hypnotic cult. We are all hardwired for pretty and color. Turns out butterflies are as well. And like us they’re sensitive to the appearance of the opposite sex: males and females tend to look different (sexual dimorphism). That’s true of about 80 percent of our Bay Area butterflies. The other 20 percent where the sexes look the same (mourning cloaks, California tortoiseshells and satyr commas, etc.) have instead a size dimorphism — girls are bigger than boys. Why? Because they are carrying the eggs.

Butterflies also use ultraviolet light while scanning wing patterns with their compound eyes in ways we can’t even see. (Ultraviolet light was once described to me by someone as “something just a little more than … violet.”) Not sure that was helpful. Male butterflies reflect more ultraviolet than females. The bright colors of the scales on the wings of males are due to three evolutionary things: sexual selection from the female, competition from other males, and traits to dodge predators. Learn your wing patterns, my friends. It’s one of the primary factors in butterflies finding one another and it will open up the world of identification.

Once the motion and pattern are identified and it’s clear it’s the same species opposite sex before them, it’s time for the pheromone bath. They both emanate sexually-stimulating chemicals that are received in different parts of one another. Butterflies deal in close-range pheromone exchange, literally on top of one another (moths deal in long-range exchange — one of the primary differences between the two). She likes his Paco Rabanne, he likes her Chanel #5. If everything is copacetic, the two will continue on to copulation, which lasts on average about an hour for butterflies.

And now let us consider the plight of what the female Parnassian butterfly goes through.

An Old World subfamily of the swallowtails (Papilionidae), she pupates in the loose cocoon amongst the gravel and rocks. Males patrol and seem to be able to find her even when she’s still within the cocoon. I saw a photo once of a group of male Parnassians on the ground in a circle … waiting for her to eclose. She is pounced on by the most dominant fellow and mated even before her wings are dry. As a parting gift, he leaves a waxy, vaginal plug called a sphragis (literally Greek for “seal”) that prevents others mating with her. Most male butterfly spermatophores destroy the last guy’s that she mated with. With one of the few examples of a “chastity belt” in nature, this extraordinary adaptation takes care of that. One rarely sees a female Parnassian in the wild without this yellowish seal against her snow-white abdomen. The last Parnassian in the Bay Area was extirpated from Marin County in the 1950s. But one other genus we do still have — Euphydryas — the checkerspots — use this technique as well.

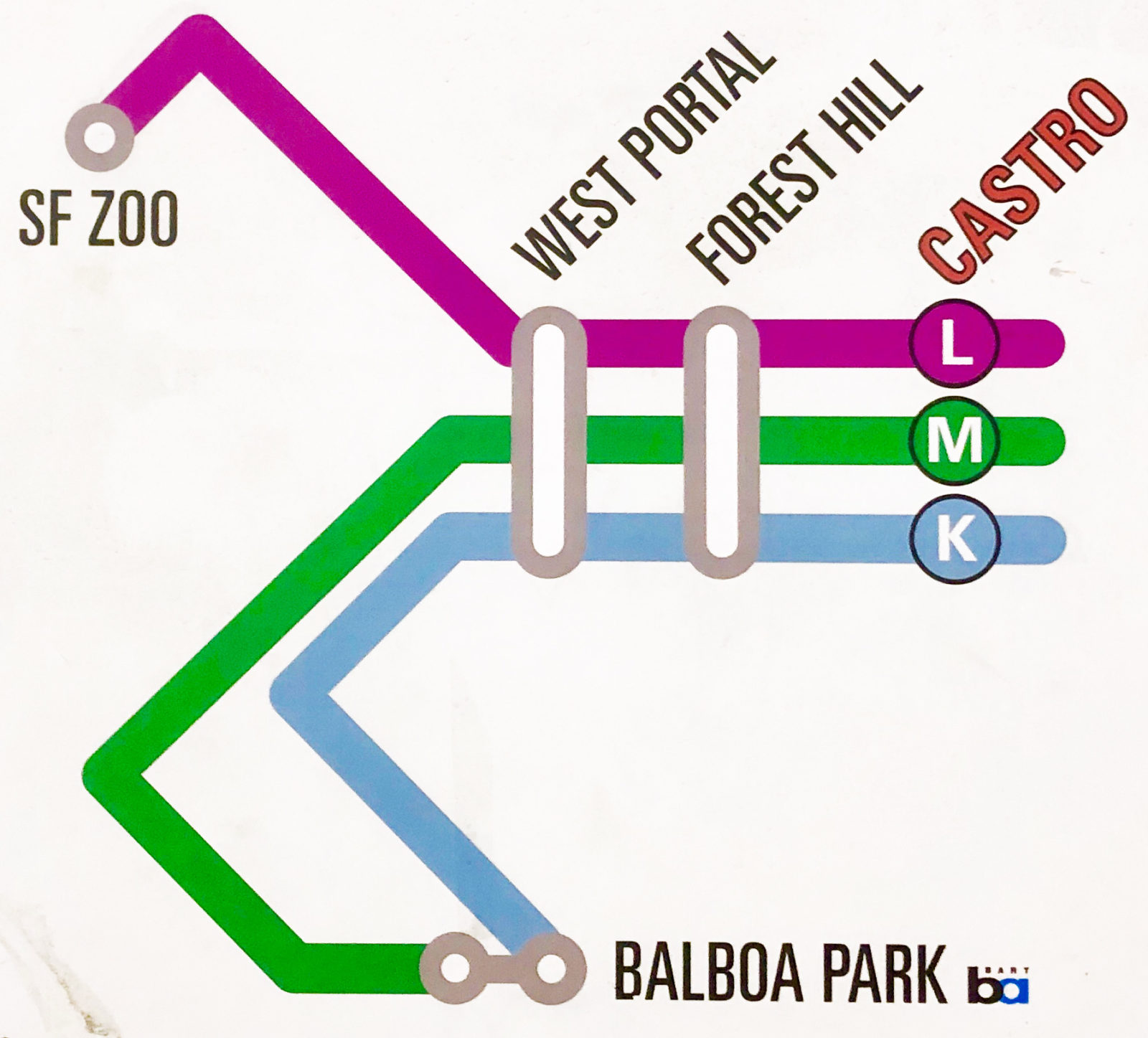

Finally, there’s a line in Art Shapiro field guide (the great Butterflies of the San Francisco Bay and Sacramento Valley Regions –– a must for all enthusiasts) that kills me every time in a good way. Once again I’m down in the bowels of the Muni train tunnels, trying not to look at something on the far platform wall. “Male external genitalia … are quite complex with all sorts of bumps, hooks, spines and such, all of which have names. A diagram of the male genitalia has been compared to a map of the S.F. Muni Metro.”

One word … ouch.