Yesterday afternoon I went for a jog along the Bay Trail and saw a bunch of little fish flipping around near the surface right at the edge of the beach. What were they? Were they being chased by something?–A.J., Alameda

Fishes flip and jump for a variety of reasons. Sturgeon, for example, are thought to do it for communication. The massive, Jurassic-period descendants migrate upstream to spawn during the muddy water flows of winter and spring when it’s hard to see even inches into the water. Anyone who’s ever witnessed or experienced a belly-flop at the pool (ouch!) knows that the sound of a six-foot creature slapping the water sure gets attention! What an amazing thrill to hear the slap of a massive white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) after it leaps from the water under a moonlit sky in the spring. Sturgeon happen to jump most frequently at the height of their breeding season, when presumably they want to find one another the most (queue the Barry White tunes).

The first question I have to ask when someone tells me they saw fish jumping is “how many, and how big?” On the opposite end of the size spectrum from the sturgeon are the mosquito larvae-munching rainwater killifish (Lucania parva), a guppy-sized eastern U.S. species that was first seen in California at Berkeley’s Aquatic Lagoon (that long tidal pond next to I-80) in 1958. With the ability to handle freshwater and a range of salinity as high as three times that of the ocean, they’re just about everywhere today. Whether they got here in ballast water, as eggs hitching a ride with a shipment of oysters, or mixed with mosquito-controlling Gambusia from the other side of the continental divide is beside the point – these omnipresent pigeons of the fish world earn their common name from the little ripples they make as they scurry and feed at the surface of a glassy-surfaced pond. It’s not so much a “flip” as a flitting about, and en masse you’d be fooled into thinking the little rings at the water’s surface were caused by raindrops. Most typically this happens at dusk when the water is still warm from the sun and the mosquitoes are getting active. But you were at the beach, and there were probably waves, so I’m going to abandon that hypothesis.

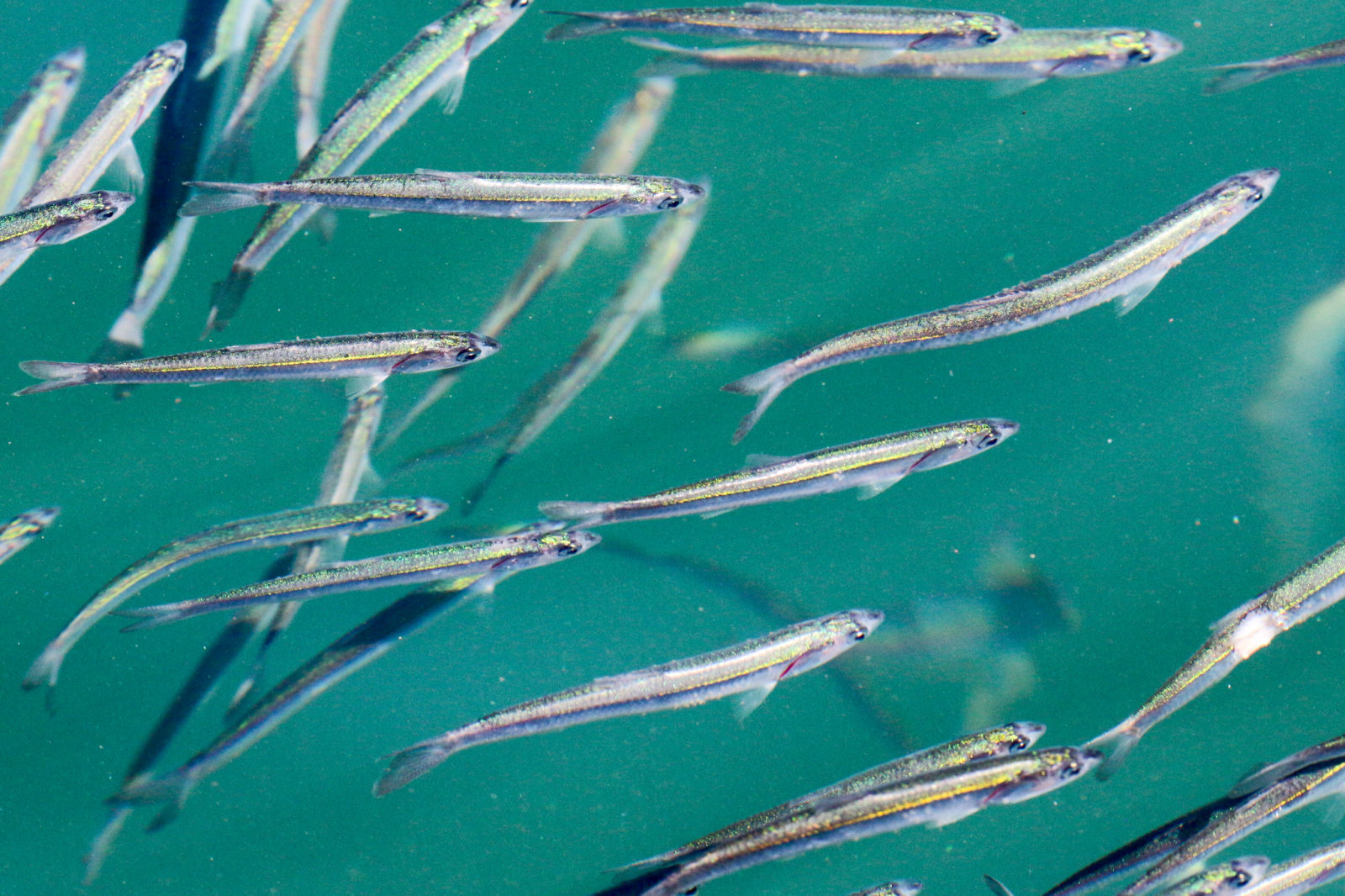

What you saw along the beach was likely a shoal of California anchovy, AKA northern anchovy (Engraulis mordax), which have been described as the most abundant fish in the Bay. Note that I said “shoal” and not “school.” There’s a slight difference. A shoal is what we call a social grouping of fish. Schooling is the “synchronized swimming” behavior a shoal might do when they tighten up en masse for protection from predators. Schooling is a kind of shoaling, not the other way around.

Whether feeding or breeding (which some anchovy shoals do year-round), as plankton feeders, anchovies not only school for protection, but to feed more efficiently. Much like a diving flock of cormorants will hunt in a row, anchovies will work together as a school to gobble up zooplankton and tiny critters in their path. The ones you saw at the beach were likely eating, spawning, or both.

If your anchovies were being chased and cornered by striped bass, halibut, or perhaps a harbor seal, you would have seen much bigger splashes. In fishing lingo they’re called “boils.” And speaking of big splashes, remember that humpback whale that was jumping in Alameda in summer 2019? It was corralling shoals of northern anchovies into an enclosed lagoon, frightening them into schools, and devouring them to bulk-up. It’s quite effective to corner prey near the shore like that!

The moral of the story? When you see things jumping by the shore, they’re probably eating, or making sweet, fishy love. Isn’t nature amazing?

Ask the Naturalist is a reader-funded bimonthly column with the California Center for Natural History that answers your questions about the natural world of the San Francisco Bay Area. Have a question for the naturalist? Fill out our question form or email us at atn at baynature.org!