The main draw of Sobrante Ridge Botanic Regional Preserve is the pallid manzanita (also known as Alameda manzanita), a California endangered plant species that only grows in the East Bay, and primarily at Sobrante Ridge and Huckleberry Botanic Regional Preserve. The distinctive smooth red bark of the manzanitas shines in the dappled sunlight, and the manzanita grove overlooks the San Pablo Bay as well as the housing developments in the El Sobrante valley.

I had gone to Sobrante Ridge looking for the rare manzanita as a distraction from the pandemic, but instead found myself drawn to a short paragraph on the park’s brochure about vaccines. It said that the land that was now the park used to be owned by Cutter labs in Berkeley, and that they used blood from large animals to produce vaccines. Rather than finding refuge from the pandemic in East Bay Parks, I found myself sucked into the story of Cutter Ranch, and discovered how Sobrante Ridge influenced the history of vaccines.

Dr. Frank Santos was born on the Cutter Ranch in 1938. His father, Frank Santos Sr., the eldest of nine children, was orphaned in 1918 when his mother died of the Spanish flu. Becoming the family patriarch at the age of 17, Santos Sr. turned to dryland farming on land he leased in the Livermore Valley. Working with horses to plow his fields, he became recognized locally as a horseman, and as his son told me, “accumulated the knowledge that made him so valuable to Cutter lab.”

