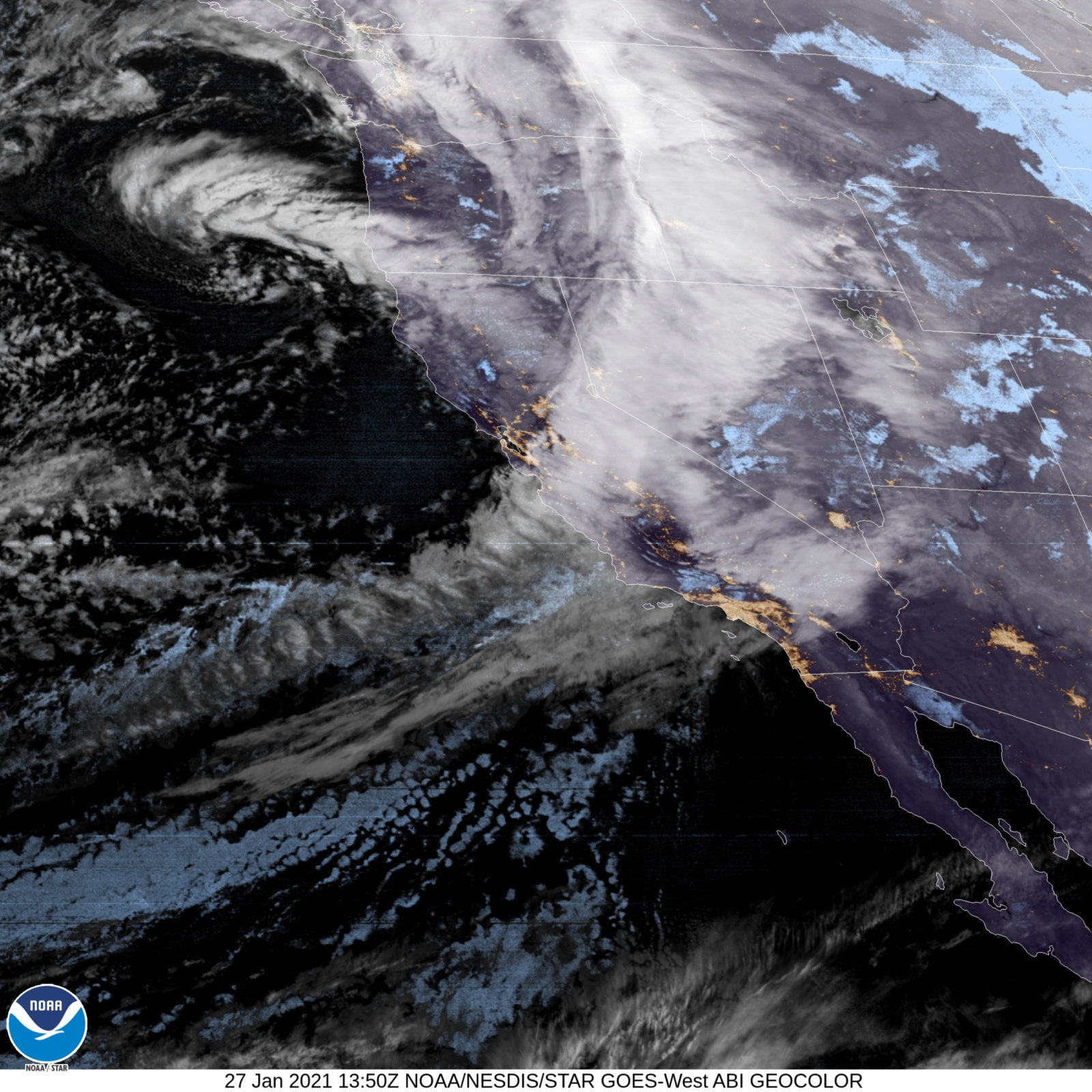

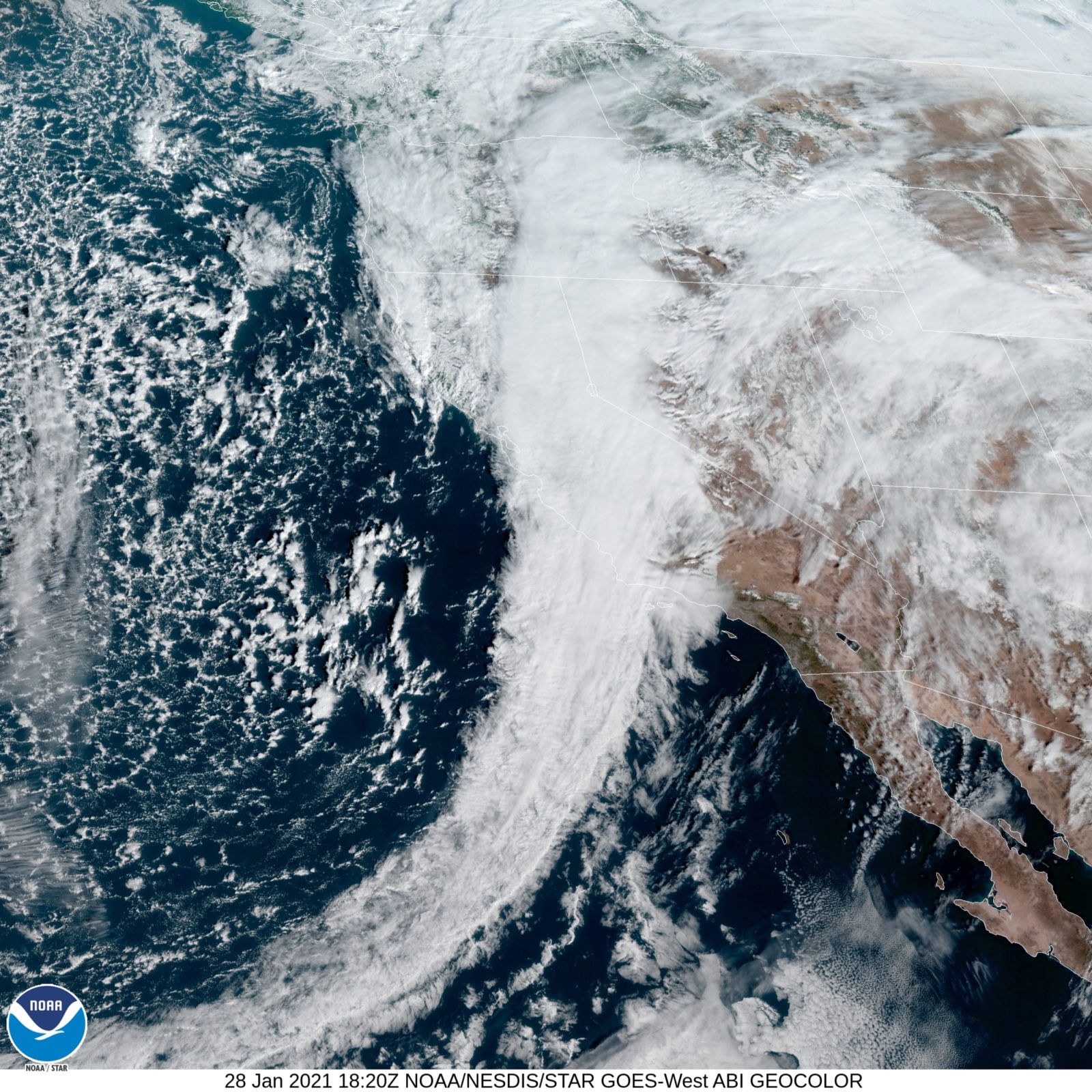

Ten days ago the state set new heat records and brush fires broke out. Burn areas in the Santa Cruz Mountains rekindled. Then, over the last three days, a 2,000-mile-long filament of water in the sky burst over the areas that last week sat brown and smoking. Snow fell on peaks and even some lower hills in the Bay Area. The California Department of Water Resources Central Sierra snow measurement station jumped from 42 percent of average to 62 percent of average.

The Geysers in #SonomaCounty: How it started, January 18, 2021…How its going Jan. 26, 2021. @NorthBayNews @NWSBayArea #CAwx #AtmosphericRiver pic.twitter.com/HLDezePGaK

— Kent Porter (@kentphotos) January 27, 2021

An atmospheric river is a beautiful microcosm of California weather and climate extremes and the narrow edge between dry and wet in the state. With their year-defining implications for water supply, agriculture, and summer fires, these rare events number among the most significant few days of an entire winter. To understand them is to understand in part how Californians will navigate a rapidly warming world.

