For perhaps the first time in 80 years the California State Lands Commission, which negotiates and hands out leases for state-owned shoreline property, faced a decision this summer between competing ideas for the same parcel. The commission staff announced at the end of August that it will enter negotiations to lease a shoreline parcel for a park in Burlingame, potentially shaping the way the lands commission considers sea level rise in its decision-making, and the way the Bay shoreline is developed in the future.

The state owns nine vacant acres at 410 Airport Blvd. on the Burlingame shoreline just south of San Francisco Airport, and sent out a request for development proposals in May. Applications came in for a hotel, an athletic club, and an open space park. On August 27 commission staff informed the hotel and athletic club applicants that they didn’t meet the criteria for selection, leaving the park sponsors to negotiate with the staff on a lease. In either October or December, the three-member commission then will approve the lease or not on the grounds of what’s called “public trust.”

The public trust, an idea dating back to several centuries of English common law, has been defined by tradition and the courts as benefitting navigation, commerce, fishing, water recreation, or natural habitat protection. Past court decisions have ruled that housing or local services like hospitals do not benefit the entire state under public trust. In 2013 the city of Burlingame hoped to build sports fields on the site, but was told that fields serve too provincial an audience.

Hotels, because their taxes go into the state general fund and because they bring people from anywhere to the shoreline, are considered valid under the commerce and recreation part of public trust. Parking lots are considered public trust as they allow anyone in the state to access the coast. The state already leases land nearby to the waterfront Embassy Suites San Francisco Airport, the restaurant Kincaid’s, and an airport parking lot. But in rejecting the hotel proposal from the development group EKN, staff said the application wasn’t viable, according to an August 29 story in the San Mateo Daily Journal. Staff wrote that the athletic club, proposed by the San Rafael-based fitness chain VillaSport, did not meet the public trust doctrine.

