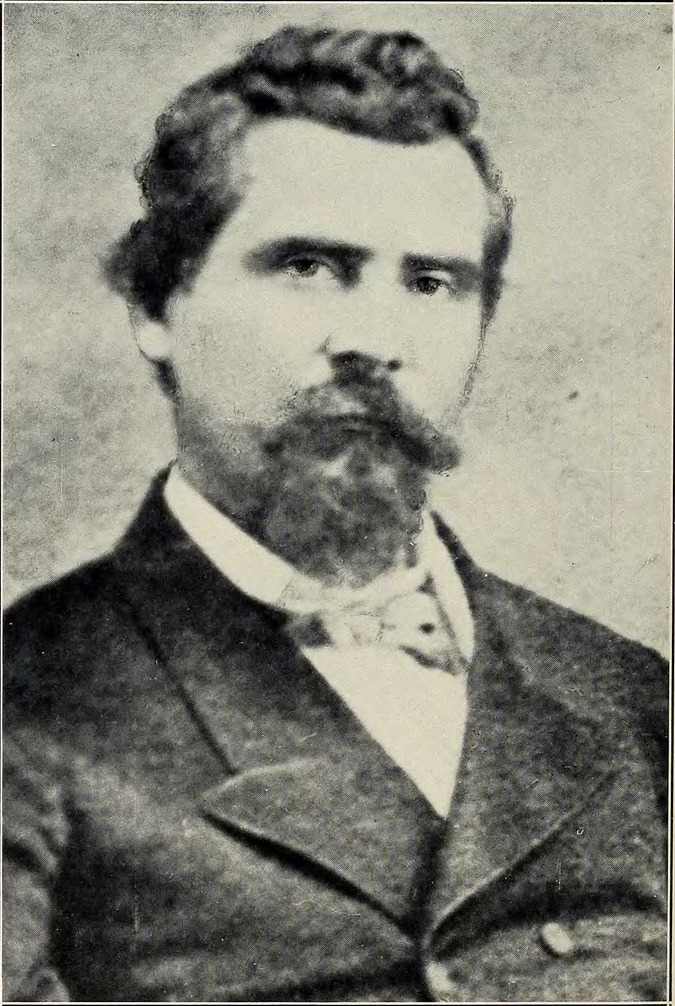

In 1849, a 23-year-old biracial Cherokee man named John Rollin Ridge shot and killed a neighbor in a dispute over a horse. Rather than face a trial, and desperate for money, Ridge fled his home in Arkansas and followed the Gold Rush to the hills of Northern California.

Ridge quickly gave up on hunting gold, because he’d found another profession that suited him better: writing. A talented poet, journalist, and author, he became one of the founding editors of the Sacramento Bee. While traveling the new state as a freelance correspondent he followed newspaper accounts of a series of sensational horse thefts and murders in 1852 and 1853, turning them into his first novel, The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta, the Celebrated California Bandit.

Joaquín Murieta, published in 1854, was the first novel published in California, the first novel by a Native American, and a source text for future stories of masked avengers from the original Zorro novel to Batman. Popular from the start, it has given rise to dozens of academic articles, artistic interpretations, and works of outright plagiarism. It inspired “Yo Soy Joaquín,” one of the signature poems of the 1960s Chicano liberation movement. There is a popular “Corrido de Joaquín Murieta.” Chilean poet Pablo Neruda once wrote an opera called Fulgor y Muerte de Joaquín Murieta. In the 1998 Hollywood film Mask of Zorro, actor Antonio Banderas plays Alejandro Murrieta, who becomes Zorro to avenge the murder of his brother Joaquín.

It also seems quite probable, unless you’ve taken a Chicano Studies class, that this is the first you’ve heard of either Joaquín Murieta or John Rollin Ridge. The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta, UC Davis literature professor Hsuan Hsu writes in The Paris Review in 2018, is “one of the most influential and invisible novels in American literature.”

