Although few of its more than 2 million annual visitors may realize it, behind the majestic coastal bluffs and sprawling pasture of Point Reyes National Seashore lies a history of conflicts, compromises, and competing park priorities.

Ranchers and community leaders fought the establishment of the National Seashore itself, local food advocates fought for the continuation of an oyster farm in a designated wilderness area, and wildlife activists have fought against the fencing-in of native tule elk on the Seashore’s elk reserve. Most recently, in 2016 three environmental groups sued the National Park Service, alleging that the agency was planning to extend cattle grazing leases without evaluating the impacts of ranching on the Seashore’s unique ecology.

In a settlement the following year the NPS agreed to conduct an environmental review before deciding on a final plan for how, or if, the beef and dairy ranches would continue to operate in the Seashore. A final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was released in September, and the NPS is expected to announce its management decision early next year.

It’s unusual, although not unique, for commercial ranches to operate on National Park system lands. At Point Reyes, which was once home to California’s largest dairy operation, cattle ranches have been a feature of the landscape for the last 150 years.

Nona Dennis, a board member of Marin Conservation League, said that in the 1962 founding legislation, Congress identified three main reasons for establishing a National Seashore on the Point Reyes peninsula: “One was natural beauty, one was scientific and historic interest, and then recreation.” At that time, Dennis said, allowing the continuation of agriculture, at least in the short-term, was a practical necessity for saving the beloved 71,000-acre landscape from residential development.

From there, she said, the Seashore’s management priorities “evolved over time.” In the 1980s, the NPS began viewing ranch preservation as part of its mission to protect the Seashore’s historic resources and “cultural landscapes.” Today, most of the ranches are part of Historic Districts listed on the National Register of Historic Places. “It was never envisioned as a single purpose park,” Dennis said. “That’s why we believe you can balance and incorporate various elements of value.”

David Lewis, the director of Marin UC Cooperative Extension, which provides ranch management research and education, said the Seashore’s working cattle ranches offer “an incredibly valuable opportunity to see how humans are part of the ecosystem and how we strive to be better stewards of the ecosystem.”

