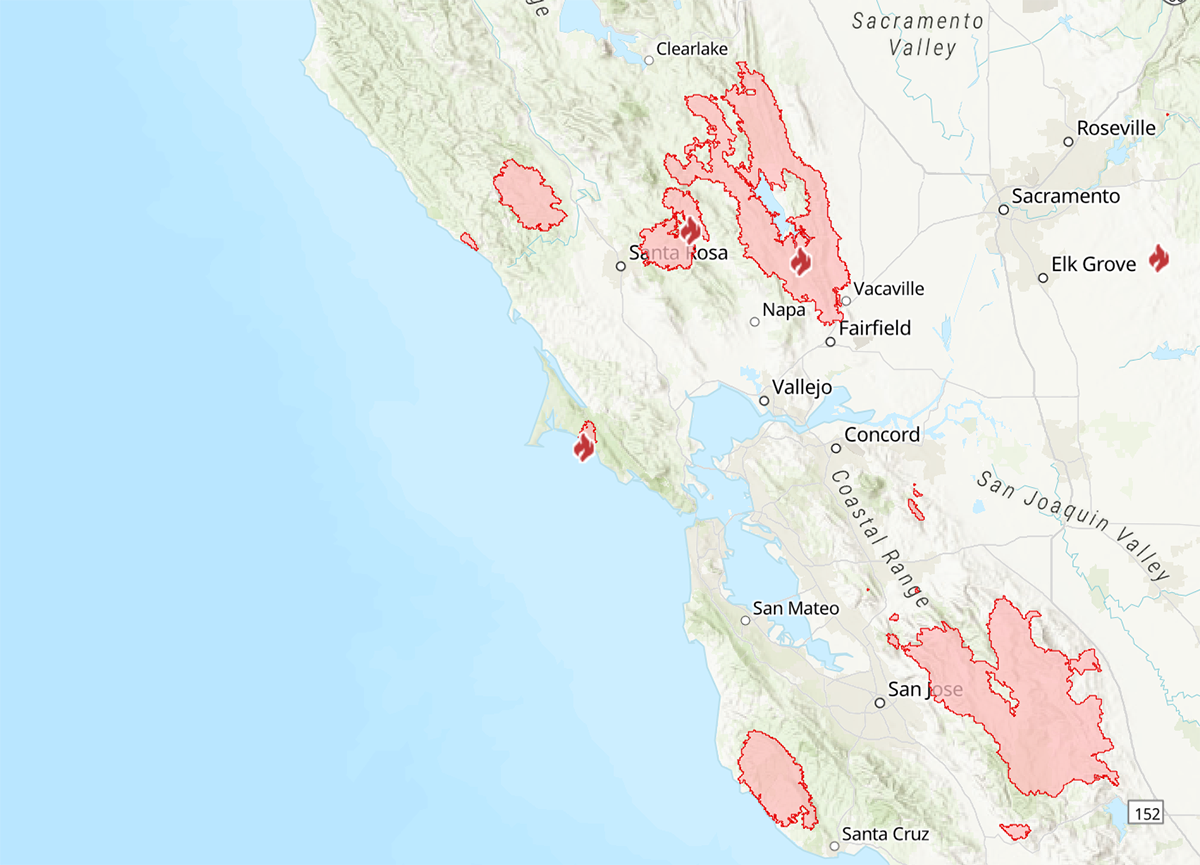

Close to a million acres have burned in the greater Bay Area in the last six weeks, including hundreds of thousands of acres in public parks and protected open spaces. As the Glass Fire continues to burn through several state and regional parks, as well as residential and agricultural areas in Napa and Sonoma counties, land managers and stewards have begun to assess the ecological effects of the massive lightning-ignited SCU, CZU, and LNU Lightning Complex fires.

SCU Fire

A total of 396,624 acres have burned in the Diablo Range since the rare mid-August thunderstorm started approximately 20 individual fires in the East Bay, making the SCU Complex the third largest wildfire in California since at least 1932.

In the East Bay Regional Park District, the fire burned in the Ohlone Wilderness, a remote preserve in Alameda County only accessible by way of the Ohlone Wilderness Trail, as well as Morgan Territory and Round Valley, located in the Deer Zone of the fire in Contra Costa county. Fires also touched parts of Sunol Regional Wilderness and Mission Peak. “It is primarily wildlands that the fire burned through,” said EBRPD Fire Chief Aileen Theile.

Mission Peak has already reopened. Before the other parks can reopen, district staff must conduct a full assessment of damage and safety hazards, such as falling tree limbs, smoldering inside trees, erosion risk in places that have lost vegetation, and fire breaks in need of restoration, said Public Information Supervisor Dave Mason. “We want the parks open as soon as possible,” said Mason. “But we can only do that once they’re deemed safe.”