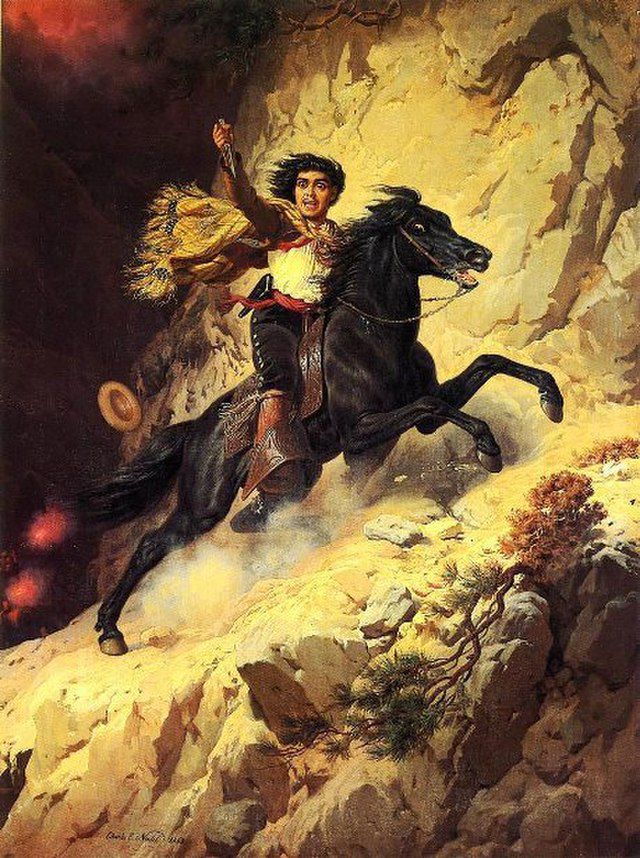

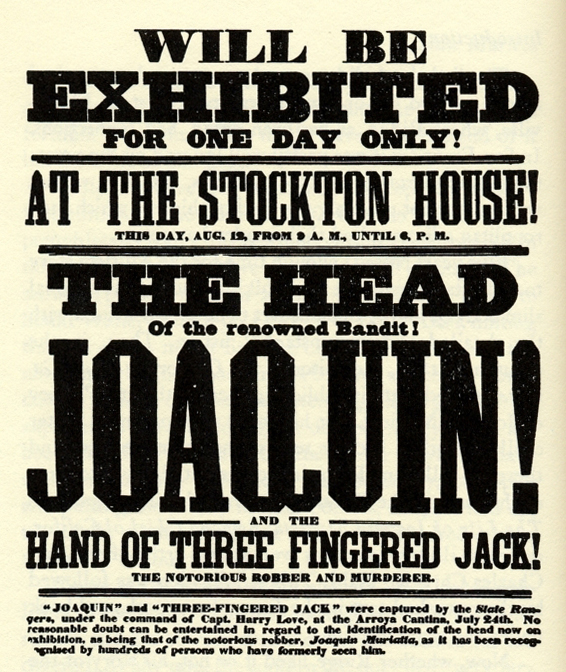

Joaquín Murieta purports to be the true biography of a Sonoran immigrant gold miner named Joaquín Murieta who, after racist American miners rape his wife, steal his land and murder his brother, turns to revenge. Leading a gang of thousands, Murieta rides the rugged spine of the new state of California in a vigilante uprising. He steals from the wealthy, while acting kindly and honorably — sometimes — toward the weak. He provokes white miners and local politicians, taunts them, and rides off in a dash of bravado and horsemanship. While visiting one town incognito he sees a poster offering a $5,000 reward for his capture, and scrawls over the poster, “I will offer $10,000. -Joaquín.” Ultimately, paramilitary forces hired by the state government track Murieta to his remote hideout. A shootout ensues, then a chase. Murieta is mortally wounded and dies at the hands of a mercenary ranger named Captain Love. The rangers cut off Murieta’s head and show it in a jar in Sacramento to earn their bounty.

It is easy to see why Ridge connected with the material. In the 1830s, his father and grandfather had led several Cherokee delegations to Washington D.C., and concluded that the Cherokee should cede their tribal land to the United States for money and land elsewhere. When the treaty took effect in 1836, leading ultimately to the forced resettlement of the tribe to Oklahoma, the Cherokee faction that had opposed the treaty blamed the assimilationist Ridges for their suffering. In 1839, a group of assassins dragged Ridge’s father from bed and stabbed him to death in front of his family. A separate group ambushed Ridge’s grandfather and uncle the same day, killing both. The 12-year-old Ridge fled with his mother and grandmother to Arkansas. The neighbor Ridge later killed in the dispute over the horse was part of the rival Cherokee faction, and almost certainly Ridge had revenge in mind.

