Update Nov. 15, 2019: This story has been revised to reflect the city’s vote on Thursday, Nov. 14 to approve the project.

Planners, climate scientists, and environmentalists generally agree that two of the most critical measures California should take to reduce its carbon emissions are to build more dense urban housing near transit and to restore carbon-sequestering wetlands.

On Nov. 14, the East Bay city of Newark approved 469 single family homes and 2,739 parking spaces at the edge of the San Francisco Bay shoreline, on a 430-acre parcel where conservation groups and state and federal agencies have for decades hoped to restore wetlands. The project illustrates one way even straightforward and widely agreed-upon regional climate solutions can fall apart at the local level, where private landowners and city governments can act as they choose in the face of regional or global goals.

“Cities have our own powers to set out land use as we see fit,” said Steven Turner, the community development director for the city of Newark. “I think we can understand and appreciate people’s opinions to not use [Area 4] for housing or recreational amenities, but the city has consistently felt this is the type of land use they want over the years.”

The development proposal has nonetheless shocked environmental and smart-growth groups around the Bay Area. In a Nov. 8 letter to the Newark City Council, a group of 13 environmental organizations including Save the Bay, Baykeeper, the Sierra Club San Francisco Bay Chapter, The California Native Plant Society East Bay Chapter, and the Center for Biological Diversity called the project “the epitome of the type of development that should not move forward.”

“The science is clear,” the letter states, “that if we are to achieve our region’s goals of protecting and restoring biodiversity, combating climate change, and advancing climate resilience to protect our communities from the impacts of sea level rise, the preservation and restoration of Area 4 is critical.”

“There are places where development makes sense and places where it doesn’t,” said Amanda Brown-Stevens, the CEO of the Greenbelt Alliance, a nonprofit urban planning and land conservation group that also opposes the development. “If we do want to build a climate smart region, it’s not building homes on wetlands. It is building homes in many other places.”

The city says the latest development plan avoids building directly over wetlands. The project’s environmental impact report, approved by the city in 2015, allows up to 1,200 houses and a golf course, but the Mountain View-based developer Sobrato Organization has proposed building 469 houses in four “villages” on 47 acres, with 360 acres left as open space and 4.7 acres of new residential parks. City planning staff argue that everything marked as wetland in previous land surveys will remain as open space.

But environmental groups and government agencies say it’s more complicated than just marking off the wetlands and avoiding them. The US Fish and Wildlife Agency’s San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge and San Francisco Bay-Delta office both wrote letters to the city this fall asking for further environmental review and public comment, which the city declined. In early October the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board wrote a letter to the city expressing numerous concerns about the project and repeatedly calling its environmental review “inadequate”; the agency asked for a supplemental environmental review and new public comment period.

In written responses, the city dismissed concerns about the EIR by saying that, since the EIR has been certified by the city, it has to be considered final and legally adequate. The staff has also written that many of the critiques made by agencies and environmental groups are based on nonbinding goals, not legal requirements.

“I’ve been in the business for a little over 20 years, and this area was fought over as potential development for at least that long, if not more,” Turner said. “There are folks who would prefer that this area remain undeveloped. Perhaps instead of residential development and recreational development, it be turned into more restored wetlands. The city understands and appreciates those comments as well. [But] it is within the city’s land use power to designate land uses throughout the city.”

The Area 4 parcel was once a tidal wetland and upland wet grassland. It was diked and drained sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s and turned into farmland. Part of it was also converted to a managed pond for duck hunting clubs. In the 1990s, as private investment companies started to consolidate ownership of the land, the city became interested in turning the property into housing, and amended its general plan to designate the area as a “development focus.” In 1999, a city ballot measure to change the designation to open space, conservation and agriculture failed, which, city staff wrote in a recent report, “confirmed the vision for Area 4.”

Under the plans Stevenson Boulevard, which currently ends at the edge of the parcel, would be extended into the new development, where the developer proposed building a 30-foot lighthouse “to create a strong identity for this new residential development.”

“For me, a lighthouse was a warning of what the shoreline was,” said Jana Sokale, a Newark resident and member of the Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge, which sued the city in 2013 over the first project EIR. “The lighthouse is a warning for any resident who thinks they want to buy a house out there.”

