When thick brown clouds of smoke settled into the sky above Point Reyes National Seashore in fall 2020, the artist Tom Killion began packing his car with framed prints he’d made over the past four decades, along with thousands of sketches from a lifetime of hiking through California and the West Coast.

For the past four decades, Killion has worked as a printmaker, focusing almost exclusively on scenes from the rugged Northern California coastline and the high Sierra. “Tom is a natural artist,” said his longtime friend and book artist Peter Thomas. “All along it has been clear that his images are very compelling.”

The last time Point Reyes burned, in 1995, Killion was living in Santa Cruz, but came up to help a neighbor evacuate. Together they moved valuable arts and craft style furniture and collectibles out of the house and onto a marshy field along Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, preparing for the worst. Later that night, Killion hiked across Tomales Bay with his camera and a small sketchpad. Around two in the morning, Killion stood on Olema Hill facing the inferno tearing across Bolinas Ridge, and watched it go out to sea.

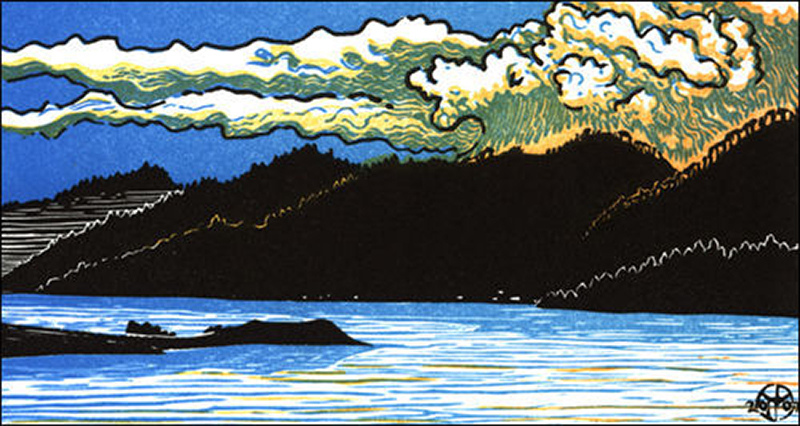

Years later, in 2007, Killion carved a tiny print from that scene. Just four by seven inches, the compact image depicts defined plumes of smoke drifting across the black silhouette of Bolinas Ridge. The scene is calm: the fire’s menacing bite appears contained in neat swirls dissipating into sea and sky. The incredible destruction is rendered as benign beauty.

Killion’s prints are known for their defined lines and psychedelic tints, which accentuate the vivid colors of California landscapes. Killion will often spend months working on a single print, re-carving the key block and isolating sections that will be inked in different colors. The end result is an arresting composition of electric colors and intricate botanic and topographic detail — a result that’s immediately recognizable to anyone who’s hiked through the iconic trails of Northern California.

Killion’s prints have become a metonym for Northern California landscape art, after years of cultivating a loyal following and publishing several books with Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gary Snyder. After publishing numerous books that he illustrated, Killion turned to making prints as artwork. He prints a handful of different works in editions of about 180 every year, and his work has been featured in galleries throughout California, including Bookshop Santa Cruz and Leona’s in Point Reyes Station.

But his appeal goes far beyond the white-walled gallery space. Tanya Egloff, a long time Killion fan, can vividly remember the first time she encountered a Killion: she had just moved to the Bay Area and was walking through the Ferry Building in San Francisco’s Embarcadero when she saw a pack of greeting cards with images of the mountainous terrain along the Pacific Coast Trail.

“His images just talked to me — it’s what I love about California: the wild natural beauty and the accessibility of it,” she told me. She framed one of the cards and has brought it with her on every move in the last 20 years. As she became more familiar with his work, Egloff came across a mini documentary about Killion’s process produced by PBS in which he described his love for California as “topophilia,” or an immense appreciation for the diverse landscape of California.

“When he said that, I got a real connection to the heart of his work because I feel that way, too,” Egloff told me. “I’ve never heard anybody else express that. It gives me a shared sense of a deep love for the natural environment.” She’s one of hundreds of fans who’ve reached out to Killion to request permission to use his images as tattoos.

Killion’s landscapes reveal an aspirational relationship between humans and nature: the natural environment is intact and wild with human traces reduced to an innocuous trail. The absence of people isn’t meant to remove humans from this environment, but to respect the transcendent beauty of the landscape, emphasizing “the smallness of the human element, where people, paths, boats, and houses [are] dwarfed by the immensity of the natural world,” as he describes it.

