It’s seldom easy to take a deep, relaxing breath here in the San Joaquin Valley. The dust and smoke from industrial processes, farming operations, construction activities, wood stoves, outdoor burning, and the cars and trucks that barrel down local roads and regional highways keep the Valley at or near the top of the lists of most-polluted air basins in the United States.

Perhaps the most dangerous ingredient in the toxic soup of the Valley’s air is the collection of microscopic particles known as PM-2.5, those particles with diameters of 2.5 micrometers and smaller, or about one-thirtieth the diameter of a human hair. PM-2.5 emissions in Fresno County average about 25 or 30 tons per day, enough to pose significantly elevated risks of decreased lung function, aggravated asthma, and heart attacks to the county’s population.

Thirty tons of microscopic dust and smoke particles sound like a lot. But during the Creek Fire just up the slope of the Sierra Nevada from the Valley floor, with around 2,000 tons of woody fuels burning per acre across much of the 300,000-plus-acre area of the fire, emissions no doubt reached into the millions of tons per day in Fresno County. At times like these, it’s no surprise to me when, several miles away from the flames, I experience some of the classic effects of exposure to smoke: I cough, my eyes sting, my throat itches, my head aches, and I’m generally fatigued. Even with all that, I consider myself fortunate, as a sixty-something man with a personal history of asthma and other respiratory issues, to have avoided (so far) the heart attacks and strokes that the choking levels of smoke from this kind of megafire can trigger.

So I understand, then, why even most of those who advocate for increases in “good fire,” or prescribed fire — for the way it reduces fuel hazards and the risk of uncontrolled wildfires, as well as for fire’s ecological benefits — even they tend to treat smoke only as a pernicious nuisance, a pollutant that must be managed and minimized.

And yet, there are reasons to push back against this notion, especially if we expand our view of planned fires to include not only prescribed, hazard-reduction burns but also prescribed fire’s predecessor and — in many ways — inspiration: Indigenous cultural fire.

Many prescribed fire practitioners, looking for ways to expand their window of opportunity to implement planned burns, point out that their smoke is not as heavy as the smoke from large-scale wildfires. It’s the idea that, one way or another, fires and smoke are inevitable but we have a choice: Would you like your smoke a little bit at a time or all at once? Would you like a few scattered, localized, intermittent showers of pulverized ash or a suffocating, life-threatening deluge that turns the Bay Area sky orange and threatens thousands of lives?

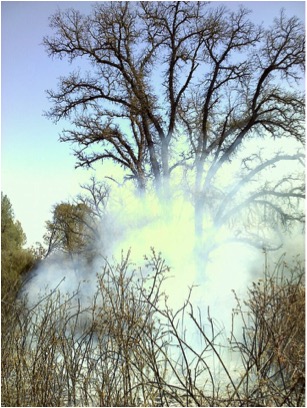

Indigenous cultural practitioners take things a step further to argue that smoke is good for the ecosystem. For example, smoke applied to oak trees curtails tree pathogens and disease, stimulating greater production of acorns. A good crop of acorns directly supports a whole host of herbivores and omnivores, such as deer, bear, woodpeckers, and quails, and acorns indirectly support predators such as the endangered Pacific fisher and spotted owl. These benefits of smoke, well-known among Indigenous people, explain why, a decade ago, a tribal elder said to me of a group of oaks besieged by mistletoe and struggling for water and sunlight in competition with younger, taller conifers, “We’ve got to put some smoke on those trees.”

Beyond their positive effects on ecosystem health, frequent Indigenous cultural burns — even with their attendant reduction in air quality, may also positively affect people’s health. In a recent Australian study of Aboriginal people with COPD, researchers were surprised to find that increased local fire frequencies can be correlated to fewer episodes of exacerbated respiratory symptoms:

People living in the regional and remote communities in the study area are constantly exposed to environmental smoke due to local vegetation fires, during which they are exposed to poor air quality, which can give rise to respiratory symptoms. In this study we made an attempt to explore the fire frequency in the remote and regional areas and the numbers of exacerbations and hospital admissions. Given the previous literature on the effects of ambient biomass smoke on cardiorespiratory health, our results were unexpected. Communities with higher average fire frequency had significantly fewer average exacerbations per year. More studies are needed to better understand this relationship, which could be direct or indirect. For example, this result could be an indication of the positive influence of traditional burning on the community surroundings. Areas with more frequent fires have lower vegetation biomass (fuel load), which may translate into less intense fires and consequently better air quality during fires and less negative effects on respiratory symptom exacerbations. Another indirect effect could be related to the better physical and mental health of Aboriginal people actively working in the management of their land.

Maybe we need a broader definition of health. Moderate doses of smoke can foster healthier plants and a more abundant ecosystem, one less prone to hosting megafires with their overdoses of smoke. If Indigenous fire- and smoke-tenders could bring their cultural burning programs back to scale across the landscape, the more productive plants and more abundant animals that result — and the physical exercise that comes along with reestablishing a cultural fire regimen — could contribute to a healthy, wholesome diet and lifestyle that counters the risk factors for diabetes and other illnesses and health conditions so prevalent in many Indigenous communities today.

Yes, breathing too much smoke can be extremely detrimental to our health. But if we inquire further, perhaps we’ll find that fire and smoke have their health benefits, too — for us and for the land. Maybe we’ll all come to agree, eventually, with the Traditional Knowledge Revival Pathways project in Australia project that fire and smoke can lead to healthy country and healthy people:

During a rainy spell I sometimes get to the point of thinking, “You know, I sure am tired of all this rain, but I know we need it — for now I’ll stay inside or, if I need to go out, I’ll throw on a raincoat or grab an umbrella, just in case I need it.” If we can get through our current pandemic of wildfires and their lethal smoke-storms, and if Indigenous people can re-establish their cultural fire regimens, perhaps, during a future smoky spell, I’ll be able to start to say to myself, “You know, I sure am tired of all this smoke, but I know we need it — for now I’ll stay inside or, if I need go out (maybe even to see if I can pitch in and help with the burns), I’ll grab an N95 mask, just in case I need it.”