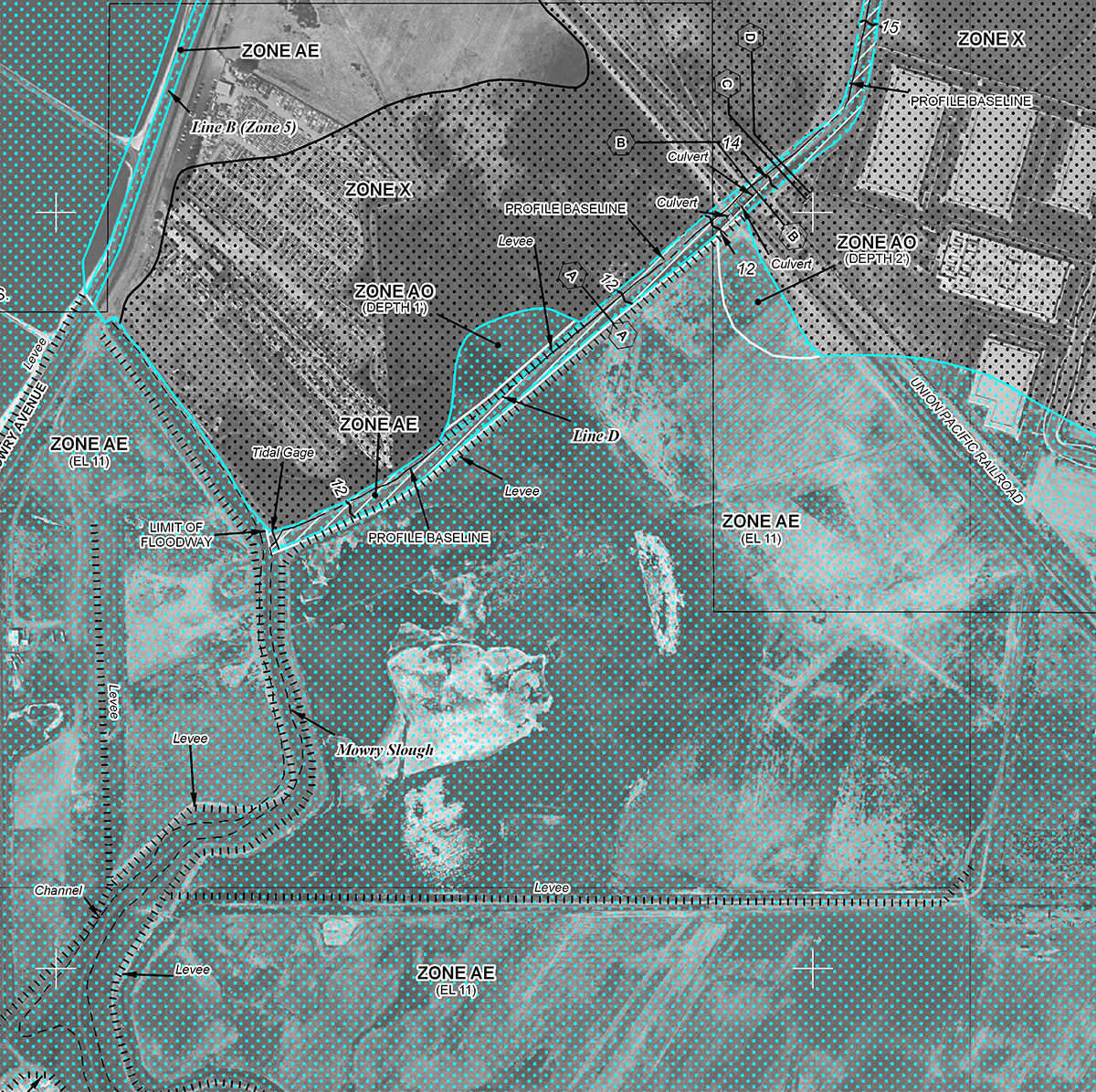

The problem, Sokale said, starts with the rising Bay. Currently most parts of Area 4 are in what the Federal Emergency Management Agency designates an “AE” flood hazard zone, meaning they would be inundated in a so-called 1-percent storm.