The character Joaquín Murieta, like John Rollin Ridge himself, wrestles throughout the novel with questions of morality, violence, and belonging. He decries racism against Mexicans, yet silently accepts the slaughter of innocent Chinese miners. He co-exists easily with Native Californians, and sometimes admires them, but calls them simple. He leads a guerrilla operation through the hills and gullies of the California coast range and Sierra foothills, but he drives his stolen horses home to Mexico to await his retirement. Hsu writes that The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta “takes up some of the most complex themes in American literature: cultural assimilation, racist and antiracist violence, the tension between ethical and political action, and — perhaps most centrally — philosophical questions about the legitimacy of state and extralegal violence.”

Ridge, a Native American writing about a Mexican American in a new state attempting to dispossess both, didn’t just have an interest in violence and revenge. He had a story uniquely possible in early California, and a perspective uniquely suited to reveal the prejudices that animated the early days of the state and that persist today.

“The book is remarkably readable and entertaining, despite the Victorian style,” author Diana Gabaldon writes in the foreword to a 2018 paperback edition edited by Hsu. “Ridge is a master of the art of theme and variation, so while every encounter ends the same way (until The End), we still enjoy the ride. If you want to read a little deeper, though, the story offers a window on the real social dynamics — race, culture, and prejudices — of the time, and may offer grounds for reflection on how much things have changed. Or haven’t.”

The themes of The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta number among the most urgent and discussed matters in California and America today, leading to the obvious question: Who is Joaquín Murieta — hero and historical figure alike — “invisible” to? If Ridge’s novel and his hero have lost their way in the annals of history, are either worth surfacing more widely now?

As a boy, ecological consultant Heath Bartosh’s grandmother would tell him stories of Joaquín El Famoso, the “Mexican Robin Hood,” whose buried gold might still be found in the spurs of the inner coast range framing the rural Ventura County towns where Bartosh grew up. For his grandparents, the story of a masked avenger who refused to bow to his white oppressors, who worked hard to earn what he had, made the connection to Joaquín real.

In a 2011 UC Berkeley dissertation on Murrieta’s enduring appeal, literature professor Blake Hausman writes, “Murrieta is distinctly unlike other folk heroes in that he not only represents the common person; he is also a character that the common person can become. … the California icon is unique among the heroic subjects whose stories are sung in Anglo ballads and Mexican corridos because to sing Joaquín Murrieta’s story is to become Joaquín Murrieta.”

In the preface to his own work, John Rollin Ridge describes Murieta as “a soul as full of unconquerable courage as ever belonged to a human being.”

Bartosh’s grandmother, who grew up moving between Ventura and Rosarito, Mexico, worked in the lemon orchards as a young woman. Her husband told stories about hitchhiking to Gilroy to follow the high price of lettuce, before he joined the military. They understood Joaquín’s fight to get by, Bartosh says, and identified with the way he scrapped every day in the face of racist people and institutions. They didn’t teach Bartosh’s mother Spanish, for fear she’d suffer the same indignities they had. But they pointed out landmarks named after Joaquín to their grandson.

Bartosh turned a childhood spent outdoors into a career as an independent botanist. In traversing the state he’s identified stands of some of the rarest plants on Earth, like the Mount Diablo buckwheat, known by a single population of less than 20 individual plants until Bartosh’s discovery in 2016 of a meadow of millions, or the Livermore tarweed, growing only in a single field in Livermore, completely unprotected until Bartosh helped lead a successful petition in 2016 to see it listed as endangered. After a fire burned through Mount Diablo in 2014, Bartosh found fire poppies growing in the burn scar, the first time they’d been seen on the mountain since 1977.

Like many California botanists, Bartosh was drawn early in his career to the inner coast range, a rugged mixing zone down the center of the state where desert flowers bloom within a few miles of altitude-loving incense cedars and rare plants seemingly plucked from the lush forests 200 miles to the north. Central to the possibilities of both the novel and the history, these corrugated landscapes remain some of the wildest places in California. Pull up a modern map of the Diablo Range and look at the names of the places Murieta and his gang traversed: Valle de las Aguilas, Valle de Quien Sabe, Valle de los Muertos. Today you can snake up into those hills, out of cell range for hours, only the wind for company, manzanitas growing 12-feet high over rutted washboard roads. It is a natural setting for one of the great bandit novels in literature. It is also a rocky spine separating some of the fastest-growing flatlands in California, and so a natural setting to consider the state’s future.

