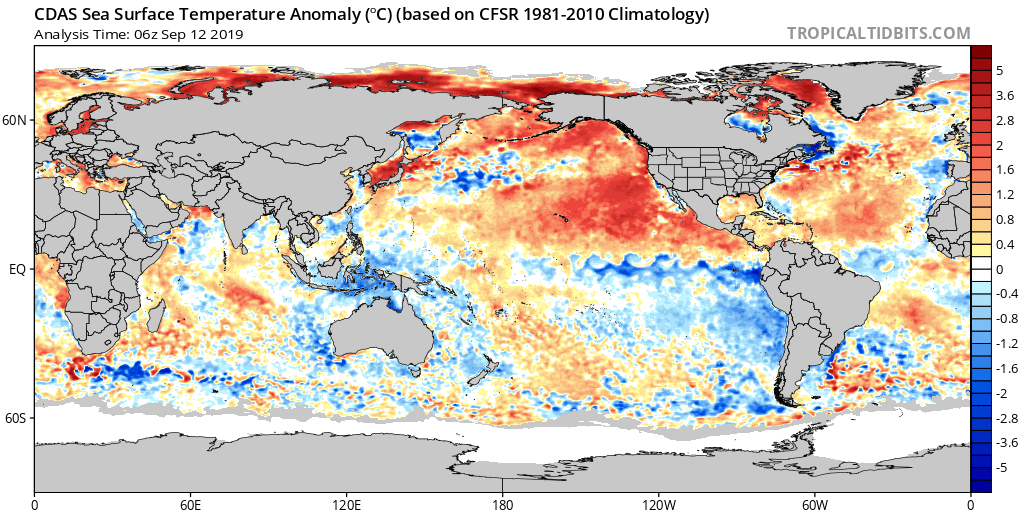

An enormous area of warm water is pooling in the Pacific Ocean off the West Coast of North America. It has reminded scientists and headline-writers alike of “The Blob,” an unprecedented area of high sea surface temperatures that spread across the North Pacific between 2013-2016 and resulted in damaging effects on ocean and human health.

But the new marine heatwave, which started spreading out from the Gulf of Alaska in June and now covers much of the Pacific Ocean, has not yet fully become The Blob 2, particularly in California. Which means the effects, too, might not be as dire as last time.

The northeastern Pacific, the triangle between Hawaii, Alaska, and Baja California, started out just on the warmish side of normal this summer — with the exception of the far north and Arctic, where exceptional warmth has been breaking records for years. Then in June, thousands of miles offshore of Washington and British Columbia, the winds that usually stir the surface and cool the ocean weakened, allowing a much warmer pool to form and start to expand toward the West Coast.

At the same time strong upwelling along the West Coast, particularly in Central California, fed a cold fountain flowing southwest for a thousand miles off the coast of Baja California. Within a few dozen miles of the California coast, it was a pretty normal, or even cool, summer. But where once that fountain might have spread cold water thousands of miles across the Pacific in every direction, this year it was a Sisyphean push against overwhelming warmth. When the upwelling slackened in August, the warm water moved in.

“Even if we have these periods where the upwelling was strong and cooled the coastal areas, that signature offshore was not as strong,” said Marisol Garcia-Reyes, a marine scientist at the Farallon Institute in Petaluma. “The moment the wind relaxes, it becomes really warm again.”

By late August and early September, as the winds weakened nearly everywhere, warm water had spread across half the ocean basin. Residents of coastal California can now feel the difference — a day or two of wind brings back the cooler water, but a day or two without it and the warm water moves in, raising temperatures on land as it nears. Since September and October typically bring weak winds and warm weather, forecasts predict a hot fall for the Bay Area.

“The warm water is virtually everywhere except in a narrow band of coastal California south of Point Arena,” said NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center supervisory research physical scientist Nate Mantua. “It’s super close to shore. You don’t have to go 1,000 miles offshore to find it — it finds you if the winds change.”

