Every eight hours or so, the forecasters at the National Weather Service office in Monterey write up and publish a summary of what they see happening with the Bay Area’s weather. This bulletin, called the Area Forecast Discussion, goes into detail about various technical weather things like fronts and trough axes and cold air advection aloft as a consequence of retrograding shortwaves.

I read the Bay Area AFD with religious devotion three times a day (although I admit I still can’t explain a retrograding shortwave) because sometimes a line leaps out even to the lay reader. For example: the 3:05 a.m. update on October 4. At the time the various weather prediction models all showed some chance of real rain two weeks out, and the forecaster stuck a caveat on the computers with this phrase: “we’re fighting climatology.”

There is what weather we want, and what weather is supposed to be, and what weather happens. October in California is the month when those states conflict the most. Two weeks after the forecast showed a chance of rain, a hair-raising north wind started dozens of new fires. On October 13 California surpassed the driest point of the 2013-2015 drought and was the driest it had been in the 126-year observational record.

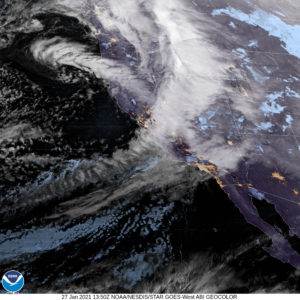

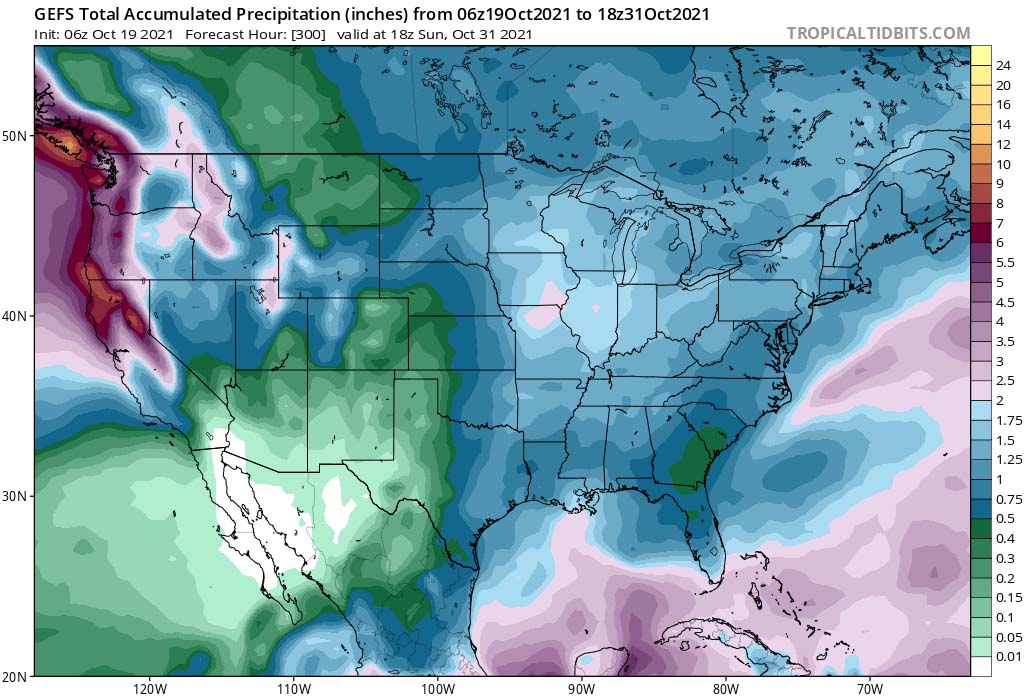

Now we’ve reached the middle of the month and there’s rain on the ground and in the forecast. This parched, tinderbox state desperately needs water. And so, like the forecaster, we can look at what the weather models show us might happen, and watch them match so closely with what we need and want to have happen. Before we assume it will happen, we can ask: where’s the conflict?