Bartosh still remembers the first time he visited Cantua Creek, a trickle of permanent water on the eastern edge of the Diablo Range, where in the novel the final shootout between Murieta and the rangers takes place. It was “magical,” Bartosh says, to stand in the narrow valley, to see the obvious appeal of the place to the outlaw he’d grown up hearing stories about, to connect all those stories to his own present. Yet it puzzled him then, and still puzzles him now, that these ecologically special places and the character who once dominated them are so little known.

“It’s really kind of amazing that somebody that played such an important part in the storytelling fabric of some of California’s descendents, is still kind of lost to the larger public,” Bartosh said. “We hear about the head of a guy in a jar getting toured around California. It doesn’t make the connection as much to this oral history fabric that I think a lot of Chicanos in California are familiar with.”

So what happened? Hsu, the UC Davis literature professor, says the novel has been overlooked in part because of a long history of suppressing the voices of people like its writer and its protagonist.

“It’s also not unusual for popular novels — especially sensationalistic adventure fiction — to be neglected by literary critics, who for much of the twentieth century tended to privilege works that framed themselves as formally complex and engaged with the Western canon,” Hsu wrote in an email. “The novel’s depiction of Murieta as an anticolonial, racial avenger would have made it seem too didactic, too graphic in its violence, or too morally ambivalent to critics interested in morally uplifting fiction.”

In his 2011 dissertation, Hausman further wonders what it means for modern multicultural reading lists that the first Native American novel features a Mexican American main character. For Cherokees, Ridge’s legacy remains complicated, Hausman writes. Ridge’s father signed the treaty that betrayed the Cherokee people to the United States; Ridge, like his father, saw assimilation as inevitable and turned his back on tradition. In Joaquín Murieta he portrays Native Californians as backward and calls them by a slur common at the time. His writings advocate for the oppressed, but he owned Black slaves and opposed both abolition and the Civil War. When he couldn’t raise the money to travel to California, Ridge mortgaged one of his slaves.

Hsu also points out that Ridge’s novel “disturbingly echoes the anti-Chinese sentiments of its time.” Ridge writes the Chinese miners as passive, exoticized, objectified, a direct contrast to the heroic individualist Murieta. In his 2018 Paris Review article Hsu calls Ridge’s ideas about race “complex and often incoherent.”

“Ridge’s deeply troubling political views make it difficult to read his novel as a transparently anti-racist statement,” Hsu wrote in an email. “For students, the tension between Ridge’s anti-racism and his reliance on racist conventions raises important and all-too-timely questions about the difficulties that can stand in the way of cross-racial coalition, and about whether racism can be effectively combated through investments in individualism and assimilation.”

The violence in the novel also offers a window into an essential piece of United States history. Carlos Alonso Nugent, a historian of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands and recent Mellon Fellow at Stanford, says he’s taught Joaquín Murieta alongside a book by Yale historian Ned Blackhawk called Violence Over the Land. Blackhawk argues that violence fundamentally reshaped relationships between almost every group of people living in what’s now the American West, and that historians “have failed to reckon with the violence upon which the continent was built.” Joaquín Murieta captures that violence, some of the many dimensions it takes, and the forces that animate it.

“What we euphemistically call the Gold Rush created this extremely violent transition of people and place that remade the land in ways we’re still dealing with,” Alonso Nugent told me.

Ridge had internalized so much violence in his own life that maybe he was uniquely positioned to describe its effects, too. He lived the arguments and pressures that split the Cherokee Nation. He saw the American West defined by force and who could raise it. In one of his poetry collections, published after his own death, he described his memories of his father’s killing and what it had done to him. “Then succeeded a scene of agony the sight of which might make one regret that the human race had ever been created,” Ridge wrote. “It has darkened my mind with an eternal shadow.

John Rollin Ridge always insisted his sensational crime story was true. Though it is obviously not fully so, historians have debated the percentages ever since.

