During the statewide COVID-19 shelter-in place-order, tens of thousands of Bay Area residents have sought refuge in the region’s parks—on bike paths, trails and beaches. But that desire has, according to local officials, run afoul of public health.

Last week, in response to complaints and an outpouring of social media outrage, governor Gavin Newsom announced a “soft closure” of 36 State Parks and beaches in California, 26 of which are located in the Bay Area. On Sunday March 29, Newsom drastically expanded that order, closing all California State Park parking lots indefinitely, and parks entirely in several counties . “I had a little anxiety as all of you did, watching the news of all those crowds and folks at our parks,” Newsom had said in a press conference on March 21. “We can’t see what happened over the weekend happen again.”

Max Korten, director and general manager of Marin County Parks and Open Space, said the decision to close Marin County’s 18,000 acres of public lands to cars on March 22 was based on reports of large crowds in small beachfront communities such as Stinson Beach and Point Reyes Station, where people were congregating in local markets buying up picnic supplies. “Any decision about our parks is best when we have years to think about it,” Korten said. “We didn’t have that luxury in this case. It’s been a very abbreviated process, but one that was necessary.”

Amid the pandemic, local leaders and land managers are being forced to act on the fly, with limited data, in an attempt to limit the spread of coronavirus. But, as that effort is being carried out, old patterns of inequity are re-emerging—particularly when it comes to access to public lands. The rolling closures have compounded problems of crowding and access. Sonoma County pre-emptively decided to close its own parks after fearing that Marin County’s closures would “creat[e] a likelihood that persons living in those counties will travel to Sonoma County for outdoor activity and recreation.” Bay Nature readers reported observing similar spillover in the East Bay, where the East Bay Regional Park District closures combined with newly free access to East Bay Municipal Utilities District land led to crowded trails on EBMUD open space.

As the statewide shelter-in-place order approaches its third week, it’s becoming increasingly clear that the decision to curtail access to open space is falling most heavily on low-income, densely populated urban communities with scant access to open space. Residents in wealthy hamlets around the region can still travel by foot or bike and access to millions of acres of open space. As the Santa Rosa Press Democrat reported on Monday, Sonoma County’s director of emergency management drove his family to the beach after the county closure. Meanwhile, the Bay Area’s city dwellers are left with small pockets of parkland—pockets that are sure to grow smaller in the days, weeks and, perhaps, months ahead.