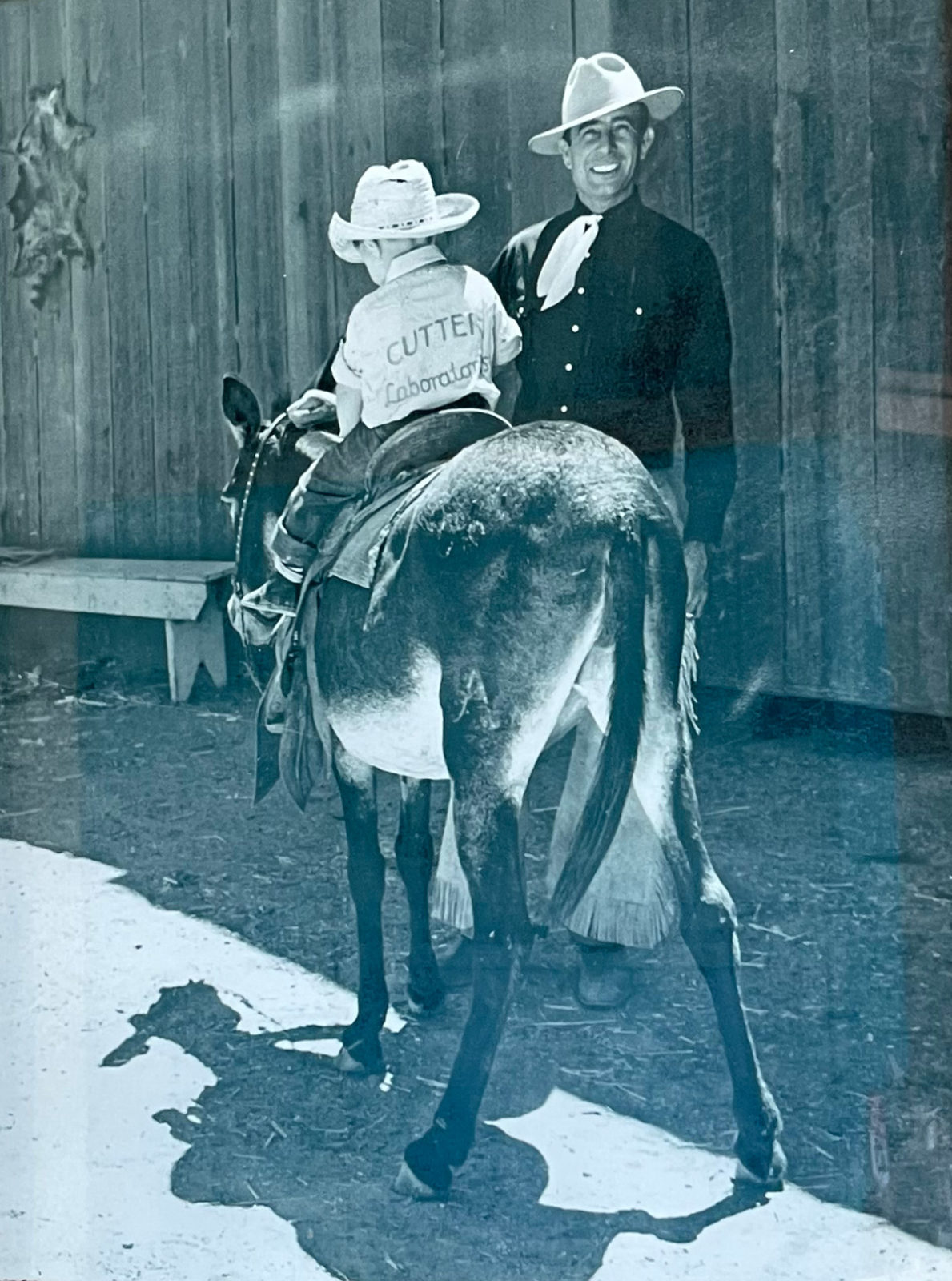

The Santos family moved to the Cutter Ranch in 1936 to manage the company’s growing operation, and Frank Jr. was born two years later. He fondly remembers his childhood at the ranch, from the nearby orchard where he’d pick apricots on horseback to the hogs that the family would raise and send to a German butcher to cure for them. He remembers the outings that the Cutter family would have to the ranch, at one point inviting the entire cast of the production of Oklahoma! for an afternoon barbecue. On other occasions, the Cutter family and company employees would come out to watch the three boys, Don, Russ, and Frank, show off their roping skills in an arena the company built. (Later, both Russ and Frank would have careers in rodeo, which Frank used to finance his veterinary school at UC Davis. The Santos family was inducted into the California Rodeo Hall of Fame in 2014.).

In the 1930s and 1940s, the Cutter Ranch was one in a string of ranches along what is now Castro Ranch road, on the southern edge of the small town of El Sobrante, whose name translates to the “leftovers,” since the El Sobrante filled in between other Spanish land grants.

The Cutter Ranch in El Sobrante was an extension of Cutter Laboratories’ operations in Berkeley. Founded in 1897, the lab bought a block for its production and research divisions in West Berkeley in 1903. Cutter Labs initially kept guinea pigs, mice, rats, pigeons, chickens, rabbits, sheep, goats, horses and cattle at a barn at the Berkeley facilities. The barnyard smells and sounds irked their neighbors, who complained at City Council meetings. The ranch offered a solution to this problem, offering space to store the animals they needed for veterinary vaccines and other materials they made. At the time, Cutter was a leader in veterinary vaccine production, producing popular and effective vaccines for common diseases like hog cholera, anthrax, and blackleg.

Much of Cutter’s early success came from improving veterinary vaccines already on the market. For example, the anthrax vaccine, which was already provided for free to ranchers by the government, was notoriously variable because of its production process, and required ranchers to round up their cattle twice to administer it. In contrast, the Cutter vaccine inoculated cattle just once with both an anthrax spore and a serum that came from cows who had already been administered the vaccine. As a result, cows not only had better protection against anthrax, but ranchers were able to expand into swampy areas where anthrax was rampant, like Los Banos, California, and swamps in Louisiana.

In the 1920s, Cutter expanded from veterinary vaccines to treatments for humans. Drawing on their expertise and animal testing, Cutter used animals to produce the materials that they sold. In the early 1920s, the lab’s most important products were diphtheria and tetanus antitoxins that were used as treatment. At the time, diphtheria was one of the leading causes of death in children. The antitoxins came from horses. Cutter Labs would inoculate horses with small doses of the disease, eventually increasing their tolerance until the horses had high concentrations of the antitoxins. Then, the lab — or Frank Santos Sr, as ranch manager — would bleed the horses, and this blood would be processed and sent to hospitals to treat patients.