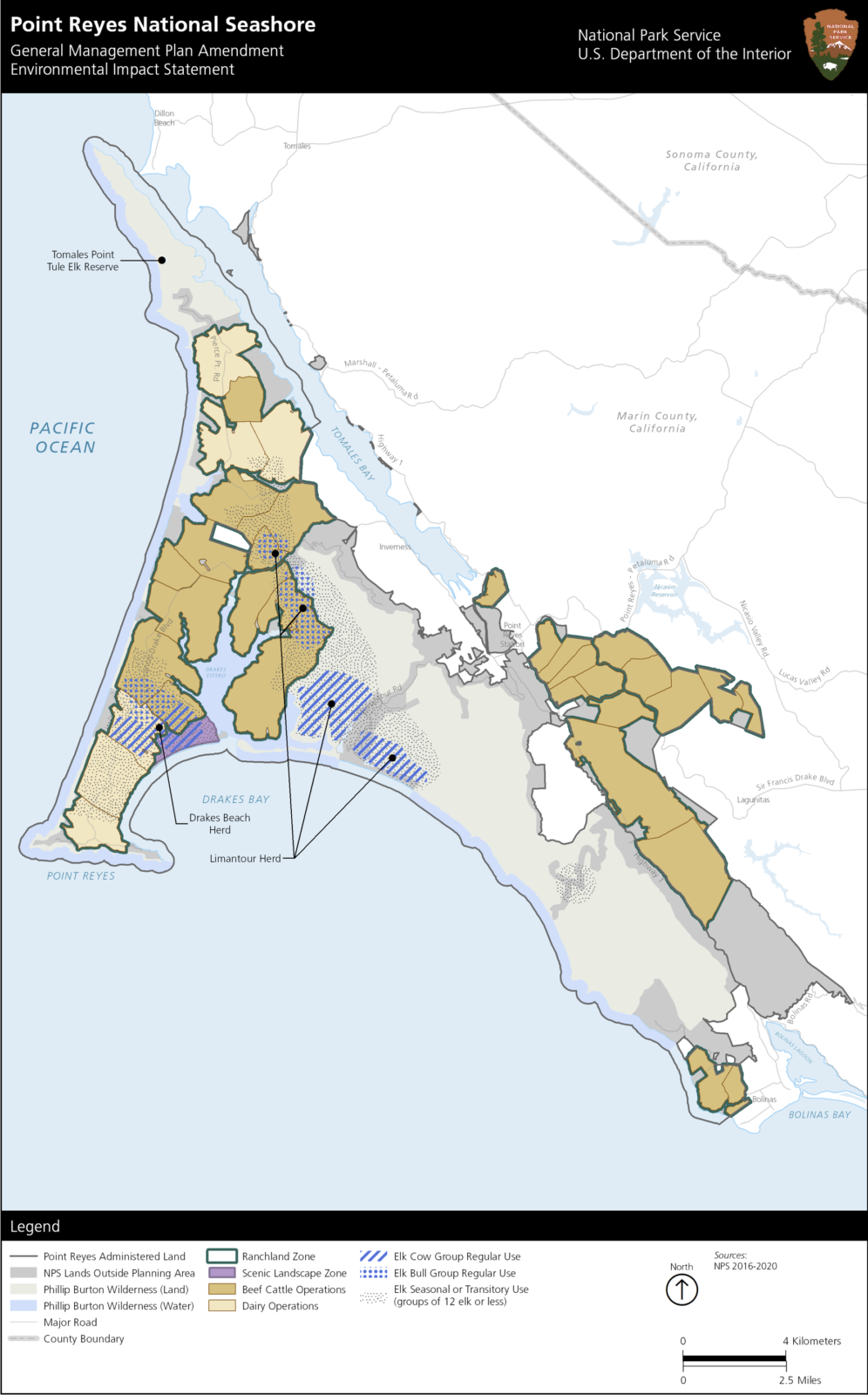

Dairy ranches, beef ranches, tule elk herds, and wilderness area in Point Reyes National Seashore and the northern district of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. (Map courtesy NPS, General Management Plan Amendment Final Environmental Impact Statement, Appendix A)

Today, about 25 percent of the Seashore is pastoral ranchland and nearly 50 percent is federally designated wilderness. But the interconnectedness of ecosystems means that pasture and wilderness areas are never really separate, which complicates the NPS’s efforts to maintain the integrity of both.

Environmentalists have long argued that preserving commercial agriculture shouldn’t be a priority at the Seashore. “Most of them are crappy, weed-infested, overgrazed lots,” said Jeff Miller, a senior conservation advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity, one of the plaintiffs in the 2016 lawsuit. “There’s nothing to celebrate historically or culturally. If people want to see those, there’s tons to see on your way into the park in Sonoma or Marin. You don’t need a national park to have that experience.”

“If people are interested in that period of history,” Miller added, “they can see [Pierce Ranch],” which ceased operations in the 1970s and now serves as a historic ranch interpretive site on Tomales Point.

The ideological disagreement about the value and purpose of Point Reyes National Seashore has once again come to a head over the new General Management Plan Amendment EIS, which evaluates six possible management options for 18,000 acres of ranches within Point Reyes National Seashore and another 10,000 ranched acres in the adjacent north district of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

NPS has identified one of those options, Alternative B, as its “preferred” plan. Alternative B imposes new conservation measures, grants ranchers new commercial opportunities, and extends leases and permits for up to 20 years, securing the place of animal agriculture at the Seashore into the 2040s.

“This seashore in its formation and in all National Parks have responsibilities to maintain cultural and natural resources,” Lewis said. “Alternative B, it’s that effort to do that, to manage both sets of resources and the objectives and mandates that the Park Service has.”

Miller, however, said Alternative B “is a plan to promote the private interest of two dozen ranching families.” The environmental review, he said, “was a process with a predetermined outcome to give the ranchers everything they asked for and more.”