After the 2020 Woodward Fire in Point Reyes, when the evacuation order lifted and Killion returned to Inverness, the October heat and smoke persisted. The park’s interior burned for another month, leaving behind the charred, scraggly remains of coyote brush and parched earth. But it gutted the landscape that Killion had spent years recording. Even as winter months returned some green to the hills and the debris was cleared from a few trails, there remains a visceral sense that the landscape is fragile. Longstanding droughts and yearly raging fires have made it less intact. Killion’s longtime friend and Director of California State Parks, Armando Quintero, sees Killion’s prints as baseline data. “It’s a place from which we can measure if we’re advancing, or if we’re losing ground, literally,” Quintero told me.

For Killion, printmaking is about preservation — both the natural likeness of a place and the possibility that humans can live in the world without damaging it to the extent we do now.

“Art is a way you can control the uncontrollable because you can make a picture of the world you want to inhabit,” he said. “Instead of putting an icon of the Virgin Mary and the baby on their wall, today people put a picture of a tree and a mountain. That’s what they want to contemplate.”

His prints provide a glimmer of hope for people experiencing what philosopher Glenn Albrecht has called “solastalgia”: a neologism that combines nostalgia, solace, and desolation to describe the profound sense of loss and isolation experienced when a place one loves is under assault. Killion’s prints are a tangible way to relieve the destabilizing sorrow we feel from losing our collective natural heritage.

When I met Killion at his studio in Inverness in late October, where he showed me a carving in progress of a view of Black Mountain from Inverness Ridge, which is just a few miles from his house. The studio was rudimentary and elegant with exposed beams and an unfinished concrete floor; you could imagine it doubling as a yoga retreat for nomadic techies in search of Californian bohemia.

In one corner, Killion keeps piles of sketchbooks amassed from decades of hiking: thousands of pages scribbled with quick impressions and detailed notes about the lighting, color, and texture of the spot, along with the location and date.

When he begins a new project, Killion selects a sketch based on both its thoroughness and the emotional response the sketch elicits from him, referencing the annotations in the margins. He then composes an image that synthesizes multiple perspectives, perhaps adding a tree or some lupines he encountered earlier on the trail, or combining parts of several different sketches from the same area. While the resulting image isn’t accurate in a documentary sense — there’s no vantage from which you can see all the elements in a single print — it captures what Killion calls “a walking spirit”: a palimpsest of moments observed along the way.

“As you walked through that landscape, you would have seen all these things, and they’d all be in your mind sort of simultaneously,” Killion said. “The print gives that feeling of being in the place, and moving through it.”

Killion’s meticulous process inflects a distinct aesthetic quality that he calls faux Ukiyo-ë, or his interpretation of traditional Japanese wood cut prints. Because he uses a printing press, unlike the strict Ukiyo-ë method, Killion can layer colors, achieving gradient and halo effects of a sunset and shaded hill, for example. The sharp lines from the key block guide the eye towards accentuated detail, like the curve of an incoming tide as it collides with the shore, or the shadow cast by an iris in midday sun. It draws your attention to the banal details that expose the sophistication of natural forms. His prints remind you what it feels like to marvel.

“Beauty leads us to knowledge and understanding and to a relationship with the world. If anything is going to save us, it’s not science; it’s beauty, it’s art,” wrote Malcolm Margolin, the founder of Heyday Books, which has published several books of Killion’s. “I think it’s the love of beauty that has created the National Park System. And I think that Tom Killion is a part of that lineage.”

In a California where fires have made large parts of the state unlivable, where drought has parched the earth for more than a decade, and where record temperatures are set every year, Killion’s portraits of beauty show us what we stand to lose.

“To me, doing landscape is about seeing wholeness in the world,” Killion said. “And on a personal level, it’s a way of kind of asserting some control over the uncontrollable. It makes me feel better, to create in a little square, a little vision of the way the world is when it’s beautiful.”

“To me, doing landscape is about seeing wholeness in the world. And on a personal level, it’s a way of kind of asserting some control over the uncontrollable. It makes me feel better, to create in a little square, a little vision of the way the world is when it’s beautiful.”

Killion, who’s in his late 60s, grew up in Marin County and started sketching from a young age. Before elite cyclists and Teslas dominated the roads of this San Francisco commuter burb, Mill Valley was a rural enclave of military families and beatnik artists.

When he was eight, Killion spent hours drawing fir trees and birds, often in remarkable botanical detail. His mother’s friend, an artist, encouraged him. Around that time, his mother took him to an exhibit of Chinese landscape scrolls at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. Killion was captivated by the tiny scenes: rivers winding through misty canyons and teahouses perched on mountains. “I remember I was interested in it because it looked like Mill Valley, with the mist and the fog and the redwood trees,” Killion said. “It reminded me of where I lived.”