“If it is difficult to separate the mythical from the historical elements present in all oral or written narratives, the task becomes nearly impossible when one is dealing with a figure like Joaquín Murrieta,” Chicano literature professor and historian Luis Leal, who died in 2010, writes in an introduction to the 1999 edition of Ridge’s novel.

The most determined account of the “real” Joaquín Murrieta comes from an amateur historian named Frank Latta, who was born in 1898 in the Orestimba Creek area east of present-day Henry Coe State Park, and spent 60 years researching the legendary hero, including traveling to Sonora, Mexico to attempt to find and interview Murrieta family members. Latta’s 650-page magnum opus, Joaquín Murrieta and His Horse Gangs, was published in 1980. It’s a thorough read, but not particularly accessible. You have to either drop $350 for the hardcover on Amazon, or head up to the UC Berkeley rare books library to have a white-gloved librarian dig out the university copy.

Latta painstakingly assembles archived newspaper stories to make his case. One account from January 1853 describes murders, robberies and “outrages committed in the lonely gulches and solitary outposts of that region,” and seems to be the first to have a specific bandit to name: “The band is led by a robber, named Joaquin, a very desperate man, who was concerned in the murder of four Americans, sometime ago, at Turnersville.”

Several similar reports follow. Then, according to the records of the California State Legislature, in May 1853 California Governor John Bigler created a mounted militia led by Ranger Harry Love to hunt down what the law called “the party or gang of robbers commanded by the five Joaquins, whose names are Joaquin Muliati, Joaquin Ocomorenia, Joaquin Valenzuela, Joaquin Bottelier and Joaquin Carrillo.”

The newspaper records aren’t clear, but the head going on display in a jar seems to have consolidated attention on the surname Murrieta. A much-reprinted poster from August 19, 1853, advertising viewings of the head at the Stockton House for $1, pledges that it is “the veritable head of Joaquin Murrieta, the celebrated Bandit.”

Latta declares that there was always a “real” Joaquín Murrieta, that he did lead a gang of robbers, and that his primary business was stealing horses. Murrieta’s “horse gangs,” Latta concludes, cut a 200-mile 11-station route, La Vereda del Monte, through the Diablo Range based on water courses and traditional pathways, much of which still traces the contours of roads and creeks today. Latta carefully documents each station on the route, matching them up with landmarks he could identify in his travels in the 1970s. Some have disappeared — one corral was flooded to create Mississippi Lake in Henry Coe State Park, while an old adobe rancho and watering hole now lies directly under the San Luis Dam, which holds back the Pacheco Reservoir. Places along the route today carry names like “Murrieta Rocks” (a natural sandstone rock formation in a park near the Altamont Pass), “Joaquin’s Well” (a winery at the south edge of Livermore), and “Joaquin’s Rocks” (a rock spire near Coalinga).

On Google Maps you can see the hollowed out canyon of Cantua Creek, one mile west of I-5 in the rain-shadowed, treeless hills of the western San Joaquin Valley. In Ridge’s novel, a desperate skirmish takes place at the hideout in which Murieta at first escapes and then is chased down and shot. In Frank Latta’s historic treatment, the author concludes that Joaquín El Famoso never took part in the shootout at all. Latta speculates that the famous head belonged to Murrieta’s hostler. Latta says that Murrieta family members he interviewed in Sonora and California insist that Joaquín El Famoso returned to Cantua Creek after the shootout to help bury the dead, then was shot in a separate incident two days later in which he was not recognized. He died, Latta says, after finding refuge in an adobe house in Niles Canyon in present-day Fremont.

In the last few years conservationists have highlighted the Diablo Range, Murrieta’s rugged backdrop, as one of the highest-priority protection targets in the state. It is a unique place, they argue, not just for the state but in the world. Conservation analyses tend to focus on counts of species richness and biodiversity. They focus on the threats of sprawling new housing, of oil and gas exploration, of dams and power generation. They argue that the harsh, dusty spine of California is in a transition from a forgotten landscape to the centerpiece of the next half-century. They are working now to write and popularize this new story.

But the essential narrative of the inner coast ranges extends beyond the rare plants that evolved there. To understand land means to understand the people who lived and died on it. To understand the place of California today, you have to understand the place in the time of Joaquín Murrieta. That’s what John Rollin Ridge intended for us.