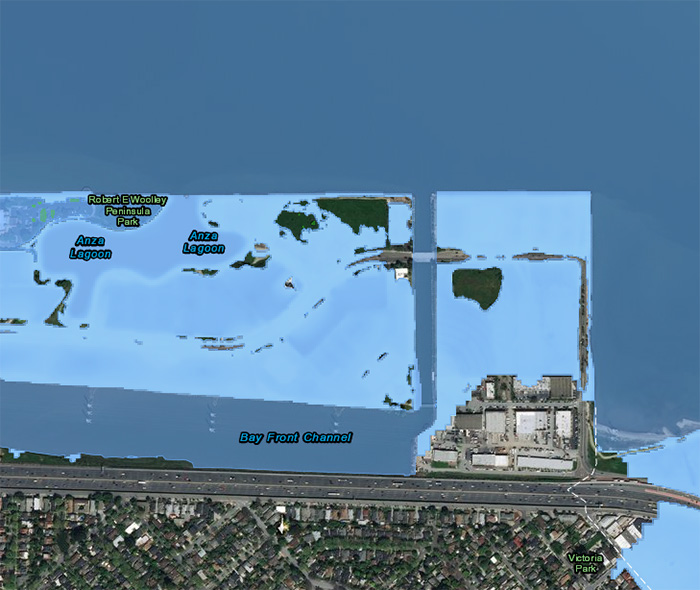

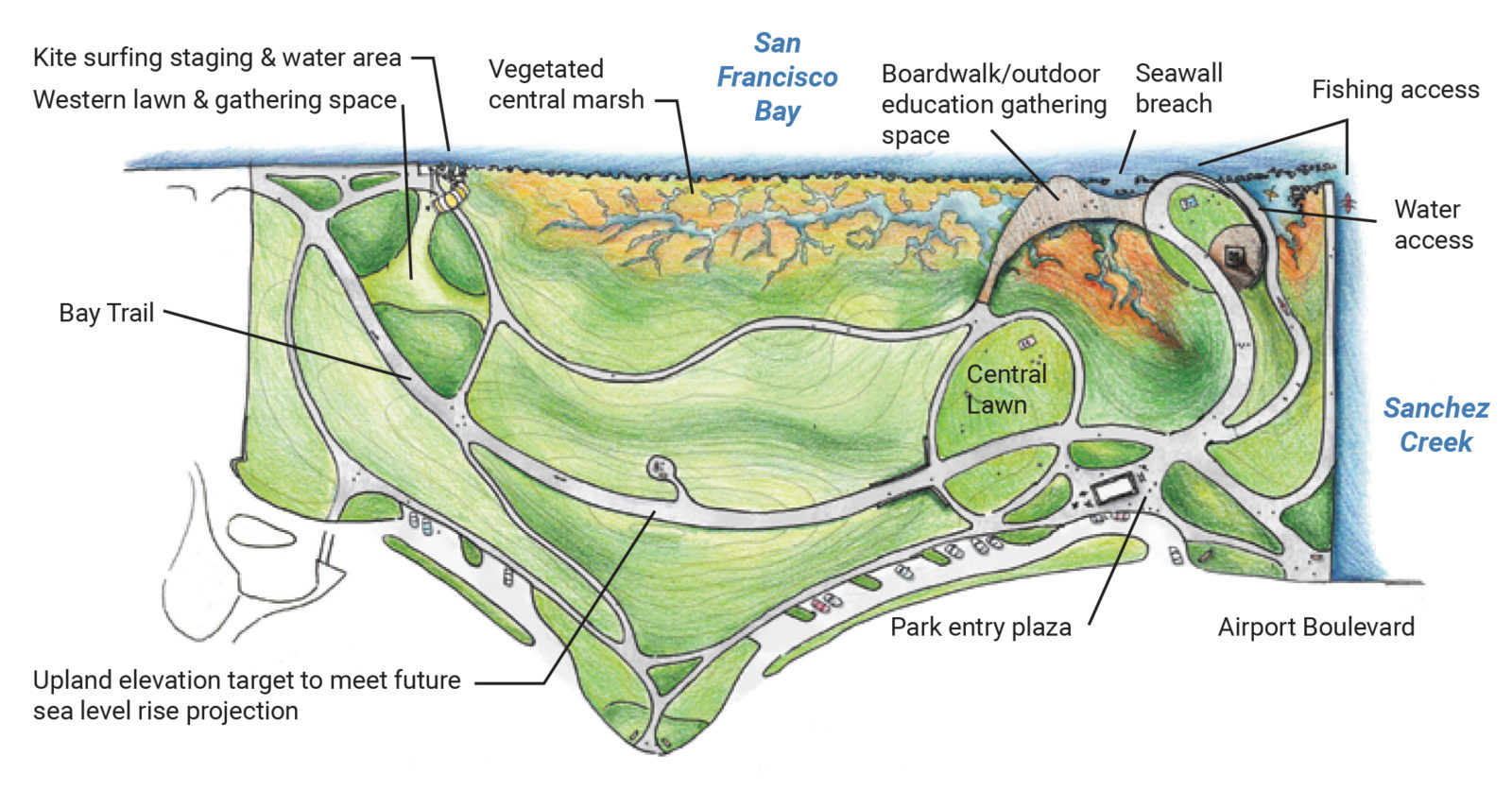

Sea level rise complicates any bayshore development, and the staff’s selection of the park to work with suggests it was a part of the calculation. The final lease could extend for up to 49 years, at the end of which the parcel could be regularly flooded by severe storms. Building on the site would eventually have necessitated a hard seawall, most likely one extended from a wall already under construction to protect the runways at SFO. The park and wetland, proposed by the neighboring government contractor SPHERE Institute and supported by a number of environmental groups, would include natural sea-level-rise protection and would preserve a gap in the seawall to allow part of the site to be flooded to create the wetland.

The commission staff sees the decision as determining how the state will evaluate sea level rise and competing proposals in the future. “This doesn’t happen very often,” said Nicholas Lavoie, the public lands manager on the State Lands Commission staff. “But we think this could come up more as it relates to sea level rise and how it affects upland uses as well.”