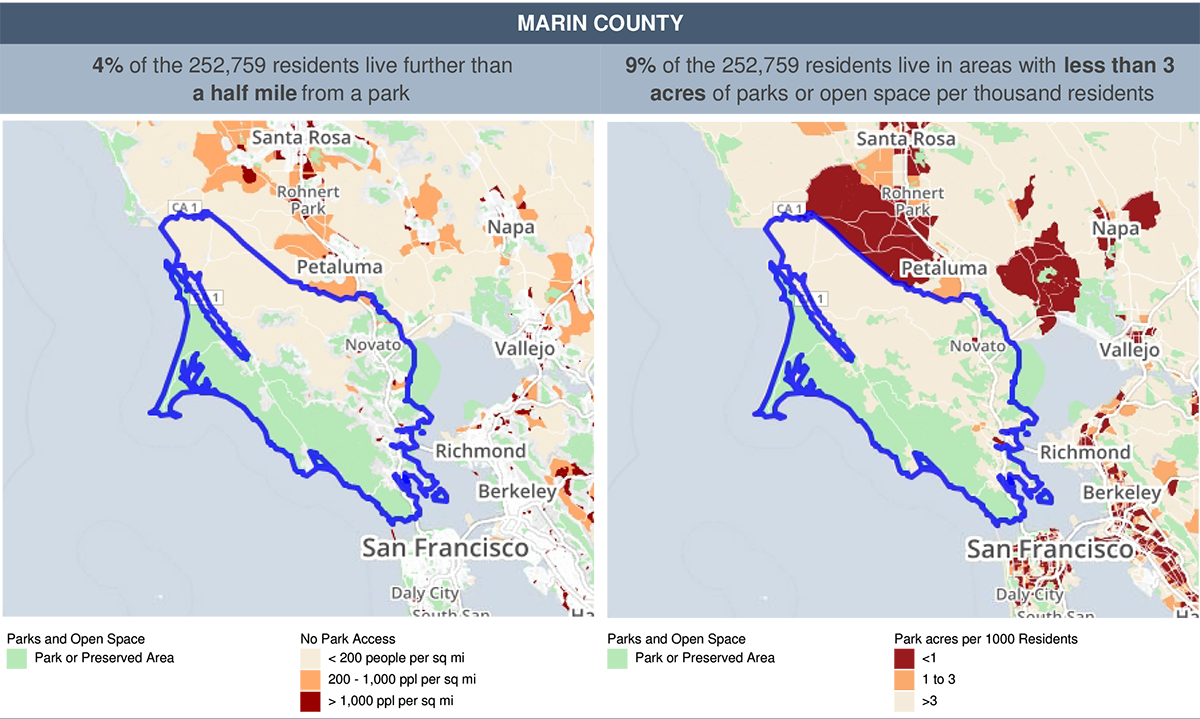

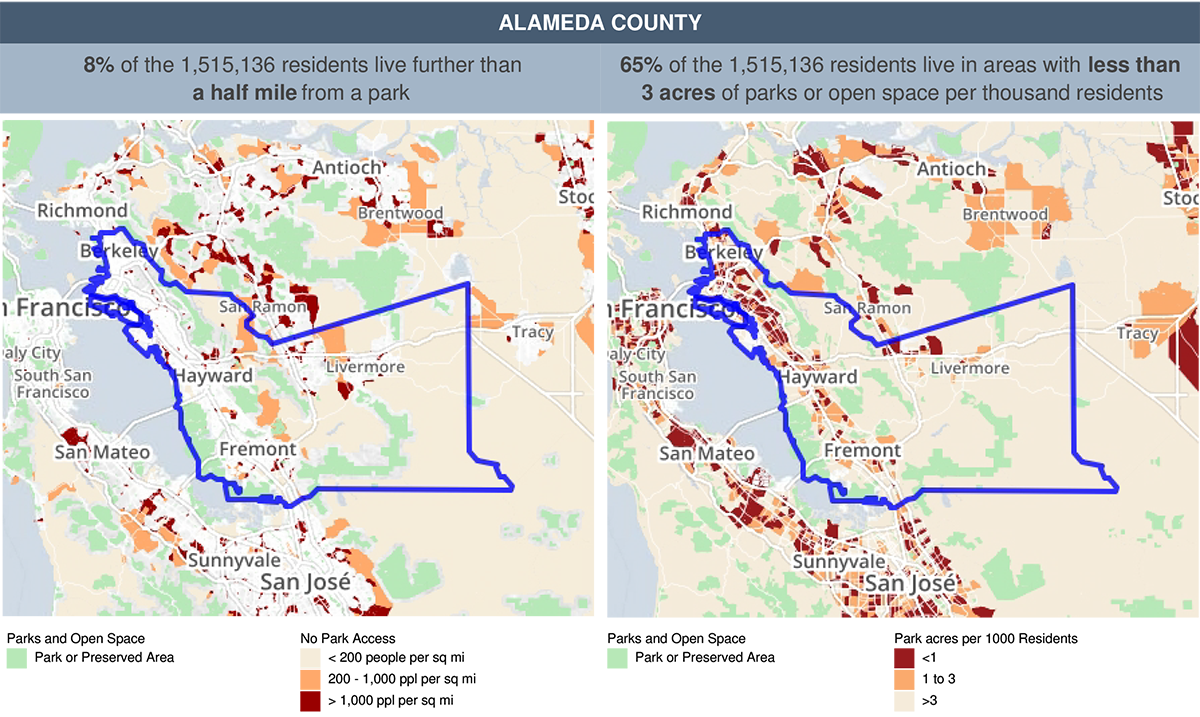

In the Bay Area, access to open space is, to a large degree, a function of household income. Take, for example, the city of Oakland, where 18.7 percent of residents live at or below the poverty line and 80 percent live in areas with less than three acres of open space per 1,000 people; in Mill Valley, by contrast, 4.6 percent live in poverty and not a single resident lives in a zone with less than three acres of parkland per 1,000 residents.

Access to parks is not a luxury but a necessity for health, says Jon Christensen, assistant professor at UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability “Lack of access to nearby parks has been found in study after study to be linked with negative health outcomes—low birth weight, asthma, diabetes.” These trends, he added, disproportionately impact low-income communities of color. These conditions also put residents at higher risk of suffering the worst effects of COVID-19.

“It’s well documented that access to nature parallels income and, in some cases, race,” said Nooshin Razani, a pediatrician who directs the Center for Nature and Health at Benioff Children’s Hospital in Oakland, echoing Christensen’s sentiments. “We need to fight for the right for people who don’t have [nature] right outside their front doors to get to parks.”