In many places offshore the water is now as much as 4 degrees Celsius above normal, said University of Washington atmospheric scientist Nick Bond, who first labeled the 2013-2015 heat wave “The Blob.” But we’re not fully back in that horror movie yet. Unlike before, the warmth this time still exists mainly at the surface, extending down about 20-30 meters. By the second and third year of The Blob in 2014 and 2015, the anomalous warmth reached as much as 100 meters deep. It’s the intensity and persistence of The Blob that separated it in the historical record, and that made it worthy of its grim nickname. For now, Bond said, the best label for this one’s still just “marine heat wave.”

“Really that heat wave (The Blob) had these huge impacts because it hung around for a couple of years,” said Mike Jacox, a research oceanographer at NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center. “It ended up extending quite deep into the ocean, and extended along the coast, while this one is still mainly offshore.”

Different parts of the ocean respond at different speeds to changing temperatures, Mantua said. Many of the most noticeable effects of The Blob — species out of place, harmful algal blooms, closure of the dungeness crab fishery, starving marine life, fall heat in coastal California — took place near the tail end of its life, or in the super-hot El Nino that followed in 2016. Mantua said he sees signatures of the current warming in chlorophyll maps of the ocean, which show extremely low production this summer outside the narrow boundaries of the California Current. Chlorophyll indicates the presence of phytoplankton, which form the base of the food chain for many marine animals.

So the big question is: will this heat wave persist? Forecast models generally say no.

The best forecast we have for winter, Jacox said, is “normalish.” “You see hurricane forecasts, they run a whole bunch of forecasts and have this cone of uncertainty,” he said. “We do something similar here, run a bunch [of models] with different evolutions of pressure systems. They show some probability of really warm anomalies, and some show some probability of things really getting cold. But the mean is just a gradual decay.”

But “you’ve got to take that with a cup of salt,” Bond said. The problem, Bond and Jacox agreed, is that the models struggled to predict the rise and even more the persistence of the last Blob. Post-mortem investigations of The Blob focused on the pattern of sea surface temperatures in the tropics, which have been linked to high pressure over the North Pacific that both weakens wind and blocks storms from reaching California. An article in the journal of the American Meteorological Society in 2017 found that a particular pattern in the tropical Western Pacific has led to warm patches in the Northeastern Pacific five times in the last six decades. It’s just that, like the 2013-2016 drought, it’s never before been this intense, or this stubborn.

“The thing that’s at least a little bit stunning for me is we’re having this conversation so soon after the last unprecedented event,” Bond said. “After that one, we said, ‘Well, we’re not going to see waters that warm for a long time,’ and we turn around and just a few years later, here we go again. That’s concerning.”

Marine scientists Tessa Hill and John Largier explain the changing ocean in “Sea of Troubles” from Bay Nature on Vimeo.

Mantua said weather patterns across the entire Northern Hemisphere seem to be getting stuck in place. This summer featured low pressure systems and cool weather for coastal California, with high pressure and intense heat in Alaska, Greenland, and Russia. Some scientists think the patterns might be linked to the unprecedented loss of sea ice in the Arctic.

“There’s something not just local to the Northern Pacific happening this summer,” Mantua said. “It could be a combination of Arctic and tropical influences that initiated it or are helping sustain it, but it’s a puzzle that hasn’t been solved yet.”

The bright side, Mantua said, is that for now the Pacific’s warm layer is shallow enough to disappear quickly. Sustained fall and winter winds would mix it with deeper water and cool everything off. It would take a while, because it takes a massive amount of energy to heat that much water by so many degrees, and now all that heat has to go somewhere. But that’s generally what just about every prediction says it will do. In a more predictable world, if we weren’t just burned by the very recent worst marine heat wave in recorded history, it might be easier to relax about the forecasts that call for the slow demise of the sequel.

“Do we have a clue where this is headed? I really don’t,” Mantua said. “I feel like it’s going to change. It’s transition season, in summer to fall the jet stream sags further south, storms come further south, the Alaska drought is starting to break, so things up there are changing seasonally and looking more ‘normal.’ I just don’t know.”