It’s also precedent-setting in terms of the future of the San Francisco Bay. Control of the Bay shore is divided among dozens of cities, counties, water agencies, and state and federal government agencies. But while each of those wants to make their own decisions about their own shoreline, every sea level rise project affects the rest of the Bay. Hard walls create a bathtub effect that raises the sea level elsewhere around the Bay edge, while natural shorelines and soft edges lower it everywhere. A 9-acre parcel with a quarter-mile of shoreline isn’t big enough to really affect neighboring communities one way or the other, but the question remains of whether decisions about local development, even on small sites, should or can be made with or without consideration of the regional interest. “We are de facto making a regional development decision through these local, incremental decisions,” wrote Mark Stacey, a professor of civil engineering at UC Berkeley who studies how individual shoreline projects affect the entire Bay, in an email.

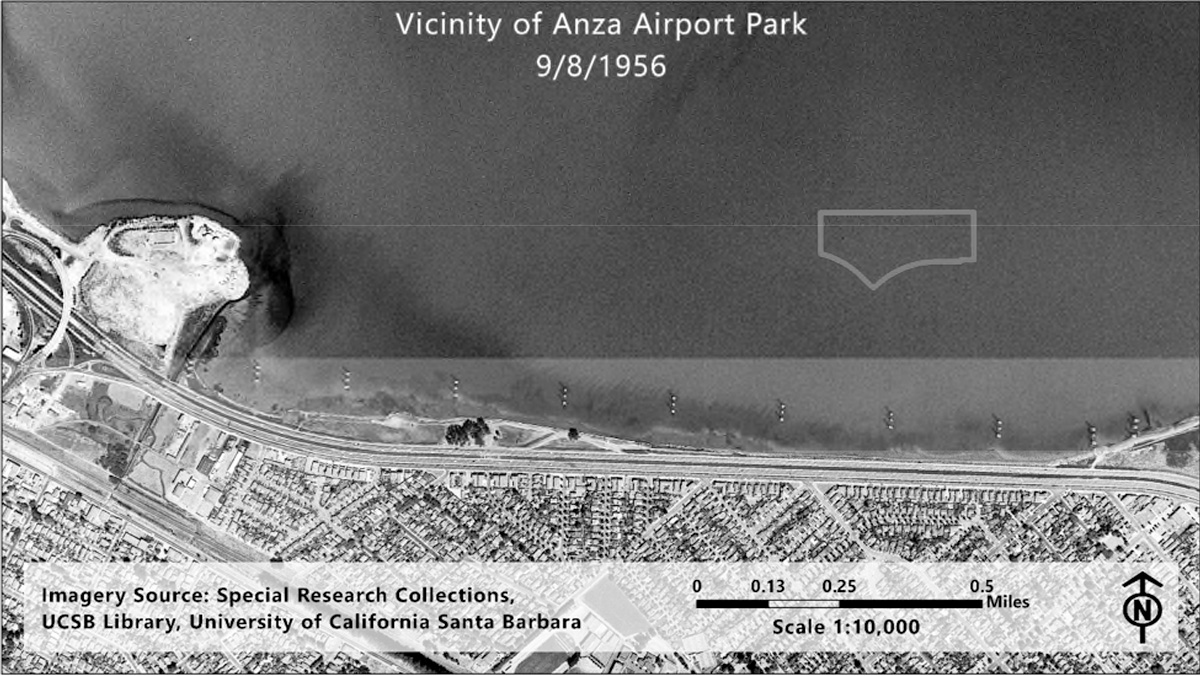

It’s unusual for the State Lands Commission to have dry land at all. As the agency in charge of shorelines and waterways, most of what the commission works on is submerged. But the Burlingame parcel took an unusual route to state ownership. In the 1960s, developer Anza-Pacific, looking to cash in with a new parking lot, filled in the open water off the Burlingame shore using rubble from the old San Mateo Bridge. The new land became the subject of lawsuits, which ended with the state negotiating a compromise — Anza-Pacific was granted leases to some of the formerly submerged land in exchange for the state taking over the rest.