The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta, the Celebrated Bandit of California didn’t sell well in Ridge’s life. He died poor, possibly of tuberculosis, 13 years after the novel’s publication. In his own time, plagiarists robbed him of credit for the creation of the Joaquín Murieta legend. The celebrated bandit himself achieved only slightly more fame, eclipsed in the popular imagination by Zorro or Gregorio Cortez even though, as Frank Latta later wrote, “In the entire history of our Pacific Coast … no incident or epoch ever can compare in romantic interest with that of Joaquín Murrieta.” Tourists flocked to Los Angeles to visit the setting of the 1880s novel Ramona; the legend of Murrieta has inspired only scattered backcountry visitors like Heath Bartosh and his botanical mentors, to whom the story’s rugged western landscapes appeal. The California Department of Education provides a searchable database of books recommended for high school students, containing 2,551 titles. It is populated with Murieta’s East Coast contemporaries: Moby Dick (1851), The Scarlet Letter (1855), Walden (1854), Leaves of Grass (1855). A search for author last name “Ridge” yields nothing.

“Privilege is your history being history, and our history being electives,” says José González, the founder of Latino Outdoors and a partner at the Avarna Group. “It calls into question these questions of power, who sees themselves represented and why.”

González grew up in the central Mexican state of Nayarit and now travels the United States as a writer and consultant. He remembered “el bandido Robin Hood of the West,” as well as the corrido. “It’s an under-told story, especially outside of the Californio Chicano experience,” he wrote in an email. “The only reason I came across it was because of Chicano Studies.”

Gustavo Arellano, a feature writer who covers Mexican-American culture for The Los Angeles Times, says he remembers a high school teacher in Orange County giving him the book, no doubt in an attempt to remind Mexican American students they had a history of resistance in the state. But he remembers brushing it off. He later watched the Antonio Banderas movie Mask of Zorro with his mom, who told him Joaquín Murrieta was a Mexican hero. That’s where he started to think about a generational difference in how people reacted to the Murrieta story. “I’m Gen X, my generation was probably the first one to ever grow up not feeling ashamed of being Mexican,” Arellano said.

Older generations identified with Joaquín the resistance hero, Arellano says, but for younger Chicanos “it was just one of those tales of the past.”

Anyway, he continues, the novel skillfully taps into white fears of people of color rising up against past injustice, then validates that fear and soothes it. The rangers get Murrieta in the end. The freedom fighter’s head ends up pickled in a jar. Who needs that ending now? Arellano says the novel’s time has come — and gone. He compares Murieta to other relics of the past, like the myth of Ramona, the myth of the missions, the myth of the Gold Rush. Useful and perhaps essential studies in California history, and the way we got here, but nothing we need to surface. It reminded him of going looking for the old orange groves of Orange County: “It’s the old California you can’t even conceive of. It doesn’t really resonate with you.”

California is now the most populous, most diverse state in the union, with a gross domestic product the size of England’s. As its biracial State Senate speaker pro tem and its Mexican-American assembly speaker declared in 2016, after the election of Donald Trump, “California was not a part of this nation when its history began, but we are clearly now the keeper of its future.” In 2020 and 2021 Latinx students made up a plurality of the University of California’s admitted freshman undergraduates. The state is represented in the United States Senate by a Mexican-American mechanical engineer, and in the presidential cabinet by a Mexican-American graduate of the Stanford Law School.

“Why identify with Joaquín Murrieta?” Arellano says. “A hero like him is not going to resonate in California, because there’s no need. … the only people who could possibly connect to this are people who want to know about California history, and want to cheer on people who fought against colonizers.”

Arellano laughed when I asked if the book should be read in high schools. “You really think California is going to allow a novel about a guy who goes around killing white people?” he said. “That’s not going to happen.”

Yet others say that California has not so easily escaped its violent past. And even with more proportional representation in government, the culture the state elevates, from school curriculums to Hollywood, erases a lot of history.

“Joaquín Murieta is not just a foundational narrative of the state of California,” Hsu argues in The Paris Review. “It remains a vital novel today as racial profiling, deportations, criminalization, police violence, and racialized dispossession continue to devastate American communities in spite of putatively ‘color-blind’ laws.”

“Joaquín Murieta is a classic text. It’s an amazing text,” says Cal Poly literature professor José Navarro. “I think Joaquín Murieta is one of the few texts in the 19th century that stands the test of time.”