These serum horses, as Dr. Santos (Jr) called them, were largely considered disposable by the company, only useful inasmuch as they provided the blood the company needed for antitoxins. The lab got them from farms where the owners were switching to tractors, which rendered many working horses obsolete. The horses were sent by the trainload from places like Modoc County to the ranch in El Sobrante, where they would stay along with the cattle, hogs, and chickens that the Santos family kept. Within only a two decade span, however, the Cutter Ranch would become, as Dr. Santos put it, “outdated.”

By the late 1940s, the antitoxin serums that Cutter produced were no longer needed at hospitals. In 1948, the diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTP) vaccine, which did not require as many large animals to produce, became standard, and cases of these diseases dropped. The surge in vaccine production in the 1950s also became what was known as the downfall of Cutter labs: the Cutter incident.

After the polio vaccine was licensed in 1955, the government told seven laboratories across the country to start producing the vaccine following Jonas Salk’s methods, and Cutter was the first to complete production. Cutter’s polio vaccine followed federal regulations but did not properly inactivate the virus, leaving activated viruses in the vaccine. The vaccinations caused more than 40,000 cases of polio, leaving 200 children with varying stages of paralysis and killing 10 before it was recalled, as physician Paul Offit describes in his book The Cutter Incident.

Today, the Cutter Incident is primarily remembered as a cautionary tale against rushing into vaccine production. Accounts of the Incident detail the importance of testing and safety in clinical trials, and argue that events like the Cutter Incident help explain vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccination movements today. While the social effects of the Cutter Incident are today largely forgotten, the Incident had enormous downstream effects on how companies produce vaccines today.

After the Cutter Incident, Cutter was sued and found to be liable for what their faulty vaccine caused, and eventually settled cases for $3 million. The Cutter Incident was not only bad publicity for Cutter labs, but the court case set a legal precedent in liability without negligence. Under this standard, companies could be found liable for damage their vaccines caused even if they followed the guidelines set by the Food and Drug Administration. Offit argues that this caused legal precedents that “ironically… caused pharmaceutical companies to abandon existing vaccines and to reduce their efforts to develop new ones.” As a result of both liability and financial cost of vaccines after the Cutter Incident, vaccines became high-risk and low-reward for pharmaceuticals. By 2003, only 1.5 percent of global pharmaceutical sales were vaccines. Harvard postdoctoral fellow Nathaniel Moir, analyzing the Cutter case in the context of COVID-19, argues that vaccines would likely never be produced without government intervention.

After the Cutter Incident, companies turned to other more profitable and less risky ventures — like pain medication and bug spray, for Cutter Labs — that would replace the role that vaccines had once played. Land became a less important part of Cutter’s business. Fred Cutter, one of the three sons of the founder and then vice president of the company, said that they no longer needed to raise horses to produce various serums, since new uses of developing treatments were just as effective and less land intensive.

In 1956, Cutter began to try to sell off the ranch, and an Oakland Tribune article reported that it would sell 416 acres of its land in El Sobrante adjacent to Castro Ranch as part of a larger housing development. At the time, speculation for land in El Sobrante was flourishing, as the I-80 freeway was under construction and the cities of Richmond and San Pablo fought over the rights to annex portions of unincorporated El Sobrante in order to gain the tax revenue of new housing and freeway-related housing developments. Even as the sale failed, suburbanization was reaching the hills near Cutter Ranch.

After Frank Santos Sr. died in 1959, Lucille and her son Don stayed on the ranch, with Don as manager. Eventually, both she and Don moved off the property, with Don managing it from afar. In 1980, Cutter Labs, now under the ownership of Bayer, sold the 416 acres of ranch for $1.65 million to Damé Construction Company. The appraiser noted that the property included “rolling hill land, barns, and old house of no value.”

