I once spit my dinner across a room. I was watching the local news in the fall of 2008, and the story showed the opening day of the new California Academy of Sciences building. My brains left my body as well when the screen showed many, many children pulling the lids off boxes, releasing monarch butterflies into the environment — careening, wafting and falling to the ground. Five hundred monarchs, to be exact, which I later learned had been purchased from a breeder near Davis.

Why such a reaction? For the last 10 years I’d been collecting data for the Xerces Society’s annual Western Thanksgiving Monarch Count to try to determine how the species Danaus plexippus overwinters, nectars and passes through the county of San Francisco in November and December. The monarch rarely reaches double-digits here, which we now suspect was a part of a larger decline. Monarchs hadn’t been seen in such numbers in the city for decades — and here the Academy had just released 500 of them. Worse, they used no tags to try and glean any scientific information from the release. All my data had to be thrown out for that season because my species enjoys using butterflies as, to quote North American Butterfly Association president Jeffrey Glassberg, “party favors for the Human Circus.”

Greater folks than myself have explored the scientific debate of the wildlife malaise in harboring and farming insects, but for me, I’m more interested in the ethical issues this presents. Imagine going to a ribbon-cutting ceremony for a new building in a park. Along with the scissors going through the silk, forty adults open boxes and release 50 squirrels. At a new school creation our species is so happy that 90 bats are released in frenzied bliss. Sounds silly, right? Sounds absurd and ridiculous. Yet for some reason, we think nothing of dumping butterflies into these events. Why? Because, quite frankly, people don’t really think of butterflies as wildlife. We think of them as … pretty objects.

As I was quoted in the Examiner newspaper after this event, “They are not creatures to be owned. We all know the joy and exultation of a butterfly in flight after a release. But, honestly, this is a perverted relationship to Nature.”

The commercial breeding of butterflies as an industry took off nationwide in the mid 1990s, targeting weddings, graduations, baptisms, birthday parties, memorials, funerals and grand openings. The largest consumer of this garish exploitation is the Susan G. Komen Foundation, which releases a butterfly for every year you’ve been cancer-free. You may flinch at the mention of such an iconic symbol here, but wrong is wrong no matter how noble the misguided cloak is.

Soon after the Academy opening I began working with environmental lawyers (pro bono, of course) from The Wild Equity Institute to draft a document to make San Francisco the first county in the nation to ban the release of commercially bred butterflies at any event. The city is known to be at the cutting edge of new thought and progressive legislature. Both the North American Butterfly Association and the Xerces Society proudly supported the idea.

In a seminal piece on this issue called “There’s No Need to Release Butterflies — They’re Already Free,” Glassberg, Paul Opler, Robert Pyle, Robert Robbins and James Tuttle wrote, “Butterflies raised by unregulated commercial interests may spread diseases and parasites to wild populations, with devastating results. Often, butterflies are released great distances from their points of origin, resulting in inappropriate genetic mixing of different populations when the same species is locally present. When it is not, a non-native species is being introduced in the area of release. At best, this confuses studies of butterfly distribution and migration; at worst, it may result in deleterious changes to the local ecology.”

They conclude, “Although this practice is understandable to naive newlyweds-to-be (what could be more beautiful than adding butterflies to the environment?) it is really a particularly long-lasting form of environmental pollution.”

The fact that butterflies are even available for sale at all suggests something about the way we … distinguish ourselves … from Nature.

The ban document was put before the San Francisco Commission on the Environment. By a unanimous decision, the commission voted in favor of the idea. It would then need the approval of the Board of Supervisors to become law. It fell to the Department of the Environment for further review and a bunch of us began cleaning up the proposal. But by then, word had gotten out that the “wacky city” of San Francisco was trying “to ban butterflies.” (I was warned by the earlier set of lawyers to expect this.) I even avoided a call from Fox News on my answering machine. The story went national as we were still trying to get the backing of a supervisor to sponsor it before the Board. Like public nudity, cat-declawing and no-toys-in-Happy-Meals, the opposition fanned the flame of the narrative of a ban-crazy city trying to pass more frivolous and silly legislation.