The 2017 settlement required NPS to explore management options that reduce ranching at the Seashore. Alternative D phases out 7,500 acres of ranchlands, Alternative E phases out all six dairies with the option of switching to beef production, and Alternative F phases out ranching at the Seashore entirely.

Alternative A largely maintains the status quo at the Seashore, and Alternative C is almost identical to Alternative B, differing only in the management of tule elk.

A red tailed hawk perches on a ranch fence at the Seashore. (Photo by Matt Knoth, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Four out of the six alternatives, including NPS’s preferred Alternative B, impose new zoning that aims to reduce the harmful effects of cattle grazing on soil and water quality, according to the EIS.

Under Alternative B, approximately 1,200 acres would be removed from ranching to better protect wetlands, ponds, and streams from agricultural pollution. “I think one of the key things people are worried about is water quality,” Lewis said.

The San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board and Marin Resource Conservation District are involved with water quality improvement projects at the Seashore, and “there are a number of studies around the region showing that improvements are being had” in places where cattle have been excluded from waterways, Lewis said.

The EIS also outlines a set of mandatory federal standards for forage production, cattle waste management, and construction and restoration projects to minimize erosion, soil contamination, water pollution, and impacts on plant and animal species.

Despite these measures, however, the EIS states that continued ranching means that ranching activities will, to some extent, continue to negatively impact the Seashore’s ecosystems. Under Alternative B, ranching-related greenhouse gas emissions at Point Reyes, which account for roughly 6 percent of Marin County’s total emissions according to the EIS, would remain near current levels.

For the Seashore’s plants and animals, grazing has an adverse effect on some species and a beneficial effect on others. “There are some protected and rare species that do well in overgrazed and trampled grasslands—burrowing owls, some wildflowers, red-legged frogs do OK in managed grazelands,” Miller said. “But there are a lot of other species that the impacts are overwhelmingly negative—salmon and steelhead trout, a number of the listed plant species.”

Continued grazing won’t push any threatened or endangered species to extinction, “but that doesn’t mean it won’t have an impact,” Miller said.

Miller also says the EIS assumes that all conservation measures will be implemented fully and exactly, which he doubts will be the case. “Center for Biological Diversity did a Freedom of Information Act request about lease violations and the enforcement of leases. They said ‘we have nothing for you,’ which we found odd because we [previously] submitted information on lease violations,” Miller said. “There’s a number of lease violations that people had reported and [NPS] has never once taken any enforcement action.”

A tule elk bull stands in the Tule Elk Reserve on Tomales Point. Currently, about 13 percent of California’s 5,700 tule elk live at Point Reyes. (Photo by Matt Knoth, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Seashore’s responsibilities to protect both ranches and wildlife are perhaps most at odds when it comes to growing tule elk herds that venture onto leased ranchlands, competing with cows for forage and damaging ranch infrastructure.

An endemic California species that has rebounded from the brink of extinction, tule elk are symbols of the Seashore’s rare wildlife. They were abundant in the area for thousands of years under Coast Miwok stewardship, but by the end of the Gold Rush, agriculture, logging, and overhunting had extirpated tule elk from the peninsula.

The NPS established a Tule Elk Reserve in 1978 where the elk flourished, and in 1999, several individuals were moved to a wilderness area near Limantour Beach to establish a free-roaming herd that would boost the population’s genetic diversity. Shortly after, some of those elk established a second free-roaming herd near Drakes Beach. This herd, which now consists of around 138 elk, has been troublesome for nearby ranches.

Alternative B proposes killing 12 to 18 tule elk per year to keep the Drakes Beach population capped at 120 individuals. Any elk that try to establish new herds, including a group of two dozen tule elk that seem to be breaking off from the Limantour herd, would also likely be shot. NPS would hire professional hunters to do the culls, as the EIS concludes that allowing hunting within the Seashore would be too dangerous.

“The National Park Service, of all agencies, is going to start shooting the most iconic wildlife in the park to appease commercial lease holders,” Miller said. “It’s completely nonsensical.”