California, on statewide basis, is now experiencing its worst drought in observational record going back to late 1800s–narrowly beating out peak of last drought in 2014-15 (as measured by PDSI, a metric that takes into account both precip & temperature). #CAwx #CAfire #CAwater pic.twitter.com/PHgOZEUWgb

— Daniel Swain (@Weather_West) October 13, 2021

It rained 0.06 inches in the Bay Area in October 1980, my first experience of October rain. That would turn out to be a very dry October. San Francisco got 2 inches of rain in October 1981. Two-point-eight inches in 1982, a big El Niño year. It was drier in 1983, around a quarter of an inch. Very wet again in 1984, with more than 2 inches. And so on and so on. The October rains varied, because that’s Bay Area fall climatology. But there was a caveat to those years, too: varied meant that sometimes it rained a little, and sometimes it rained a lot.

My first-born daughter had just learned to walk in 2013 when, for the first time in my life, it failed to rain any amount in San Francisco in the month of October. In the long-term record, October rain shutouts aren’t unusual in the Bay Area, according to rainfall records kept by Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather Services. Going back to 1849, San Francisco has had 26 Octobers with 0.05 inches of rain or less. Fourteen of those were completely dry, zero-point-zero. We’ve also had 26 Octobers with more than 2 inches. October’s a volatile month when you study it over nearly two centuries.

But in the 33 years from the time I was born to the time my daughter was born, a whole lot happened in my life while in the background the Bay Area saw variable but always some-degree-of-wet Octobers. Nature was imprinting on me the idea of October rain.

It hasn’t been that way recently. At the start of the month, after reading that Area Forecast Discussion, I looked up the records for recent October rain in San Francisco: 0.0 in 2013, 0.0 in 2015, 0.01 in 2019, 0.01 in 2020. (Nearby SFO, and a lot of other places around the Bay Area, didn’t even get those hundredths.) Of course I can look at the long-term dataset and tell you that a very or even fully dry October in San Francisco is pretty normal. I find, though, that all my instincts declare that a normal October means a chance of rain. You can’t live the first 30 years of your life with something and then just abandon it easily. Clearly, I too am fighting climatology.

Statistically, October rain does not count much toward Northern California’s annual rainfall. In a region that averages 20-40 inches of rain a year, even a very wet October might only be 10 percent of the total amount. But October is a month that plays an outsize role in determining the character of a year.

“It pretty much dictates the end of fire season, or not,” says Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA and The Nature Conservancy who runs the California weather blog Weather West. “The end of agricultural watering season, or not. The growing season for vegetation as well.”

In a perspective piece for the American Geophysical Union in February, Swain wrote that drier and warmer falls extend fire season into the peak of offshore wind season, exacerbating a wildfire situation that seems to have become an every-year crisis in the absence of significant October rain. Climate models have long projected drier falls in California; now the observational record from recent decades backs them up. In every region in California, Swain says, rain is arriving later in the season.

“No one’s done the formal study to say, ‘Is this particular dry autumn due to climate change,’” Swain says. “It would be a tall order at this point. The signal to noise ratio wouldn’t be strong enough to be super convincing. But reading between the lines, there’s really strong evidence we’re seeing a later onset to rainy season in California at this point. That’s true everywhere. All these parts of California seeing a later onset to rainy season. Check. It’s in the data.”

I remember, in October 1991, driving home from a soccer game and seeing the smoke coming up from the East Bay Hills at the start of the Oakland Hills Fire. I remember displaced friends coming to stay with us and not knowing for three days whether their house had survived the fire. I realize as a parent now how little I understood then of their anxiety. But I also remember that fire because it was such an anomaly. At the time, as a not-super-aware 11-year-old, it felt like a one-off catastrophe. In some ways that was true: the Oakland Hills Fire remained the worst fire disaster in California history for nearly three decades.

A few days ago I went and looked at the weather record for October 1991. The fire started on October 19. It hadn’t rained yet that month, and ferocious Diablo winds fanned the fire and spread it rapidly into dry vegetation in the hills. What’s amazing, at least to my sensibility after the last few years, is what happened next. The winds flagged on October 22. Firefighters declared the fire under control on October 23, four days after it had ignited. On October 25, a storm moved in. On October 26 it poured. By October 27 well more than 2 inches of rain had fallen and the California fire season had ended.