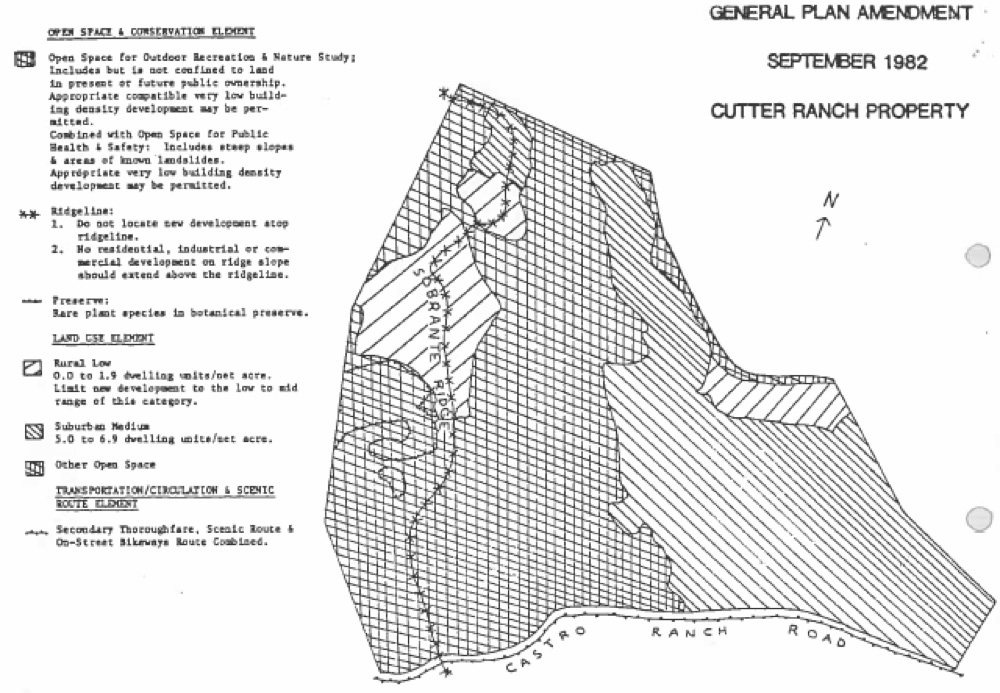

Damé’s initial proposal had been to build 514 homes, with 440 on the flatlands and 74 on top of the ridgeline. The company annexed the development into the boundaries of Richmond with the hopes that the medium high home values would provide revenue to the city, which had lost money as a result of Proposition 13’s limits on property tax revenues. The city of Pinole opposed the proposed development on top of the ridgeline, which would be visible from Pinole and increase traffic.

The proposed ridgeline development also threatened the pallid manzanita, said Neil Havlick, who had worked on the acquisition for East Bay Regional Parks District. A botanist by training, Havlick was sent to a Richmond City Council meeting to comment on the value of the plant. He told me that he was afterward confronted by a “very angry” Carl Damé, who told him that “he was going to get even” with Havlick by calling his supervisor. Havlick was surprised when Damé later did the “gracious thing” of abandoning the ridgetop development, and was happy that the new 277 acre park was larger than what he had initially imagined to save the 20 acres of manzanitas alone. A later summary of the acquisition framed the compromise this way: “The westerly more hill portion was reserved for open space or park use, in order to pacify adjacent residents and get subdivision approval.”

On the documents finalizing the real estate plans in the 1980s, the name Cutter Ranch appears frequently to describe the parcel and label the area. But today, the traces of Cutter Ranch are harder and harder to find except in these documents. No cows graze the hills, and the Carriage Hills subdivision sits on top of what used to be the ranch.

When I visited the park a couple of weeks ago, I went to try to find the traces of the ranch. The old barns have been replaced by sub developments, but halfway down an old road leading to a powerline tower, I found a small bit of evidence—an old barbed wire fence in disrepair, of the right age and location that would have made it part of a far end of a pasture. In many ways, it was just a fence in disrepair, like hundreds I had seen throughout California marking old properties and pastures. Yet, on that day it seemed much more extraordinary as I thought about the vaccines that were on everyone’s minds, and the pandemic that had caused me to start visiting new parks in the first place. Rather than the escape that I had hoped to find in a local park, I instead found a forgotten story of how vaccines were made.