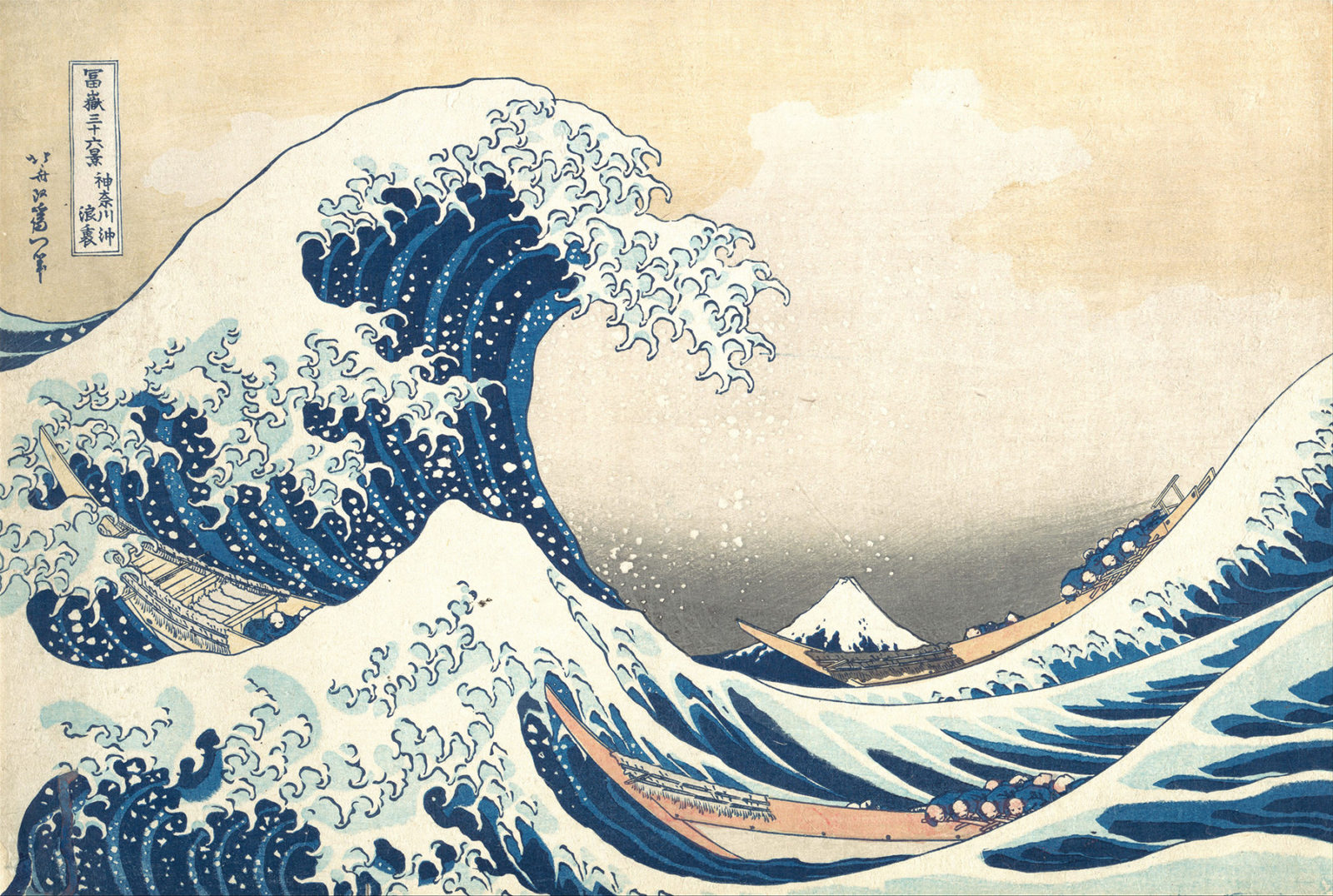

After the museum visit, Killion went to his local art store and picked up a small kit with a few Sumi brushes and an ink stone so that he could try his hand at Japanese-style landscapes. His early technique was improvisational but effective: with ink and color wash, he drew landscapes with defined lines and subtle coloring similar to the museum scrolls. Some years later, his mom gifted him a pocket-sized book of Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mount Fuji, which includes the iconic “Great Wave off Kanagawa” print.

“It was just a little book, but it had one page with each picture of that series and some little poem facing it. That changed my life, that little book,” he said. Hokusai’s ability to depict the subtle seasonal and ambient qualities — decaying leaves and plumes of smoke — around Mount Fuji gave Killion a new visual vocabulary to depict nearby Mount Tamalpais, as it, too, was decorated in seasonal change. These images stayed with him until his college years, when he completed a series called 28 Views of Mt. Tam.

When Killion reached high school in 1967, his mother, thinking about college, insisted he take an entrance exam for an all-boys private high school in San Francisco. The school was meant for boys to become skilled draftsmen or architects, so he started his year with shop classes and drafting where he refined his hand at sketching.