Further south in the Diablo Range roughly two-thirds of Northern California’s largest state park, Henry W. Coe, burned. Much of the fire burned at a low heat and intensity, sparing seed banks and the canopies of most of the oaks and pines that grow there, California State Parks Natural Resource Manager Wes Gray wrote in an Initial Natural Resource Assessment published by the Pine Ridge Association. “It burned very similar to how a planned prescribed burn would,” he wrote, emphasizing the positive role of fire on the park’s ecology. “Many of the hillsides burned in a perfect mosaic pattern leaving green unburnt vegetation. This will provide refuge for wildlife and lead to an increased diversity in plant age class over time… and the next spring should be a banner year for wildflowers.”

State Parks Information Officer Jorge Moreno said that the agency does not yet have a timeframe for when Coe, or any of the closed state parks around the Bay Area, will reopen.

The Nature Conservancy’s Mount Hamilton Project protects 101,000 acres of rangelands through conservation easements around the area, about 24,000 acres of which burned. “It’s a little hard to talk about when the fires are still burning and people are still evacuated from their homes,” said TNC Senior Forest Ecologist & Fire Manager Ed Smith. But, he said, the return of fire to these ecosystems “can really help increase their productivity, and rejuvenate nutrient cycling, and increase resilience to drought.”

Oak woodlands tend to respond quickly with annual grasses in the spring, he said, but TNC ecologists will be watching over the next couple years to see how some of the burned oaks regenerate.

The Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton was the site of a dramatic firefighting effort to save the 130-year-old observatory with its expensive equipment and priceless astronomical records. Just down the slope to the west, the UC Natural Reserve System’s Blue Oak Ranch Reserve headquarters served as a station for Cal Fire to cut fire breaks, conduct back burns, and lay fire retardant to prevent the spread of the fire into east San José. UCNRS Director of Communications Kathleen Wong said that although the fire breaks Cal Fire had to cut through the landscape will need to be restored to prevent erosion, there are “still a lot of big trees” left on the reserve’s grasslands.

The adjacent Joseph D. Grant County Park was also a critical site for stopping the fire’s eastward expansion. “It’s really something to see your park burn,” said the park’s acting Senior Ranger Aylara Odekova. “But I recognized the value that fire brings to the land. I was more worried about people and their property.”

Odekova said the park has been conducting prescribed burns there for the last decade. Although 3,700 acres of the park burned, it’s critical structures were untouched. By early September, crews were working to make the park safe for the public by clearing trails of large trees that had fallen or were at risk of falling, and it reopened on September 21.

CZU Fire

Within just a few days of the mid-August lightning storm, several small fires in the Santa Cruz Mountains had merged into the CZU Lightning Complex, which ultimately burned 86,509 acres.

“It’s devastating,” said Dylan Skybrook, the Manager of the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network. “The scope of the damage is mind-boggling.”

Skybrook said he has heard from members of the network, which includes individuals and organizations, that the intensity of the fire varied throughout the affected areas, many of which have not burned in many decades. “Some things burned really severely, and other things not so much,” he said. “It’s a really different picture throughout the region.”

Sempervirens Fund Director of Conservation Laura McLendon, who has been back to see some of the burned landscapes, says that in low-intensity areas, where charred understory and forest canopy remains, the fire will be “pretty rejuvenating.” She has already seen new growth and ferns popping up at the base of redwood trunks. In other areas, however, the fire burned so hot and intense, that only ash and trees that look like telephone poles remain.

Sempervirens Fund, which protects about 11,000 acres in San Mateo and Santa Cruz counties, had 94 percent of its land burn. “At first all I felt was despair and anxiety,” McLendon said. “But in the last few weeks, especially having been out to Big Basin and other Sempervirens properties, the hope is in seeing that there’s new growth already there… It’s not just a pile of ash. There’s green canopy that’s left, and those trees are going to live.”

The CZU fire burned through almost all of San Vicente Redwoods, Sempervirens Fund’s largest property, which is scheduled to open to the public next year. San Vicente partners, which include Land Trust of Santa Cruz County, Peninsula Open Space Trust, and Save the Redwoods League, will meet with experts to see what modifications, if any, need to be made to the trail’s design to accommodate the post-fire ecology, McLendon said. But she said she’s “cautiously optimistic” that San Vicente’s first trail will open in late 2021 as planned. “A lot has to go right to make that happen, but we may not have lost as much time on this project as we initially thought,” she said.

Big Basin State Park, California’s oldest state park, burned extensively, as did the neighboring Butano State Park, which is home to second- and third-growth redwoods, Cascade Ranch, the inland unit of Año Nuevo State Park, the Fall Creek Unit of Henry Cowell State Redwoods, and a small portion of Wilder Ranch State Park. Moreno, a California State Parks spokesperson, emphasized the importance of fire for maintaining healthy forests and the ability of redwoods in particular to withstand low-intensity burns. As with Henry Coe, State Parks does not yet have a timeframe for reopening Big Basin, Butano, or the directly-affected areas of the other three parks, at least two of which suffered structure loss, Moreno said.

Recovery efforts in the mountains will include erosion control, water quality monitoring, hazard tree removal, soil remediation in places where structures have burned, and re-vegetation with native plants, said San Mateo Resource Conservation District Executive Director Kellyx Nelson. To encourage fire resilience, San Mateo RCD and others will pursue long-term forest assessment and management efforts like reducing fuel loads, helping young healthy trees thrive, and improving roads for fire vehicle access.