“It’s been a remarkable year for California climate because of how hot and dry it was,” Stanford graduate student Katerina Gonzales said. “That hot and dry primed the area for these incredibly devastating wildfires. We have burn scars now, all over the area, just sitting there now, hoping that a bunch of rain doesn’t fall out of the sky. … I’ve seen a lot of folks saying, ‘oh my gosh, this is so wild, we had wildfires, now we have atmospheric rivers.’ Just putting that into context, this is what is to come.”

Gonzales studies the ways atmospheric rivers differ from each other, to try to define what drives them and how best to predict their effects. In a paper published in November 2020 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, Gonzales and her collaborators looked at atmospheric rivers in California from 1980-2016 to categorize them into two “flavors,” moisture-dominant and wind-dominant. While she said she can’t tell yet what flavor this week’s atmospheric river had, it’s nonetheless a reminder that there’s more than just water to consider.

“I think it’s a good example of the full range of impacts an atmospheric river can have,” she said. “We’ve seen a lot of precipitation, which we expect. But also high wind gusts. Trees being knocked down, and power outages across the Bay Area. These are impacts that we don’t always think about with atmospheric rivers.”

Much of the scientific literature on atmospheric rivers is based on the United States West Coast, but scientists increasingly recognize that atmospheric rivers carry much more than just water around the world, says NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory chief scientist Duane Waliser. In a study published in 2018 in Nature Geosciences, Waliser and UCLA earth scientist Bin Guan looked at 15 years of extreme wind events in Europe and found that 14 out of 19 were landfalling atmospheric rivers. “Atmospheric rivers are responsible for a lot of the extremes in surface winds that occur along the coast,” Waliser said.

In a separate 2018 study first-authored by UC Merced postdoctoral researcher Vicky Espinoza and led by Waliser, researchers showed that the total number of atmospheric rivers will likely decrease as the climate warms, but individual atmospheric rivers are more likely to be larger and more intense. Waliser offered a speculative explanation for a decrease in overall atmospheric rivers: the poles are warming faster than the tropics, reducing the strength of atmospheric waves generated by the temperature difference between the two. Those waves drive atmospheric rivers; as the waves become less frequent so do the atmospheric rivers.

“It feels right, because of that feature, that we can get less atmospheric river events,” Waliser said. “But yet, any given one of them is longer and wider and that ends up accounting for a person on the ground seems to experience atmospheric river conditions more often.”

With less frequent events, though, the difference between extremely wet and extremely dry becomes even narrower. After a summer and fall characterized by record-setting fires, and a winter characterized so far by extreme dryness, it’s natural for Californians to increasingly see winter storms through the lens of what they’ll mean for the summer to come. Sol Kim, a graduate student climate scientist at UC Berkeley, says he’s increasingly aware of the ways researchers think about fire and water acting together in tandem.

“While California has had to deal with that in this climate before, it’s becoming a lot more of an issue in terms of human safety,” Kim said. “In particular with this storm, people are concerned with the record burn areas throughout California that might turn into debris flow. But even in a wet year, an atmospheric river might provide the precipitation to grow more vegetation, which if followed by a dry year could lead to more fires.”

Kim researches the different ways that atmospheric rivers originate in the Northern Pacific Ocean. He said he was struck by how cold this storm was. “Thinking about future trends for California atmospheric rivers we’re seeing a warming trend within storms in the future,” he said. “This storm, if it didn’t have all the cold air mass behind it, it could easily have been a lot more precipitation falling as rain. Of course that leads to a lot of water management problems and public health issues.”

Researchers have called California’s increasing swings between wet and dry years, and even wet and dry periods within the year, “precipitation whiplash.” The last three days are a reminder, Gonzales says, of what we face now and in the future.

“Not only do we have climate whiplash, but most of those punctuations are going to be in a very small window,” she said. “We might have 75 degree days in January and small brushfires. Not only that but it’s going to intensify with the path that we’re on. What I would say is that the public, infrastructure agencies, city county state level government, we need to make real investments in plans, and soon. This isn’t just when climate change comes in 25 years. We’re living in it!”