Around that same time, San Francisco was changing from a staid postwar business city to a countercultural center. After school, Killion and his contemporaries, who sometimes wore eclectic outfits from thrifted Edwardian clothes, would watch light shows accompanying concerts of rock bands at the Avalon Ballroom and Fillmore Auditorium. Killion started collecting the concert handbills, intrigued by the retro Art Deco character of these psychedelic tinted posters.

This fascination would later become apparent in his multi-layer color relief prints, which filter the natural world through the spectrum of those Haight Ashbury light shows and Fillmore handbills. Along with developing more sophisticated techniques and perhaps the distance of time, these colors lend a utopic quality to his landscapes, akin to the freeing potential of radical social change in San Francisco’s 1968 summer of love.

Over the next few years, Killion continued to draw landscapes with translucent inks, imitating the sparse sansui, or mountain and water, paintings that chronicle the subtle seasonal shifts in Japan. He sold these drawings for $25 apiece at the Mill Valley Art Festival. “I would draw from my imagination, but based on the landscape of Marin County,” said Killion. “They would always have people in them, girls in beautiful clothes, or a couple. It was like I was fantasizing my romantic ideas about the world the way I wanted it to be.” His art had a way of realistically capturing the environment while making it a more inviting and softer place.

While studying history at UC Santa Cruz, Killion started experimenting with print making, opening up an entirely new medium for his practice. It wasn’t until Killion graduated and broke his leg in a biking accident and was confined to staying in one place that he completed the prints that became 28 Views of Mt Tam. Inspired by Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mt Fuji, these early prints are minimalist compared to his later works, often small and monochrome. 28 Views of Mt Tam was well received by Killion’s growing local audience, and he put the funds from book sales towards a printing press and a permanent studio space he rented for $50 a month. His professional art practice was becoming more formalized.

After graduating, Killion embarked on a world tour that landed him in Europe and Africa, which included free-wheeling adventures like hitchhiking across the Sahara Desert in a Dodge Powerwagon with a couple of French travelers. He was world-curious and his American passport was his ticket.

When he returned to California, Killion began a PhD program in African history at Stanford University, writing his dissertation on labor movements in Ethiopia. Returning to Africa for fieldwork, Killion worked as administrator of a medical relief program in a camp for Ethiopian refugees in Sudan. During his time in the Horn of Africa, Killion sketched and wrote reflections — part diary-like and part researched — that inspired prints and eventually became a book titled Walls: A Journey Across Three Continents. Printed on thick paper and bound by him, the book is a memento of his travels and the times.

Back in the states, Killion moved through the academic circuit for a few years, lecturing at a private university on the East Coast and then at San Francisco State University. Eventually, Killion stopped lecturing and pursued art full time. The restrictions of history came to resemble naturalistic painting: just as he painted realistic landscapes with imaginative flair, he wanted to embellish the minutiae of historical storytelling, taking archival facts and telling stories of his own making.

Settling in Marin County with his family, Killion pursued his art with scholarly rigor, learning about traditional Japanese print making techniques and experimenting with different effects to create and hone his signature style.

In the mid 2000s, California Parks Director Armando Quintero, then chair of the Sequoia Parks Foundation, invited a group of artists, writers, and cartographers to create a collection of work about the American West that reflected contemporary themes of climate change and equity. Along with Killion, Quintero brought artists like photographer David Liitschwagger, poet Gary Snyder, and science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson. The residency, which he named Artists in the Back Country, took place over ten days in the High Sierra. Invited artists spent their days hiking through the mountains and ended them with drawn-out meals and wine and swapping anecdotes about the relevancy of wilderness and parks.

At that point, Killion and Quintero were unacquainted with each other, though Quintero had long admired Killion’s work, which he saw as following in the tradition of early paintings commissioned by the U.S. Congress and the U.S. Geological Survey in the 1870s — especially those by Thomas Hill and Thomas Moran.

Looking at Hill’s View of Yosemite Valley, there is a striking familiarity to Killion’s pastel washed prints of the High Sierra. Painting and sketching en plein air, both artists depict the abrupt bluffs of high altitude rocks in a scintillating spectrum of light, capturing the irreplaceable colors of the western setting sun. The scale of both works of art makes impressive trees look like matchsticks and the towering rocky cliffs impenetrable and transcendental: they possess a beauty beyond any human accomplishment imaginable — a humbling perspective on our insignificance in the natural world.

Both then and now, the landscape continues to be a subject artists turn to when contemplating the ways we relate to the places where we live and the impact we as humans have on the land. Killion’s prints — so imbued with wholeness and beauty — tether us to a collective accountability of how we should engage with these natural spaces.

“For me, landscape art is about loving the world,” Killion says. “It’s about loving a place: all of the vegetation, and the animals, and the landforms, and the waters. Why not understand the joy and its wholeness?”