Other methods of keeping the elk off ranchland, like hazing and fence repair, don’t seem to work. The NPS has considered contraception and surgical sterilization to manage the elk population, but those methods were deemed too difficult to implement. Elk relocation is also not currently an option because the California Department of Fish and Wildlife wants to prevent the spread of Johne’s disease, a disease common to dairy cows that has been found in Point Reyes elk.

Dennis said she’s sympathetic to the emotional nature of killing wildlife, but that elk are managed in a similar fashion elsewhere in the state. “Nobody’s getting up in arms that the state allows hunters to come in and shoot the elk, but they do get upset that the NPS would do a very selective take in order to minimize the effect on ranchers that are most impacted,” she said. “They’re wild animals, but they’re in a confined area. We can’t just let elk run wild in California anymore.”

Alternatives A and E would continue non-lethal management of the free-roaming tule elk herd, and Alternative F, which ends ranching, would allow all elk, including those currently confined to the Tule Elk Reserve, to roam freely throughout the Seashore. However, the EIS notes that because no natural predators, except for the occasional mountain lion, exist in Point Reyes, population control methods would eventually be necessary to prevent overpopulation.

The Seashore’s ranches also play a role in the local economy. David Lewis said that the ranches “contribute about 17 percent of the acreage and production value of Marin’s working lands.” The EIS calculates that discontinuing ranching would cost the region 63 jobs and $16 million in annual revenue, plus indirect losses for veterinary services, feed delivery, and other support services that rely on a critical mass of agriculture in the community. Multi-generational ranches at the Seashore are “part of the fabric” of rural Marin County, Lewis said.

Alternative B allows ranchers to diversify their operations, which Dennis said “is a practical acknowledgement that the ranches are operated now in a contemporary time. The ranchers need to have some economic diversification in order to meet market demand.”

Diversification would be confined to certain ranch areas and negotiated on an individual basis, which could include adding chickens, sheep, goats, and/or pigs, 2.5 acres of row crops, ranch tours, farm stays, and small-scale processing and sale of ranch products.

It’s “a really disturbing development,” Miller said. “They have no business in anyone’s private economy or economic viability.” He said that some ranch owners have been very politically active, hiring lobbyists to “bully the Park Service into getting what they want.”

Before the Final EIS was released, a draft was made available for public comment last year in accordance with the National Environmental Protection Act. The Resource Renewal Institute, one of the plaintiffs in the 2016 lawsuit, analyzed the 7,627 submitted comments and found that only 2.3 percent of them supported continued ranching at the Seashore, while 91.4 percent of the comments opposed it.

The report also notes that the comments convey “a strong sense of betrayal and cynicism regarding the perceived misuse of public lands, cruelty to wildlife, allegiance to commerce and politics over commonwealth, and shortsightedness with respect to climate change and endangered species.”

Holly Doremus, a professor of environmental regulation at Berkeley Law, said that amendments to the seashore’s founding legislation “specifically said that ranching and dairying could continue.” To balance its priorities of protecting natural resources, cultural and historic value, and recreational opportunities, the NPS “finds ways to accommodate both their mission and the local political context. And here,” she said, “the enabling legislation gives the Park Service a huge amount of discretion.”

The NPS is now consulting with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Marine Fisheries Service, and the California Coastal Commission about the preferred alternative, said the Seashore’s Outreach Coordinator Melanie Gunn. The NPS anticipates this process will take a few months, she said, and then the regional director, a position temporarily held by Linda Walker, will finalize a General Management Plan Amendment.

“I hope people will take the time to look at those appendices about the conservation efforts and lease agreements, and at the plans for managing the elk herd before assuming its either [cattle] or [elk],” David Lewis said. “Come to your own conclusions about that.”

The 250-page General Management Plan Amendment Final Environmental Impact Statement, as well as the Appendices, are available to read at NPS.gov.

Clarification: this story has been changed to reflect that while the 1962 legislation establishing Point Reyes National Seashore did not mandate or prohibit ranching, later amendments gave the U.S. Secretary of the Interior discretion to allow ranching to continue indefinitely.