Area 4 is protected from Bay water by pumps and a network of public and private levees. To lift the new houses out of the flood zone will require importing 1.6 million cubic yards of fill to raise the land by 15 feet. But the developer proposes raising the area under the houses, not the open space — creating a riprap-protected island of housing over the still-flood-prone wetlands below. Sokale said that when the sea level rises, or the aging farm levee fails, or the pumps fail, the wetlands will drown, the rare species living in them will die, and the houses will stand alone on a literal island of fill, one she said would be susceptible to earthquake collapse. “High liquefaction area,” Sokale said. “Near the Hayward Fault. In former tidal wetlands. You want to buy a house there, don’t you?”

In its October letter, the Regional Water Quality Control Board wrote that the EIR the city had certified “fails to adequately address cumulative impacts from proposed Project activities on local and regional flood risks, which are likely to be exacerbated by climate change.”

The city staff disagreed, concluding, “the risk of flooding is low.”

The project area is also home to four special status species: the salt marsh harvest mouse, California Ridgway’s rail, California black rail, and burrowing owl. The city concluded that based on surveys in 2006 and 2007 by environmental consultants at HT Harvey, the development won’t extend into the potential habitat for any threatened or endangered species. But the Water Board and US Fish and Wildlife Service have both disagreed, saying the data is old and that survey methods, particularly for the salt marsh harvest mouse, have changed in the last decade.

The USFWS also expressed concern about the loss of potential upland habitat. As sea level rises, tidal marshes will try to “migrate” inland. Because the area around the Bay is generally so developed, though, there’s often not space for marshes to retreat, making undeveloped areas next to tidal wetlands particularly valuable to conservationists. Scientists and conservation groups have identified the restoration of Mowry Slough and adjacent upland habitats as a priority since the late 1990s, and numerous groups have called for restoring the site and adding it to the neighboring Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge.

In the 2015 Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals Update, a report signed off on by dozens of scientists from around the Bay Area, Area 4 was part of a segment the document labeled a “unique opportunity” to “restore historic tidal marsh–upland transition zones.”

But, the city replied, those are goals, not requirements, and unless the state or region sends some strong signal telling it not to, the city can do what it wants with its own land. And what Newark wants to do in Area 4, and has wanted to do for more than 20 years, is build low-density houses. “It’s in the city’s best interest to have laws that conform with the laws the state sends down,” Turner said. “Newark would do the same thing if the state told us there’s a limit on development on a certain area within the shoreline, or that you cannot artificially increase elevation on a shoreline for housing. Whatever guidance the city receives, we will do our best to comply.”

Turner compared sea level rise guidance to earthquake preparedness codes. For earthquakes, the state sets building codes that cities then follow when they build new houses. Turner said there’s no equivalent from the state or even the region on what to do about sea level rise — just generally expressed goals about high-density and near transit. Meanwhile, the city has housing targets to meet and land use decisions to make.

SPUR Sustainable Development Policy Director Laura Tam said the lack of responsible housing development over the years has turned the Bay Area’s housing affordability challenge into an environmental issue.

“We are having a housing crisis in the Bay Area, and I can see how for some that might lead you to think all housing is good,” she said. “We have to solve the housing problem and make that work, then it won’t be disguised as a fight over trees versus housing. We have to have both.”

Tam and Brown-Stevens both said it’s particularly challenging to oppose housing developments on environmental grounds, because the line “we support housing but not in this specific place” has been so often co-opted by residents or neighbors who simply want to block any development. Brown-Stevens said part of the solution she sees is regional urban planning and environmental groups advocating for climate-friendly housing projects. Tam suggested looking at Newark’s neighbors, praising Fremont, Union City, and San Leandro for adding transit-oriented development in recent years.

“This should be a regional conversation and regional solutions,” Brown-Stevens said. “So how can we move away from trying to stop these individual developments, and collaborate on a strategy that really is a regional shoreline protection strategy that will reduce our flood risk overall, by restoring and developing in the right way along the shoreline?”