Bodega Marine Reserve research coordinator Jackie Sones has worked in or walked on the rocky shores of the North Coast almost every day for the last 15 years. But while she was surveying the reserve for sea stars in mid-June, she saw something new: strips of bleached algae draped across the rocks, like frost, and a swath of dead mussels, hundreds or maybe thousands of them, black shells agape, orange tissue shining in the sun, stretching across 500 feet of rocky tidepools.

“It’s one of the first things you see, coming down the rocks into the middle of the intertidal zone,” she said. “They were very visibly dead.”

In all her time in Bodega Bay, she wrote in her blog The Natural History of Bodega Head, she’d never seen a mussel die-off that size, or affecting so many individual mussels.

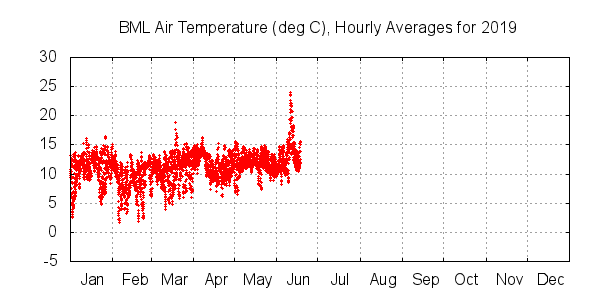

She suspected immediately that the algae had bleached and the mussels had overheated earlier in the month. While many Bay Area residents fled toward fans or movie theaters or air-conditioned libraries to escape the record-breaking early June heat wave, the mussels, which attach themselves to rocks with super-strong threads and never look back, would have just roasted in place. The air temperature in Bodega Bay on June 11 hit an unusually warm 75 degrees Fahrenheit. The normal June sea breeze disappeared. A series of mid-day low tides stranded the tidepool animals out of the water for hours while the sun beat down from high overhead.

“In the past we’ve seen patches die, but in this case it was everywhere,” Sones said. “Every part of the mussel bed I touched, there were mussels that had died.”

She went back to the lab and talked to BML marine biologist Eric Sanford, who had seen the same thing in the part of the reserve where he’d been working. The next day Sones walked a longer stretch of shoreline, covering about a quarter-mile, and still saw the same pattern of mussel death. Further reports came in of die-offs around Bodega Bay at Dillon Beach and Pinnacle Gulch, at Sea Ranch, and at Kibesillah Hill north of Fort Bragg.

Northeastern University marine ecologist Brian Helmuth, who studies the effects of air temperature on marine creatures, said that on a 75 degree Fahrenheit day, the tissues inside a marine creature glued to a rock out of the water might rise to 105 degrees. The animals try to vent the heat building up inside of them but can’t without a breeze to carry it away. The mussels’ black shells trap even more heat. “They were just literally cooking out there,” Helmuth said. “Unfortunately this was the worst possible time.”

Scientists have studied the effects of warming water on ocean creatures for decades. So-called “marine heat waves,” in which sea surface temperatures rise well above normal as happens in an El Niño, have been linked to die-offs in kelp, seabirds, and mammals, as well as migrations and species movement. But University of British Columbia biologist Christopher Harley said it’s still quite rare to document marine plants and animals dying from hot air.

Harley followed a similar event in the Bodega Marine Reserve in 2004 — the year before Sones arrived — when record-breaking heat coincided with daytime low tides in March and April. Harley had deployed temperature loggers that capture the actual temperature of the surface of the tidepool rocks, and later wrote that even though the air temperature only reached 70, the rocks around the mussel bed reached 97 degrees F. Mussels, he wrote in a 2008 paper in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series, begin struggling to synthesize the proteins they need to live at about 93 degrees F.

No one had temperature loggers on the rocks for the June 2019 heat wave, however. Helmuth had been monitoring temperatures up and down the West Coast for almost a decade, and pairing that with small “biomimics” — basically, lifelike robot mussels, planted among the real ones, that allow scientists to record the temperature as an animal would actually experience it. The experiment, which was funded by the National Science Foundation, ran out of money two years ago. “We’re trying to get them out again,” Helmuth said. “We found a group in Portugal that’s making loggers at a reduced price, and we’re hoping we can scrounge together some money to get them out there.”

So while Sones documented the die-off in pictures, it’s hard to say the precise extent of it regionally, or even conclude with certainty that it was the heat that killed the mussels.

Not that there’s much else it’s likely to have been. Helmuth said a sudden loss of oxygen would kill everything, not just seaweed and mussels. Harley said Sones’s photos look just like what he saw in 2004. Other causes — rough surf, disease, predators — leave different patterns of death, he wrote in an email.

And of course, there’s the obvious clue that it was just really hot. Mussels slowly cooking to death in their own shells is what you’d predict would happen in such unusual heat, and what scientists expect we’ll see more of as the climate changes.

Typically the hottest days at the California coast occur later in the summer and into the fall, when, fortunately for tidepool animals, the lowest low tides happen early in the morning or late at night. But in the spring and early summer the low tides shift to the late morning or early afternoon. The more unusual early-season heat waves there are, the greater the chance they line up with those mid-day low tides, the harder it gets for mussels. Future die-offs could rewrite the ecology of California’s rocky shoreline, where mussels are a foundation species that hundreds of other animals depend on.

“Small changes in temperature can produce big effects,” Harley wrote, “and that helps us understand the system and apply what we learn to other habitats.”

Tidepools are laboratories for studying the future of the ocean. They get hotter, faster; they lose oxygen more completely; they acidify more quickly; and then they reset with the next tide. The animals there survive sometimes and sometimes don’t, and the nuance could mean a lot in terms of understanding what’s coming. One thing we’ve learned, Harley and Helmuth said, is that a lot of ecosystems exist really close to the edge of what they can tolerate. “The really insidious thing,” Helmuth said, “is there’s an optimal temperature where organisms do the best, and it’s really close to the temperature where they crash.”

As a result, he said, animal populations sometimes seem to be healthiest right before they disappear. For example, Helmuth said, in Maine lobsters are booming this decade following a slight increase in average ocean temperature. The lobsters already have migrated north from New York, where they’re not caught anymore. Helmuth said he expects the temperature will increase just a bit more, and suddenly the northern Gulf of Maine fishery might evaporate as the lobsters move to Canada.

“We no longer think of climate change in the future when we do this kind of forecasting work,” he said. “It’s how do you prepare for it now.”

Harley said it’ll become more critical to predict how often these heat wave die-offs will occur for aquaculture, too. Between increasing heat and shell-dissolving ocean acidification, the industry faces existential threats from climate change. “If they lose a crop once every five years, that hurts, but they stay in business,” Harley wrote. “If it starts happening once every three years, it is time to find a different career path.”