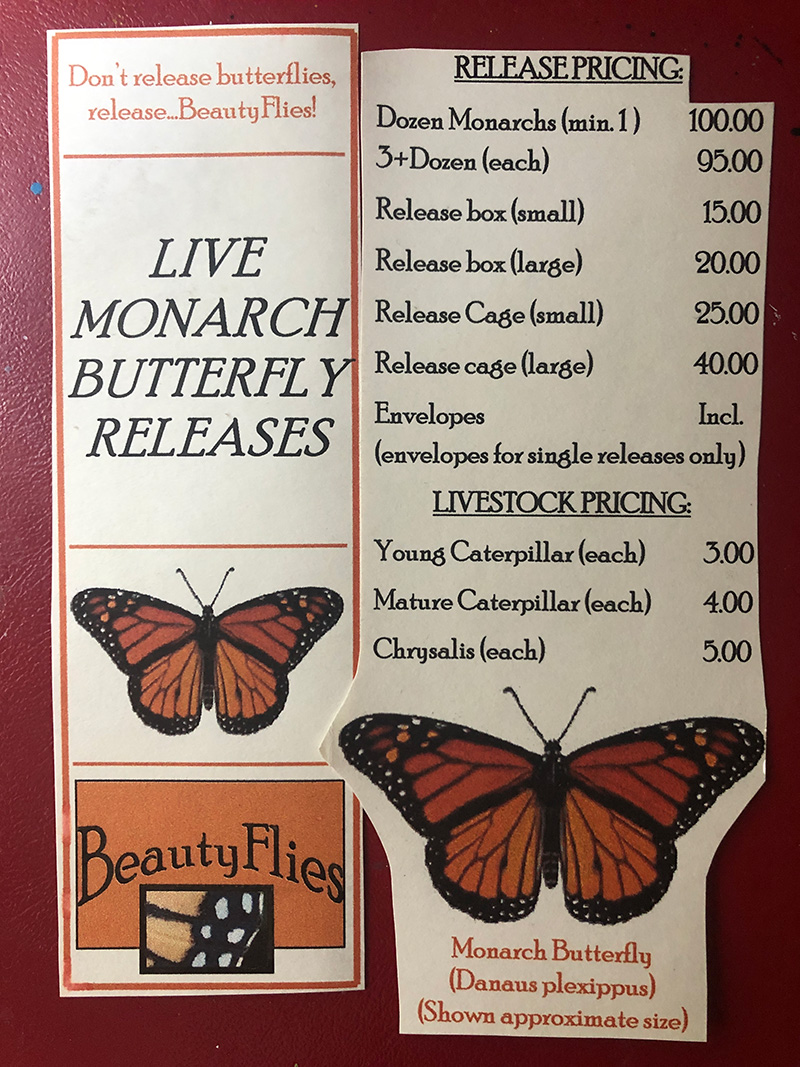

The International Butterfly Breeders Association is a 100-member strong organization. Some people who farm butterflies can make up to $250,000 a year. Peter Laufer talked to some of these folks in his brilliantly titled book, The Dangerous World of Butterflies: the Startling Subculture of Criminals, Collectors and Conservationists. Edith Smith, from a breeding farm in Florida named Shady Oaks, reads like the perfect Gramma from Central Casting. Throughout human history, the butterfly has been a symbol for transition and transformation and Ms. Smith ships them chilled to a dormant state, each protected by an individual, glycine envelope to prevent wing damage. Most requested and purchased, she tells Laufer, is the monarch, followed by the painted lady.

Smith does not recommend using a clear box to release the monarchs all at once. “The reason is that they simply do not see the glass or plastic sides and try to walk. This gives the impression of them being stressed, which is not so. It can, however, stress your guests to see them act in a way that appears as if they are trying to escape.” (I had to read that a few times … )

She is quite aware of Glassberg’s argument that captive releases might harm wild butterflies, and responds, “Notice how many times he says ‘could, might and maybe’. There is no science in what he says.”

I think for the moment we let go of the science (pro or con) of the argument and take on the ethics of the debate. Just because you like cedar waxwings doesn’t mean you have the right to raise cedar waxwings and release cedar waxwings out your back porch. The Migratory Bird Treaty of 1918, which made it unlawful to pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill or sell birds, shut down your “right” to do that. The treaty was enacted in an era when many bird species were threatened by commercial trade, primarily bird feathers. We are clearly in that era for butterflies.

My dream was ultimately cut short. Butterfly releases are now illegal in all San Francisco parks and the Presidio through our actions — a small victory. But what I couldn’t do is shut down your ability to press a button on your computer and order them from a company. That would take new law (much more difficult). It was about this time I was going through some major physical issues and I had to step away from the situation. A “Pollinators Policy” was drafted at the Department of the Environment, which umbrella-ed in much of the cause, and the butterfly-release resolution was put on hold. I feel guilty I haven’t returned to it with the glorious group of folks I was working with. That was my lesson in the politics of butterflies.

So, what can you do now? If they pass out the envelopes at your next wedding attendance with the instructions: “Open it when the bride and groom leave, you … pass it back with gentleness and say, “No thanks. I’m not comfortable with that. “

While others gasp at the contrived spectacle, you’ll have to force yourself not to enjoy it. Give the envelope back: the action is the politic. It’s a vogue, folks. Like egret feathers and shoulder pads, it will go away.

I told my 20-year-old niece about this column I was writing. “Ewwwww,” she said with that dismissive, Kardashian inflection, “People really do that? So … tacky.”

More powerful than any legislation her uncle could strive for.