One outlier, so far, is the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority, which serves a large and diverse population, and which, to date, has not shuttered a single park in response to COVID-19. Silicon Valley has been one of the hardest-hit areas in the state, but instead of blanket closures, the SCVOSA has promoted responsible use—staying close to home, avoiding crowded trailheads and maintaining social distance. Using social media, Santa Clara officials have advocated safe open space use with the #loveyourparks6feetapart hashtag.

“The Open Space Authority strongly believes that connecting people to nature and outdoor spaces is more important than ever,” said Andrea Mackenzie, the Authority’s general manager. “We want to keep preserves open and continue to provide this invaluable service to the public.”

Over the last week, Mackenzie said, park staff has observed noticeable improvement in people practicing social distancing and a drop in non-household meetups. “The public seems to be responding to our messages and is grateful for access to nature in this unprecedented time,” she said.

So what is the best approach—imposing blanket closures or allowing the public to self-regulate? It depends upon whom you ask.

“Parks are a wonderful antidote to what’s going on,” said Marin County Parks’ Korten. He said he recently came across accounts of city council meetings held outdoors during the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. But, he says, the growth of the Bay Area has made the possibility of using parks, even the largest ones, as sanctuaries from COVID-19 an untenable proposition. “You realize that everyone is off from work and has this pent-up energy that can create a potentially harmful situation.”

Rue Mapp, founder of Outdoor Afro, a nonprofit that advocates for inclusive outdoor participation and leadership, says that park managers like Korten will be forced to accomplish a difficult balancing act in the weeks ahead—one that requires short-term tactics to minimize risk while seeking long-term strategies to restore access. “Unless parks have the infrastructure and staff to enforce social distancing, the responsible thing to do is close them for a short-term basis,” she said. “But if this goes on for a longer period of time and access becomes even more limited, we’re going to have to dig in a little deeper, to make sure that access is available and equitable.”

Part of ensuring equity will mean finding ways to get people into nature without getting behind the wheel. Jon Christensen said that research he’s done shows that 90 percent of California visitors to the coast travel by automobile. In the time of coronavirus, however, parking lot closures (as well as bathrooms and visitors centers) are seen as a critical step in reducing crowding and minimizing the possibility of germ exchange. “When park managers close parking lots, even for good reasons, they are also effectively denying access to the vast majority of Californians,” Christensen said.

Public space can be utilized safely if visitors are properly informed about how to recreate safely, experts say. The risks of visiting trails and beaches can be minimized by strictly adhering to the six-foot social distancing guidelines and voluntarily bypassing places where large groups are apparent. “[If] you go to Lake Merritt or go to Ocean Beach, stay away from the crowd,” Dr. Sajan Patel, an assistant professor of medicine at the UCSF School of Medicine, told KALW reporter Marissa Ortega-Welch on March 20. “If you’re at Ocean Beach and it’s completely crowded, I would avoid it. And hopefully everyone there knows that they should just be either by themselves or with that housemate. In general, the less people together, the better.”

San Francisco has emphasized visiting local parks, and on one score, that’s possible: 97 percent of city residents live within a half mile of a park, according to data from the Parks for All Californians Park Access tool. But while the parks are widely distributed, the same dataset says there’s not enough of them by acreage: 83 percent of people in San Francisco live in areas with less than 3 acres of open space per thousand residents. Compare that to Corte Madera, where 98 percent of residents live within half a mile of a park and every resident lives in an area with more than 3 acres of open space per thousand residents.

It’s hard not to feel that in this time of crisis hundreds of thousands of Bay Area residents are seeing access to parks restricted in part because of decades of inaction on equitable access to open space. Must we abandon parks and beaches entirely until the pandemic subsides? Can we get back to nature without getting into the car?

Some have suggested a rationing system for park visits that would use, say, the last digit of one’s residential address to assign days for park visits. Amber Hasselbring, executive director with San Francisco-based environmental non-profit Nature in the City, says that the safest approach for city dwellers—cold comfort though it may be—is for people to look for the natural world right outside their front door. “We advocate for exploring nature where you live,” Hasselbring said. “Now is the time to find new pocket parks, neighborhood trees, the gardens outside people’s front doors.”

Mapp concurred. “Nature is everywhere,” she said. “We are nature. I want to encourage people to explore nature close to home. There is a lot we can experience right in our own backyards.”