And then for several decades nothing much happened at all. The parcel has never been developed. People have dumped mattresses and all sorts of trash on it. Fennel and pampas grass grew big and tall and close together. Commercial neighbors moved in, including the SPHERE Institute, a government data analytics nonprofit that owns an office building directly west of the property. In 2020 Facebook plans to open its new 800,000-square-foot Oculus campus on the property directly to the south.

In 2017 SPHERE Institute president Thomas Macrudy got a notice in the mail that a developer had applied to build a hotel on the site. SPHERE called State Lands to try to stop the hotel and recruited Bay Area environmental groups to help put together a competing proposal for a park. “There are 14 hotels within two miles,” says SPHERE Director of Business Operations Greg Boro. “When do we reach the saturation point? We think it’s reached.”

The park proposal drawn up by SPHERE and designed by ecological consultants HT Harvey calls for lawns, water access, and a half acre of new wetlands, which would help protect the upland area from sea level rise. Trails and boardwalks would crisscross the park and connect up with the Bay Trail, which runs through the property. Boro says SPHERE has covered an initial $300,000 in legal fees and property assessments, and would apply for grants to pay for an estimated $16 million construction as well as ongoing maintenance for 50 years. SPHERE has partnered with the San Mateo Resources Conservation District, which has agreed to oversee development and manage the park. The application has been championed by Committee for Green Foothills and endorsed by a variety of Bay Area nonprofit groups: Housing For All, Nuestra Casa, Outdoor Afro, Save the Bay, Baykeeper, Greenbelt Alliance, the state Sierra Club, and the San Mateo Labor Council.

“To have that alignment — labor, housing, environmental justice, it’s broad and deep support for open space,” says Helen Wolter, the San Mateo County legislative advocate for Committee for Green Foothills. “But we need to make sure that’s heard.”

CGF started a petition and sent the state 1,900 signatures in support of the park. At a “public trust needs assessment” run by the State Lands Commission, 96 percent of the public comments favored open space on the site. “As cities throughout our region rapidly build additional housing to meet the current need, we must also add adequate parks and open space to balance the increased density,” wrote Burlingame Vice-Mayor Emily Beach in an op-ed in the San Mateo Daily Journal in July. “The chance to protect this slice of the San Francisco Bay’s shoreline and create a public park in the high-priced Bay Area is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Beach says the city has allowed significant new housing growth in its general plan, which was updated in January 2019. There are recreational parks throughout the city. But in a 2019 “Shoreline Adaptation Atlas” created by the San Francisco Estuary Institute, which divided the region into watershed-level “operational landscape units,” Burlingame was part of the most-developed landscape in the Bay Area, with just 1 percent open space.

“It adds some balance,” Beach said. “That land on the Bayfront is our home for a lot of office space. It does have industrial uses, hotels. [This is] an opportunity to bring something different.”

The Burlingame City Council hasn’t taken an official position on the state’s decision, and won’t. But, in a conversation before the commission staff had announced its decision, Councilmember and 2020 State Senate candidate Michael Brownrigg said he was concerned about the opportunity cost of a wetland. With so much of the city’s funding flowing from hotels near the airport, he says it would be irresponsible to let any part of the shoreline flood before its time. “In my view, the park has one fatal problem with it,” Brownrigg said. “We on the council are charged with being fiduciaries for our city. Ultimately that land holds one-third of our city’s revenue. That land has to be protected as long as we can protect it. In a worst case scenario where all the ice caps have melted, that land is indefensible. But for now it is defensible and we need to defend it.”

The commission staff will negotiate a three-year lease with SPHERE that will give the park project time to secure long-term funding for development and maintenance. SPHERE hopes to find both through grants funded by the state’s water bond Proposition 68 and the regional parcel tax Measure AA. Once the terms of the short-term lease are established, the staff will submit the negotiated lease for approval by the three-member commission at either its October 24 meeting in the Bay Area or its December 6 meeting in Sacramento.

“While the commission will be making a decision on the short-term lease, having in mind what long-term use could be, the long-term use hasn’t been approved,” Lavoie said. “There’s still a lot to happen once a short-term lease is approved.”