Nelson said she hopes that the historic fire has helped increase public awareness about the need to invest in forest resilience. “I think that there’s been a perception that if we fence off nature and let nature run its course, that that’s what’s best for the forest,” she said. “But we’ve altered the variables so much by preventing fire, by changing the climate… We need intervention to bring these forests back into the balance.”

LNU Fire

Like the other lightning complexes, the LNU began as numerous fires that quickly grew and merged into one huge conflagration, which formed a ring around Lake Berryessa, labelled the East Zone of the LNU Complex by Cal Fire. West of Highway 101, the Walbridge Fire and smaller Meyers Fire burned in Sonoma County. The LNU Complex eventually grew to 363,220 acres, and is now the fourth largest wildfire in recent California history.

The Land Trust of Napa County had approximately 6,400 acres across eight preserves burned in the LNU Complex, not including the private lands that they protect through conservation easements, said Stewardship Program Manager Mike Palladini. Palladini said that, as in other places, the fire severity was mixed. While there are places “where its charred stems and black earth,” Palladini said, those high-severity flare ups are “interspersed with unburned areas and low- or medium-intensity areas.”

LTNC has to conduct erosion risk assessments, restore fire lines, clear roads, and document damaged infrastructure, Palladini said, before LTNC staff can “start shifting toward monitoring the ecological response of the fires and doing whatever we can to jumpstart the ecological recovery if there’s any intervention needed.”

Several years of fire, with lost lives and property, have taken their toll on the Napa community, including LTNC staff who both live and work in the county, Palladini said, so “it’s good to know that we don’t have to worry about, in many cases, our plant communities not coming back.”

After the 2017 fires, LTNC staff documented several fire-following species in their ecological surveys, including fire poppies, bonfire moss, and breeding lazuli buntings, which flocked in unprecedented numbers to Mount George to take advantage of re-sprouting shrubs for nest material and the influx of insects from a post-fire wildflower boom.

Palladini said he does worry, however, about the increasing frequency of wildfires due to climate change. Even though the many native plant species are fire-adapted, they need sufficient time between burns to resprout and reseed in order to withstand wildfires over time–especially in a warmer, drier climate. Shortened fire return intervals, he said, can convert native chaparral plant communities into non-native annual grassland. LTNC lands burned just three years ago in the 2017 fires, and just as LTNC staff was returning to the landscapes burned in the LNU Complex, the Glass Fire broke out. “It’s surreal that [another wildfire] happened again so quickly,” Palladini said. “Our little part of the world seems to be getting hit so hard this year.”

A significant portion of the land affected by the LNU Complex is in the Berryessa-Snow Mountain National Monument, which is owned and managed by the Bureau of Land Management. The BLM’s website states that Cedar Roughs Wilderness, Knoxville Management Area, Berryessa Management Area, and portions of Cache Creek Natural Area are closed due to the LNU Complex fire. BLM Public Affairs staff did not respond to a request for more information about burns on the property.

The California Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, and UC Natural Reserve System also hold land in the area, much of which has burned in the last five years in the County (2018), Wragg (2015), and Rocky (2015) wildfires.

The Walbridge Fire burned through more than 50,000 acres of rugged forest slopes and canyons in northwestern Sonoma County. But Christopher Adlam, a PhD candidate at UC Davis focusing on the revitalization of Indigenous burning practices and post-fire ecology who helped fight the fire, described a “mixed” fire intensity in Armstrong Redwoods State Park and Austin Creek State Recreation Area. “Everything I was seeing was really good in terms of ecology,” Adlam said. “I don’t think I had seen a single old-growth redwood that had died.”

Despite dramatic headlines, there have been a lot of great ecological benefits from recent CA fires. I’m mopping up after the Wallbridge Fire with a hand crew at Armstrong Redwoods SP; fire effects here are very positive. The redwoods (& madrones/tanoaks/maples) are doing great! pic.twitter.com/EnLI1mYo17

— Christopher Adlam (@cxadlam) September 2, 2020

The patchy burn pattern there will produce a great habitat for species like woodpeckers that utilize burnt habitats, he added.

News accounts tend to focus on total acreage burned, and this year’s record-setting totals. But Adlam said, that’s “a very small part of the story… what’s most important is what’s left after the fire.” Once burned open spaces like Armstrong Redwoods reopen to the public, Adlam said he hopes people visit these parks ”to see that burned areas are not a disaster, they’re actually thriving.”

Woodward Fire

The Woodward Fire, also ignited by the mid-August lightning strikes, burned nearly 5,000 acres of thick coastal scrub and old growth mixed conifer forest between Limantour Road and Bear Valley Trail in Point Reyes National Seashore, some of which also burned in the larger 1995 Mount Vision Fire. The Burned Area Response Team, made up of federal experts, are assessing erosion risk and damage to salmon and other endangered species. Parts of Point Reyes have already reopened; only the areas directly affected by the still smoldering Woodward Fire remain closed.