As we talked by Zoom, Navarro pulled out his own copy of the novel and read Ridge’s exhortation from the penultimate page:

Briefly and without ornament, the life and character of Joaquin Murieta have been sketched. His career was short, for he died in his twenty-second year; but, in the few years which were allowed him, he displayed qualities of mind and heart which marked him as an extraordinary man, and leaving his name impressed upon the early history of this State. He also leaves behind him the important lesson that there is nothing so dangerous in its consequences as injustice to individuals — whether it arises from prejudice of color or from any other source; that a wrong done to one man is a wrong to society and to the world.

Ridge depicts violence in a violent place that was a foundational time in the state’s history. His depictions of race and racism reflect the “complex and incoherent” views of its author, as Hsu wrote, in a country whose collective views on race remain complex and often incoherent.

“I don’t think curricula should specify specific texts (whether it’s Moby Dick, Leaves of Grass, The Narrative of Frederick Douglass, or Joaquín Murieta),” Hsu wrote in an email. “Because there are so many great works to choose from, I wouldn’t want to privilege some of them as required — but certainly Joaquín Murieta would be suitable for teaching in high school & undergraduate English classes, both because it’s a complex work of literature that critically represents its historical moment in a way that has been culturally influential and because its plot animates timely debates about racial identity, ethics, police power, and law.”

Ramon Saldívar, a professor of Chicano literature at Stanford who has called Ridge’s contemporary Walt Whitman his favorite American poet, agreed that Joaquín Murieta is suitable for students. The caveat, he said, is that you need a teacher to be able to teach it. You need someone capable of contextualizing the story, of navigating the violence, and of bringing home the lessons.

“You have to have teachers who know something about it, and are willing to present it on par with the history of American transcendentalism in New England,” he said. “And that’s not how they were taught. All of those old disciplinary boundaries and decisions made 100 years ago are still functional.”

Saldívar recalled first encountering the Murieta story as a graduate student at Yale. He was among the earliest students of Chicano literature, at a time when there was very little in the way of a formal curriculum. Scholars then were just starting to talk about what it even meant to call something Chicano literature, and how it fit into American literature, and Saldívar remembers first starting to think about what novels he would teach. He became interested in Chicano stories of resistance to racial injustice, and wondered how far back those stories went. The answer, in Joaquín Murieta, is in literally the first American novel featuring a Mexican-American main character.

In The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta, John Rollin Ridge tried to center an authentic version of California, and the harsh landscapes and damaged people that defined the early days of its statehood, in the literary canon of an East Coast-centric country. “I sit down to write somewhat concerning the life and character of Joaquín Murieta, a man as remarkable in the annals of crime as any of the renowned robbers of the Old or New World, who have preceded him,” Ridge begins the novel. “I do this, not for the purpose of ministering to any depraved taste for the dark and horrible in human action, but rather to contribute my mite to those materials out of which the early history of California shall one day be composed.”

You might conclude, as Hsuan does, that Ridge both succeeded and failed on an epic scale. The scale of Joaquín Murieta’s influence in cultural and academic works, even ones that don’t recognize they’re working from a legend created by John Rollin Ridge, is a testament to the enduring power of stories from the past to help us understand the present. Yet the invisibility of the novel, and of Ridge himself, in literary and academic canon shows just how difficult it is to challenge the stories white America tells about itself.

Joaquín Murieta, like John Rollin Ridge, arrived in California admiring Americans. Somewhere in the early days of statehood, the writer — and his protagonist — reconsidered. If the moral complexity Ridge captured sounds relevant today, then perhaps the story can be a field guide to the present. If the Diablo Range is the future of the state, if the state’s new push for ecological literacy means teaching Californian primary school students of the dusty hills where rivers run dry in the summer, then the celebrated Joaquín might also return to show us where we come from and where we are going.

“The character of this truly wonderful man was nothing more than a natural production of the social and moral condition of the country in which he lived, acting upon certain peculiar circumstances favorable to such a result,” Ridge writes early on. “Consequently, his individual history is a part of the most valuable history of the State. ”

Correction: This story has been updated with the correct location for Gustavo Arellano’s high school, which was in Orange County.

-237x300.jpg)