Compare that to October fire weather in the last four years:

-The Tubbs Fire started on October 8, 2017 in a hot dry wind and tore quickly through the suburbs in nearby Santa Rosa. Four days after the fire had started, with the dry wind still blowing, firefighters evacuated Calistoga. The Tubbs surpassed the Oakland Hills Fire as the most damaging in California history. The season’s first paltry rain, about a third of an inch most places in the Bay Area, arrived on October 20, but it wasn’t enough. The fire was declared contained on October 31. A dry start to November meant Bay Area fire season didn’t end until Thanksgiving.

-The Camp Fire started outside Paradise on November 8, 2018, not even an October event, but one possible because it had been a below-average dry October and unusually dry start to November. The new most destructive fire in California history burned for 16 days until, finally, the rainy season arrived.

-The Kincade Fire started on October 23, 2019. The fire burned for four days, then the dry wind kicked up again and blew the fire into the town of Windsor. The Kincade Fire kept burning for two anxious weeks before firefighters controlled it. Even after it was declared contained in early November, the Bay Area didn’t record its first 2 inches of rain for another month, until mid-December.

-The August Complex, California’s first million-acre fire, started in August 2020 but just kept burning through September and October because even in far Northern California it didn’t rain much either month. In the Bay Area, where October was nearly or fully dry, the skies stayed smoky through Halloween. Firefighters declared the August Complex controlled in mid-November.

This is the Bay Area’s new October climatology. Over the last decade, the average hottest day of the year in San Francisco has shifted from late September to early October. The average arrival of fire-season-ending rain has shifted from early November to mid-November. These changes were quite accurately predicted decades ago, and yet knowledge has not diminished the frustration of living them. It is still difficult to arrive on October 1, and expect rain to come soon, and see none in the forecast. It is difficult to understand that the climatology we’re fighting is new.

“It used to be, some years would have wet autumns, some years would have dry autumns,” Swain told me. “Wet autumns you didn’t have to worry about fires, dry you did. But having every autumn be a potentially severe fire year is not typical. Usually there would be years where you’d have very little fire risk because it was raining. And that’s not happening.”

The rain means so much more this year. Severe drought has killed or stressed millions of trees. Those trees are standing so very much like matchsticks across the Western United States. It is hard not to see the withered leaves and the hillsides turning sickly orange. The dirt on the trail has become like chalk dust. In open spaces around the Bay Area, in the next month either rain will arrive, or fire will.

It seems to be our good fortune that this October will be the one when storms break through the climatology. But hoping you get lucky isn’t much of a strategy, and climate change increasingly makes good luck less likely. Mostly because of how warm it has become, Swain says, California is becoming a more arid place. Arid is a constitutional affliction, not a temporary illness. Californians live in more of a desert now than we did 20 years ago.

“It’s clear what’s going on, and even more importantly, even if this trend stalls for a while, it’s going to resume in the same direction,” Swain says.

A problem, Swain says, is that the climate models correctly predicted the amount of warming our emissions would cause, but people have dramatically underestimated the consequences of that warming. Scientists who study extreme events have long warned that “reality would be worse than the formal predictions,” he says.

It should be a caution. The earth is warming as forecast; the ramifications of that warming have been far worse than forecast. The current costs of climate change in California — moving people and infrastructure out of fire zones, moving people and infrastructure away from the coastlines, smoke days, fire days, lost agricultural productivity — are incomprehensible. But the effort to reduce those costs, like breakthrough October rain, is fighting a very persistent background pattern of inactivity. Swain says he increasingly likens it to a train accelerating down a runaway track. The farther it gets, the worse it gets. The brakes still work fine! But the engineer is choosing not to use them.

“Unless you actively do something about it the train is not going to stop and keep going downhill and accelerate and eventually fly off the tracks,” he says. “The train is still on the tracks, but do we choose to apply those brakes or not? Prudence would have dictated we do that a long time ago.”

There’s a branch of natural history called phenology, which is all about the study of how life interacts with time and the seasons. Any gardener who thinks about day length or chilling hours is a student of phenology. Scientists who study bird migrations are studying phenology. A deeply informed phenology lies at the heart of traditional ecological knowledge.

Phenology is about how plants and animals harmonize climatology. But as has happened in most mass-extinction events in the past, the climate is changing faster than many plants and animals can adjust. Phenology is also about who’s fighting climatology, and how they’re faring.

One California symbol of fighting and losing might be the monarch butterfly. In 2018, as the monarch’s numbers were already crashing from habitat loss and pesticides, Northern California had a false-spring heatwave in mid-February. The monarchs, confused by the weather cues, left their protected overwintering groves to start on their long-distance migration. They flew into a trap. Two weeks later winter returned. Cold storms seem to have destroyed the tens of thousands of butterflies who left the groves early, hastening the western migratory population on its way to extinction. They were unlucky.

What is our weather supposed to be in October? I have never had to pay close attention to October rain because for so much of my life it just arrived. Then suddenly the faucet turned off. Swain called the new fall wildfire regime a step change, like you’re on a flat step and suddenly you vault up to the next level. Many more Californians are paying attention to the weather now, but we’re not yet backing down the stairs. October is becoming hotter and drier, as the climate models have always said it would if we kept emitting greenhouse gases. Autumn drought, and all-season heat, are our new climatology. Even with October rain returning this year, we face all sorts of severe drought trouble this winter. We don’t want to be the monarchs, rejoicing too early and then caught out away from safety when the storm comes.

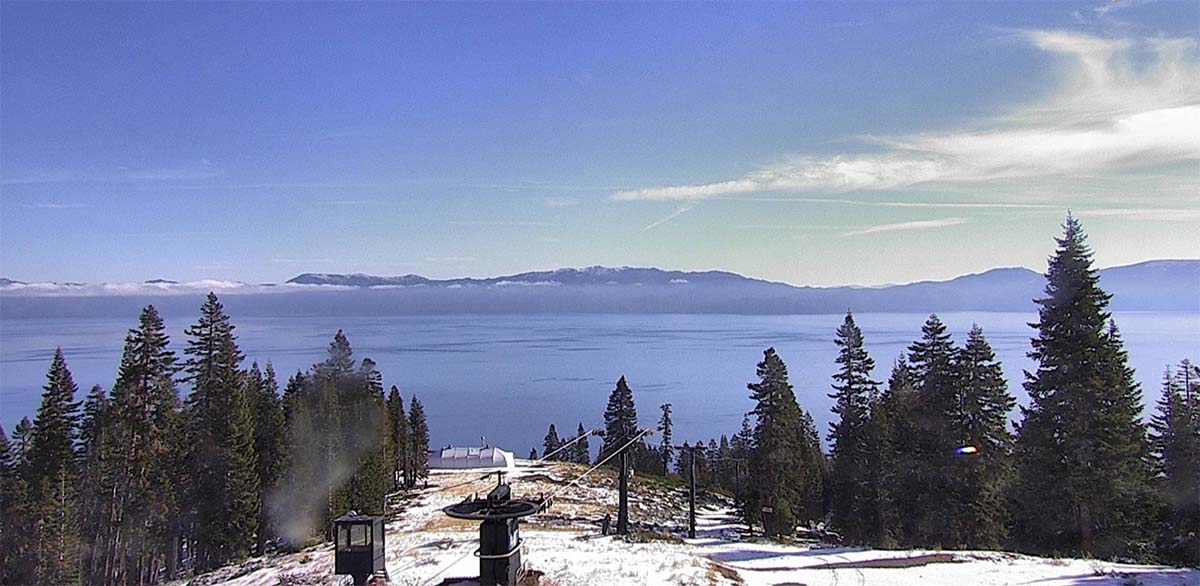

Nonetheless, from the view of October past, this rain is normal. It is what my instinct, my California human phenology, tells me is right. There is joy to this week: an old friend has returned, albeit one tinged with betrayal: you weren’t there when we needed you. And I find, as the raindrops hit the window and pavement smells of fresh rain, an odd kind of nostalgic melancholy. As a devoted reader of technical forecast bulletins, I realize that this week we are the beneficiaries of an increasingly lucky turn: the past has won a fight over the present.